The Finnish Medical Mission in Owambo and Kavango, 1900–2010

Kalle Kananoja

Finnish missionaries played a leading role in the development of healthcare in today’s northern Namibia until the independence of the country in 1990. During South African colonial rule, Finns were for a long period practically the only people to practice biomedicine among the Aawambo. As elsewhere in colonial Africa, medical practices were socially and politically contested in South West Africa. Missionary medicine not only shaped healthcare, but also the identities and cultural practices of the Aawambo.

The Finnish medical mission gradually took a political role in the ideological contest between South Africa’s apartheid regime and the Swapo resistance movement during the guerrilla war (1966–1988). Warfare and healthcare became intertwined with apartheid politics and aggression. Thus, the Finnish missionaries became politically conscious in the fight against South African oppression.

The Early Development of the Medical Mission

When the first missionaries arrived in Owambo, local concepts of illness differed from those held by the newcomers. Magical beliefs connected to illness, death and childbirth were vastly different to European concepts of health, and were not easily eradicated. Healthcare was an important part of missionary work, even before the arrival of the first trained medical doctors and the formal establishment of clinics and hospitals. Despite their rudimentary medical skills, the reputation of missionaries as healers spread widely among the people. These early activities undermined the authority of traditional Ovambo healers and also helped establish trust between the Ovambo and the missionaries.

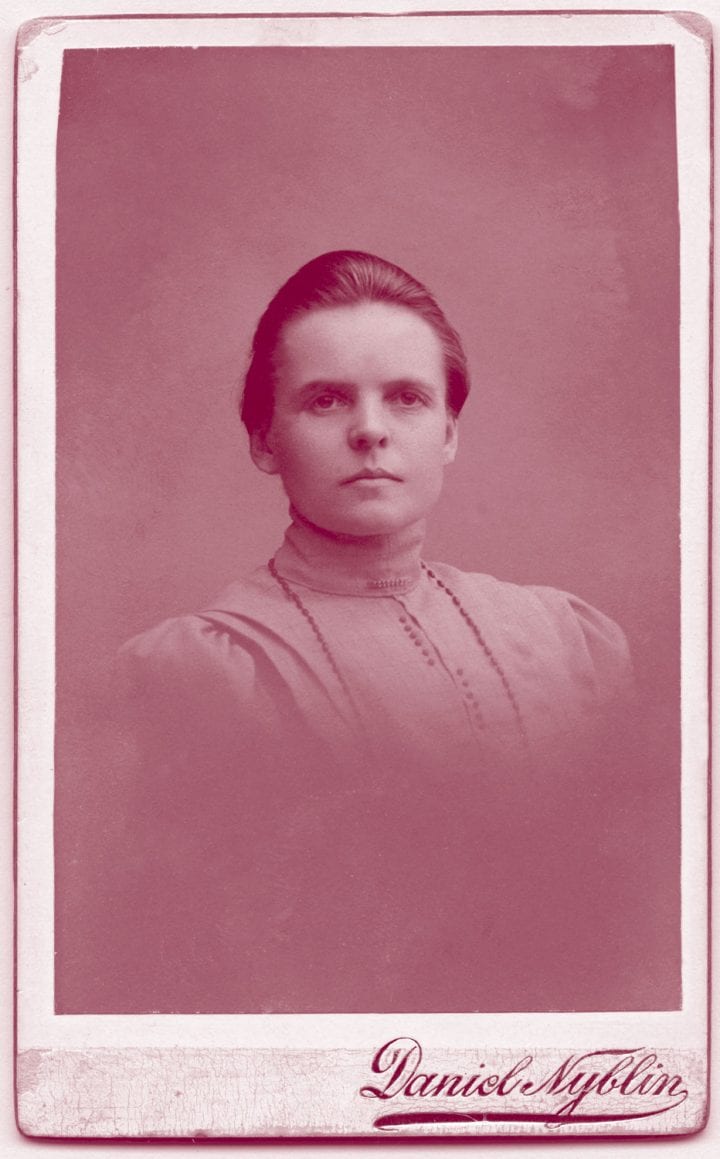

Dr. Selma Rainio arrived in Owambo in December 1908 and settled in Oniipa. Rainio worked alone, meaning that in practice she also assumed the duties of a nurse and a pharmacist. A few years later, trained nurses began to arrive from Finland. Onandjokwe Hospital, constructed in Oniipa in 1910 and inaugurated on 9 July 1911, was gradually extended with both smaller and larger buildings for dwelling and healthcare purposes. Inpatients and their families stayed in huts erected for the purpose.

The provision of healthcare services was not only about medicine, but also about religious ambitions and proselytizing. Providing medicines that could heal attracted locals to the missionary hospital, where the missionaries soon approached them with their religious aims. This strategy succeeded in the long term. Even people who wanted to have little to do with missionaries in general could be approached by means of medical care.

