9/2025 Retelling my ‘Ambomaan pakana’ heritage

My quest to understand my cultural heritage started as a research project for my undergraduate studies. I explored the precolonial costumes of the Aawambo people due to my curiosity to find out what they were wearing prior to the striped cloth ondhelela dresses. I discovered that the Finnish missionaries were an influential cultural agent of the contemporary dress; some ornamental artifacts were collected during their activities and stored in Finnish archives. I vividly remembered a conversation with my supervisor then, about how I would one day plan to visit Finland to view these intriguing Aawambo cultural belongings.

In 2022 and 2025 I found myself excited yet anxiously embarking on trips to my once anticipated destination, Finland. For both trips I have been staying at the Villa Hortus, located next to the University of Turku, which was a blessing in disguise as this made my daily movements manageable. The language barrier was not challenging as everyone in the city communicated well in English. The only Finnish word I have mastered to remember was ‘moi’ which translated to a greeting. The city reflected a refreshing ambience due its green scenery decorated by rivers. Apart from the forestry scenery, the city displayed various antique buildings amidst the modern structures.

Hiking and collecting blueberries and mushrooms become a frequent yet memorable activity to do during the weekend. Other adventures included traveling for the first time with the Tallink ferry from Helsinki to Estonia. I didn’t bring along any Namibian edibles and therefore Finnish karjalanpiirakka (Karelian pie) and chocolate covered liquorice sweets became my weekly treat. During my daily walks around the city the notorious Turku Cathedral which faithfully rang its bell everyday, was a constant reminder for the reason I had travelled.

Namibia and Finland have an intricate relation brought by the Finnish missionaries who established the first missions among the Aawambo people in northern Namibia in 1870. The first mission stations were established in Ondonga, Uukwambi, Ongandjera and Uukwanyama. One often ponders about their experiences which required them to leave behind a life different from the cold weathered and forest environment. How did they manage to endure a baking hot and dry country with a contrasting culture and language? Why did they want to teach people about the bible according to their Eurocentric standards? What was their interpretations when they saw the clothing and lifestyle of the encountered communities.

