Insect herbivory in forest ecosystems

At the global scale, the larger part of plant damage is due to insects—the ‘little things that run the World’. Usually, we recognize the impacts of insects on ecosystems only when the insects eat away plant foliage completely or almost completely. However, this happens only during a population eruption (an outbreak) of some insect species. In actuality, it is nearly impossible to find a mature native plant that bears no marks of insect feeding. Background herbivory (also known as endemic or nominal herbivory) refers to the ‘minor’ losses of plant biomass that occur when herbivore densities are at the ‘normal’ level for the given ecosystem (in contrast to ‘major’ losses during outbreaks). Current theories predict that the proportion of plant biomass lost to insects (currently, on average, 5% across the globe) will increase as the climate warms, but the supporting evidence is based primarily on outbreaks of economically important pests.

Research methodology

We explore the impacts of background herbivory on the structure and functions of forest ecosystems using a combination of the following approaches:

- assessment of plant damage by insects along environmental gradients and across different communities

- experimental studies of the impacts of low levels of insect herbivory on plant growth and fitness

- experimental studies of the impacts of climate warming and previous plant damage on herbivory

- research synthesis of the existing knowledge, including meta-analysis

- ecosystem modelling.

Background herbivory is detrimental: effects on tree growth

The annual removal of 2–16% of the leaf area by punching holes in leaves of mountain birch saplings over a seven-year period resulted in a pronounced 30–78% reduction in sapling growth. Thus, the predicted increase in background herbivory due to climate warming would be expected to have previously unrecognised adverse effects on tree growth. Ecosystem modelling confirmed that, in the long term, background herbivory is likely to have stronger effects on boreal forests than will short-term devastating outbreaks of defoliators. Thus, the development of plant evolutionary adaptations to herbivory is more likely to occur in response to background damage, which permanently acts on plants, than to severe but episodic bouts of damage. Our current studies focus on the variations among tree species in their responses to realistic increases in background herbivory in subarctic and south taiga forests.

Background herbivory in climatic gradients

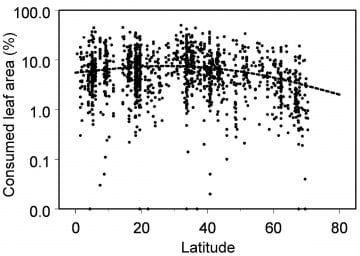

Since 2004, we have been conducting annual measurements of the damage to white and downy birches, Scots pine and Norway spruce by leaf-chewing, leaf-mining, sap-feeding and gall-forming insects along latitudinal gradients in Northern Europe. Beginning in 2015, we also started to evaluate the densities of root-feeding insects and to estimate root losses to these insects. In 2009, we arranged to collect data on damage to trees by insects across the globe. These data, in combination with published information, demonstrated a peak in the background losses of woody plant foliage to insects in temperate zones, a slight decrease towards the equator and a strong decrease towards the poles. We are currently exploring the distribution of foliar damage to woody plants along altitudinal gradients, and we are searching for global patterns in root damage due to insects.

(after Kozlov et al. 2015)

Past changes in background insect herbivory

Climate warming is in progress: the recent mean global temperature is about 0.5–0.6 °C higher than it was in mid-1970s. Experiments on temperature elevation and studies of herbivory in climatic gradients both have predicted that the rise in ambient temperature will be accompanied by increases in plant damage by insects. However, contrary to these predictions, our analysis of the published data demonstrated that foliar losses of woody plants to insects did not change from 1952 to 2013 within the temperate climate zone and, in fact, significantly decreased in the tropics. Similarly, none of willow-feeding leaf beetle species, which we monitored from 1993–2014 in subarctic forests, have shown any increased abundance over the past 20 years, even though spring and fall temperatures in our study area increased by 2.5–3 °C. We are currently analysing temporal trends in insect damage to birch trees using original data collected from 1981–2016, and we are exploring factors that affect the temporal stability of the background herbivory in natural ecosystems.

Distribution of insect damage among plant species and among ontogenetic stages

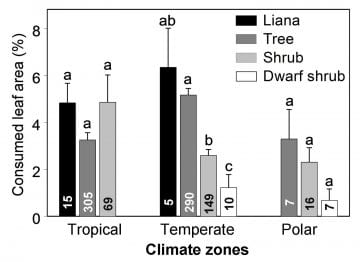

The levels of background losses of woody plant foliage to insects differ between plant functional types, and the relationships of foliar losses to plant functional traits and ecological strategies vary depending on the climate zone. We found that large trees and fast-growing species generally suffer greater foliar losses to insects when compared to small dwarf shrubs and slow-growing species. Similarly, we found that juvenile birches suffer less insect damage than is observed in mature trees, but this is due to the lower apparency of the young trees and not to better defences. We are currently determining whether the geographical variations in damage observed in juvenile trees follows the pattern we identified in mature trees.

Human impacts on insect herbivory: pollution and urbanisation

The effects of pollution on biota are generally detrimental. Nevertheless, a meta-analysis demonstrated that industrial pollution favours plant-eating insects, although this effect may not be as strong as once believed. We found that the positive effects of pollution on herbivorous insects increased with increases in both summer temperature and precipitation. In contrast, although the mean temperatures in cities are higher than in rural habitats, tree damage by free-living defoliators and leaf miners was 16.5% lower in urban than in rural habitats. This effect was significant in large cities (city population 1–5 million) but not significant in medium-sized and small towns. We are currently exploring the mechanisms underlying the adverse effects of urbanization on background insect herbivory.