Early missionary medicine often sought legitimation through grand displays of Western medical technology. Vaccination and surgery represented the most spectacular forms of specialized knowledge possessed by missionary doctors as they sought to cure African bodies. Medical work was suffused by the religious convictions of physicians and nurses, and educational endeavors formed a central part of the medical work of missionaries. This included the training of African auxiliaries to serve in mission hospitals.

Health training formed an integral part of the medical mission and was a matter of necessity, since only by training local people was it possible to satisfy the needs of the rapidly-expanding health services and to raise general standards of health. Schools made use of the Selma Rainio’s textbook on hygiene, written in Oshindonga. Health education and advice on cleanliness were offered to hospital patients. The first hospital workers were men, but women began to be employed later. The training of auxiliary nurses started at Onandjokwe in 1930. Educational standards were gradually raised as more textbooks began to be produced in Oshindonga. In 1961, the training school of auxiliary nurses was officially recognized by the South African Nursing Council. The official training of midwives began in 1965.

If the healing practised by the missionaries had already undermined traditional medicine, the arrival of doctors and nurses was even more significant. Many Ovambo leaders began to rely on the modern biomedicine offered in Onandjokwe Hospital. Sometimes patients had to stay for longer periods in the hospital, and were in constant contact with missionary proselytising. Yet, writing in the late 1960s, Dr. Hannu Kyrönseppä noted that traditional disease concepts still held sway among many patients, who did not have complete confidence in modern medical science.

The construction of Onandjokwe Hospital did not mean that healthcare ceased at other mission stations. Instead, medical services were still provided by missionaries at other stations as they had been before the arrival of Dr. Rainio. Missionaries often turned to her for advice, but continued to treat people with medicines and practices that were perhaps not completely up-to-date.

Medical help gradually expanded into other regions. Linda Helenius, a nurse, established a small out-patient clinic among the Kwanyama, in 1922. A little later, an in-patient hut with a couple of rooms was also constructed. Dr. Rainio performed her last years of service (1936–1938) in Engela, where the hospital then consisted of a two-room out-patient clinic, as well as eight huts for in-patients and four additional huts for patients who suffered from infectious diseases. In 1933, Helenius established another base for medical work in Eenhana, assisted by an Ovambo auxiliary nurse named Rakel Kapolo. In the 1930s, the clinic network also spread to western Owambo, where Nakayake Hospital was established in Ombalantu. Medical services in Owambo expanded even further in the 1950s. Due to a shortage of medical doctors, clinics were usually run by nurses.

Selma Rainio as photographed by Daniel Nyblin’s Atelier (ca. 1900–1920). The Finnish Heritage Agency.

Medical Work in Kavango

The Finnish Missionary Society began its work in the Kavango River region in the 1920s with the establishment of a mission station in Nkurenkuru. Finns began medical work in Kavango in 1951, when a nurse was placed at the mission station of Mpungu on the western border of Kavango. The first Finnish doctor, Anni Melander, arrived in Kavango in 1952, when she moved from Onandjokwe to Nkurenkuru. Two or three Finnish nurses had also worked in the State Hospital of Rundu in Kavango since 1953. The Royal Catholic Mission was also active in Kavango and competed with the Finns in the provision of healthcare services. There were several Catholic mission hospitals in the area. In addition, the Dutch Reformed Mission was working in Maseru from the early 1960s.

After Melander’s death in 1957, medical work in Kavango was led by Dr. Håkan Hellberg, who wrote a lively memoir of his work in the region, and whose spouse Marita served as a nurse. When they arrived in Nkurenkuru, the clinic officially offered fifty hospital beds, but in reality they only had three actual beds. Most patients slept on a mat on the floor. The number of in-patients was often between 40 and 60, although Dr. Hellberg sometimes found it difficult to differentiate between patients and their family members who stayed in the hospital. A substantial number of patients came from the Angolan side of the border, sometimes speaking languages that were barely understood by the Kwangali-speakers in Nkurenkuru.

Healthcare under South African Rule

After the First World War, South West Africa was administered by the Union of South Africa. South African healthcare practices were discriminatory and led to a deterioration in the health of the local black population. As elsewhere in colonial Africa, the South African medical administration primarily strove to sustain the labor supply of black people and to protect the health of the whites. This led to the low quality or total absence of healthcare infrastructure, such as hospitals. The medical staff stationed in the north were there to handle the recruitment of men for labor contracts, conducting examinations and giving immunizations. Missionary societies were left to provide healthcare to local people.