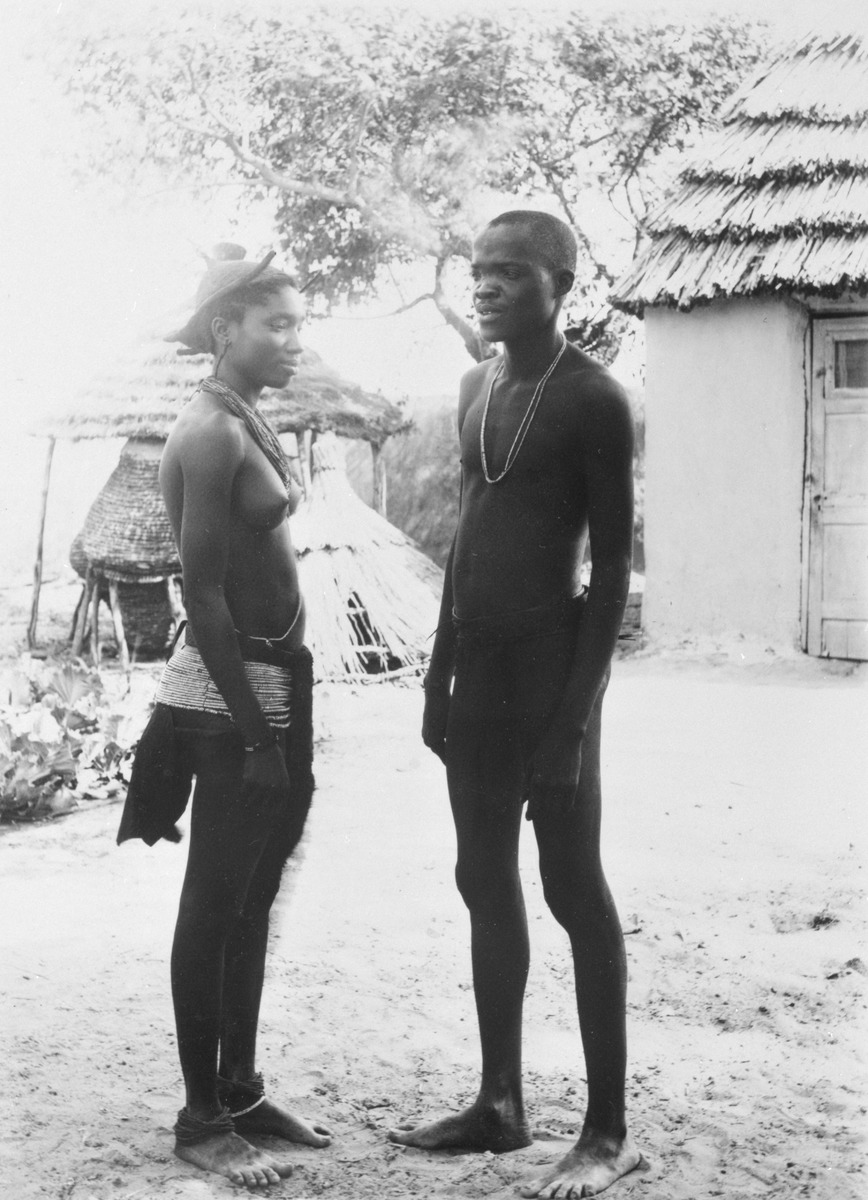

My fashion and textile background has influenced me to interrogate the impact of missionisation on clothing, by identifying differences in elements worn during different periods. Early photographs of Aawambo people have always mesmerized me. During my first trip in 2022, I got a chance to explore the photographic archives at the Finnish Heritage Agency in Helsinki. The Finnish mission workers were rigorous in documenting heterogeneous aspects of their journey, creating alluring yet sometimes disparaging imagery of Africa. Some of the images I analysed were captured by missionaries like August Pettinen and Hannu Haahti. Viewing the collection stirred intense emotions of fascination and disappointment. I noticed the reoccurring Finnish words Ambomaa: pakanoita which was handwritten on the descriptions behind. The words translated to ‘Ovamboland: pagans’ were used to describe the unconverted Aawambo by the missionaries.

Image 1: An example of Aawambo precolonial attires. Picture by August Pettinen, 1893–1896. Source: Finnish Heritage Agency

In some images, the ‘pagan’ Aawambo wore leathery attires with ornaments crafted from the local environment complemented by distinctive hair-dresses. The lack of cultural tolerance and appreciation made the missionaries overlook the meanings embedded in the adornments. I often had to inquire further into the images as some might have been staged to reflect the photographers’ Eurocentric perception of ‘pagans’. The transformed women dressed in sombre long dresses accessorized with aprons while men wore trousers and shirts, which were the Eurocentric clothing donated to converts. Both wore shaven heads or covered with head wrap, a daunting hairstyle which expressed a stripped off identity. According to my observation, the images with the converted Aawambo reflected natural postures and were taken with ease. The ‘pagan’ Aawambo seemed posed to portray their disregarded clothing or practised cultural activities. In image 2, the converted Aawambo were centred in the image while the group of ‘pagan’ children are positioned on the side like props.

Image 2: Missionary celebration (41st anniversary) in Oniipa, Southwest Africa. Picture: Hannu Haahti, 9.7.1911. Source: Finnish Heritage Agency.

According to some interviewed informants, the missionaries forced converts to discard or burn their ornaments to portray their transition from the pagan lifestyle to Christianity. Interestingly, the derogated cultural objects were collected by the missionaries and shipped to Finland. Some missionaries have documented that their collected artefacts were gifted by the locals, royal families or through bartering. These objects were exhibited to the Finnish audience to view as evidence of the evangelical work. During my trip in 2025, I was given the opportunity to engage the Martti Rautanen’ collection at the National Museum in Helsinki which is the largest in Finland. The collection accumulated by Karl Emil Liljebald are currently stored at the University of Oulu. Both collectors were early missionaries who conducted mission work among the Aawambo.

The objects I selected were connected to basketry, leather and metalwork, to support my investigation regarding the evolution of cultural craftsmanship and symbolic attachments. The Liljebald collection has samples of coiffures which left many disturbing questions across my mind. How were the hairpieces for example collected and on what basis was it given? Hair is not an appropriate object to present to others as it forms part of a person’s existence. It’s important for one to appreciate and tolerate cultural diversity and expression to avoid disrespecting the encountered societies and their culture. Fortunately, some provenance research has been conducted on Rautanen’s collection to inform and preserve the knowledge and oral tradition related to each cultural object.

More Namibian scholars including myself have jumped on the bandwagon to conduct additional provenance research from the affiliated communities. For my doctoral studies I am investigating the existent symbolic connotations embedded in uuputu (metal beads) among the Aawambo people, to determine whether the production and usage was diminished through the adoption of Eurocentric cultures. I choose to retell my heritage to further share and preserve the existing or newly reclaimed cultural narratives, traditions, and histories for contemporary and emerging generations.

Loini Iizyenda, PhD student and lecturer in Fashion and Textile Studies, Sustainable Design, University of Namibia

Iizyenda, Loini (2019). The Impact of Finnish Missionaries on Traditional Aawambo Dress. In Marjo Kaartinen, Leila Koivunen and Napandulwe Shiweda (Eds.), Intertwined Histories: 150 Years of Finnish-Namibian Relations. University of Turku.

Iizyenda, Loini (2024). Narratives of Uuputu Artefacts: An Intrusion of Finnish Missionaries on the Cultural and Technological Development of the Aawambo People. In Raita Merivirta and Leila Koivunen (Eds.), Colonial Aspects of Finnish-Namibian Relations, 1870–1990: Cultural Change, Endurance and Resistance (pp. 154–168). Finnish Literature Society. doi:16971622.13