Onandjokwe Hospital continued to offer curative treatment and primary care. Patients commonly suffered from malaria, venereal diseases, influenza, leprosy and various injuries. Malaria was rampant during the heavy seasonal rains. Vaccination campaigns against smallpox, the plague, diphtheria and poliomyelitis were carried out in the 1940s and 1950s. In 1958, a fire in Onandjokwe Hospital destroyed huts and other buildings. These were replaced with modern inpatient wards, a maternity ward and a clinic, as well as a ward for infectious diseases and a tuberculosis ward.

Healthcare services continued to expand elsewhere in Owambo. In the 1960s, there were 28 clinics and small hospitals throughout Owambo. South Africa subsidised the Finnish medical mission irregularly and insufficiently from the 1930s, making a small contribution in relation to the number of people living in Owambo.

In Owambo, the first government hospital was only opened in 1966 in Oshakati. Designed according to the ideology of the apartheid regime, white patients were offered a higher standard of care than blacks. Furthermore, white and black staff were accommodated separately and not allowed to socialize outside work hours. Finnish nurses found this intolerable and gave in their notices quite quickly, and also refused to register as white nurses.

The Finnish missionaries’ view of South Africans and apartheid were divided between criticism and acceptance. In the 1960s, the missionaries generally kept a low profile regarding apartheid as South Africa funded the medical mission and could control the missionaries’ presence in the region by refusing to issue visas. The South African government depended on the medical mission’s contribution to healthcare in Owambo, yet it was afraid that the missionaries would meddle in political issues. At the same time, OPO/SWAPO accused missionaries of being against the liberation movement.

Altogether, health services were extremely fragmented under South African rule, and varied in quality and accessibility in different areas. Finnish missionaries gained the trust of local leaders and the liberation movement, and openly began to support SWAPO’s aims from the early 1970s. This strained relations with South Africans, who labeled the Onandjokwe Hospital “a terrorist hospital,” as Catharina Nord has shown. The hospital received patients who had been involved in war-related incidents, and suffered from injuries caused by landmine explosions or shootings. However, nothing indicates that Onandjokwe Hospital was part of a warfare organization, and although wounded soldiers came for help, the hospital mainly cared for civilian patients.

The Finnish Medical Mission’s Legacy in Independent Namibia

With the independence of Namibia in 1990, the new government had to remodel and reorganize the apartheid healthcare system. Superfluous hospitals were closed down and others were renovated and refurbished in order to modernize existing services. Many of these, especially in Owambo, were old missionary hospitals or clinics. The Finnish government financed the total replacement of Engela Hospital. The goal was to provide access to all Namibians within a 3-hour walking distance. High priority was put on maternal and child healthcare provision.

Onandjokwe Hospital, now run by the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Namibia, was renovated and celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2011. As reported by the Finnish Medical Journal, the hospital has suffered from a lack of resources, including staff. The number of Namibian medical doctors in Onandjokwe, as well as in other public hospitals, has remained low. The hospital has focused on improving the conditions for HIV-positive mothers. Another Finnish project has focused on eye diseases and eye disorders and the provision of affordable glasses for patients.

Bibliography

Halmetoja, H., Lähetyslääkäri Selma Rainio länsimaisen kulttuurin ja lääketieteen edustajana Ambomaalla vuosina 1908–1938. Unpublished MA thesis, University of Joensuu, 2008.

Hellberg, H., Doktor i Kavango. Helsingfors: Fontana Media, 2006.

Kyrönseppä, H., Sixty Years of The Finnish Medical Mission. Oomvula omilongo hamano dhEtumo lyuunamiti lyaSoomi. Helsinki: Finnish Missionary Society, 1969.

Kärki, J., Länsimainen terveydenhuolto Lounais-Afrikassa vuosina 1920–1939. Unpublished MA thesis, University of Joensuu, 2007.

Landau, P., Explaining Surgical Evangelism in Colonial Southern Africa: Teeth, Pain and Faith. Journal of African History 37, 1996, 261–281.

Miettinen, K., On the Way to Whiteness: Christianization, Conflict and Change in Colonial Ovamboland, 1910–1965. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2005.

Nord, C., Healthcare and Warfare: Medical Space, Mission and Apartheid in Twentieth-Century Northern Namibia. Medical History 58, 2014, 422–446.

Notkola, V., H. Siiskonen, Fertility, Mortality and Migration in Subsaharan Africa: The Case of Ovamboland in North Namibia, 1925–90. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2000.

Peltola, M., Suomen Lähetysseuran Afrikan työn historia. Helsinki: Suomen Lähetysseura, 1958.

Wallace, M., Health, Power and Politics in Windhoek, Namibia, 1915–1945. Basel: P. Schlettwein, 2002.

About the Author

Dr. Kalle Kananoja is an independent scholar working at the intersection of medical ethics and patient activism.