A Joint Effort: Owambo Agency in the Karl Emil Liljeblad Collection

Kaisa Harju

The Karl Emil Liljeblad Collection is the second largest collection of Aawambo material culture in Finland. It contains over 700 objects and “natural samples” from Northern Namibia (formerly known as Owambo). Approximately 400 objects and 225 natural samples were amassed by the missionary Karl Emil Liljeblad (1876–1937) during his missions to Africa between 1900–1907 and 1912–1919 and his ethnographic field trip to Owambo between 1930–1932. The collection embodies different aspects of the everyday life of the Aawambo. It includes containers and dishes made from palm leaf, wood and calabash, as well as jewelry, hair pieces, amulets and belts for healing and protection, healer and diviner instruments, weapons, wands, agricultural implements, musical instruments, tobacco containers and wooden sculptures.

The collection is closely linked to the life of Emil Liljeblad. However, it should be seen as a product of common effort, since many people took part in its formation. After Liljeblad’s death, his eldest daughter, Aune Liljeblad (1905–1990), organized the collection. She also supplemented it with sixty-two artefacts and two natural samples, as well as writing the main catalog that contained information on objects. She eventually donated the collection to the University of Oulu. What is more, the collection was coproduced by the Aawambo. Its content was determined by status and the personal interest of Liljeblad, but also by the motives and customs of the Aawambo who decided (or in the case of spiritual objects might have been obligated to) to donate or sell their objects to Liljeblad – or withdraw certain artefacts from exchange.

This text will map the role of the Aawambo people in the Liljeblad Collection. The obvious challenge with this task is that Liljeblad wrote little about his collecting activities. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, ethnographic collecting was considered a mundane part of colonial life and was rarely mentioned in letters or diaries. Even those who had a more scientific grasp of ethnography often saw objects mainly as a self-evident proof of cultural traits and were seldom interested in writing down the histories of individual objects. We simply do not know to whom each object in the Liljeblad Collection previously belonged or when or from which Owambo kingdom they were collected. Still, the collection itself provides physical proof of local agency. By looking at the content of the collection – what kind of objects it contains – and by comparing it to the fragmented historical evidence and previous research on collecting and Aawambo culture, it is possible to draw some general conclusions on how Aawambo people participated in the formation of the collection.

Traders, Friends and Converts

Liljeblad arrived in Owambo for the first time in 1900 as a missionary of the Lutheran Finnish Missionary Society (FMS). He was not the only Finnish missionary, nor the first to collect Aawambo objects from northern Namibia. Finns had amassed local artefacts – some just a few souvenirs and some formidable collections – since the beginning of the Finnish Owambo Mission in 1870. What is particular about Liljeblad as a collector, however, is that he seemingly brought more Aawambo objects to Finland than any other individual missionary. Second, most of the objects in the Liljeblad Collection were gathered on his ethnographic field trip of 1930–1932, which was one of its kind in the context of the Finnish Owambo Mission.

One explanation as to why Liljeblad obtained fewer objects during his fifteen years as a missionary than his two years as a researcher might be that he was simply less active as a collector prior the 1930s. It was relatively easy for Finnish missionaries to obtain certain local objects even when they were not systematically amassing a collection. Exchanging material goods with local communities was an integral part of gaining more of a foothold for the Owambo Mission. Missionaries understood trading and reciprocal gifts not only as a mean to get necessary basic supplies, but also as a way to stay on good terms with converts and the Owambo kings, who had the power to expel Finns from their territory. It is likely that Liljeblad also received many of his objects gifts in connection to his missionary work.

Liljeblad in his study in Oniipa Missionary Station. Note the palm leaf containers under the table: this type of object might have been used as a household item at the mission stations and included in the ethnographic collection only at the point when Liljeblad returned to Finland. The Karl Emil Liljeblad Collection, University of Oulu.

Both elite and non-elite Aawambo were eager to exchange goods with missionaries. They directly affected the collection by deciding what objects were appropriate to convey as either gifts or payments. Liljeblad wrote that the Aawambo offered him items, such as knives, ostrich feathers and wooden cups. This type of transaction served at least two purposes. First, it served as a means of acquiring valued European goods. Second, the objects could be used as strategic gifts in order to strengthen social ties with Finns, who provided useful services, such as treatment for illnesses or paid work in the missionary stations. The Liljeblad Collection contains a high number of common household items, such as arrows, wooden cups and palm leaf containers. The Aawambo were most likely happy to trade such objects, as they were easily replaceable and did not hold any specific religious and social value. Some of the unused dishes, wooden tobacco containers and wooden sculptures were specifically designed and manufactured to be traded with missionaries. The collection also contains luxury items, such as omba (seashell) and ivory jewelry. Some unique gifts, like knives in copper sheaths, were also considered as fitting gift of honor from the local royalty. This likely explains why Liljeblad received this item as a token of appreciation from the king and Aawambo elite. Missionaries were sometimes a nuisance for the king, but they were also useful as advisers and traders. Thus, a good relationship and successful negotiations – marked by an exchange of gifts – were mutually beneficial.

The Liljeblad Collection contains more objects supposedly invested with spiritual power than any other Aawambo collection in Finland. It includes power-belts, amulets and instruments used by healers and diviners. Most of these items were collected during Liljeblad’s ethnographic field work. However, Liljeblad was able to obtain some of them during his missionary period. After his resignation from the FMS in 1919, he displayed these objects as examples of the “witchcraft” of Aawambo people in an exhibition called “the Africa Room” in his Finnish parsonages in Kirvu (1920–1922), Simpele (1922–1924) and Ruskeala (1924–1937).

The Aawambo considered sharing religious customs with outsiders to be a taboo. It is likely that Liljeblad received objects with spiritual power mainly from Aawambo converts, who were obligated to give up all items that missionaries understood to be relics of “heathenism”. The renouncement of “heathen clothes” was in some instances overseen by Liljeblad. These objects were then either destroyed or added to the missionary collection. The Aawambo converts, who gave up the objects in order to become part of a Christian congregation, were not necessarily aware that missionaries would preserve the very same items that they were systematically eradicating from Owambo.

Collectors and Mediators

So far, I have spent two weeks in Engela. I was able to set my eagles free. Now they are flying from carcass to carcass. I myself sit here, surrounded by great friendliness, and dig now and then something deeper about life …

Karl Emil Liljeblad to missionary director Matti Tarkkanen, Engela, 27 December 1930

In the 1930s, Liljeblad’s main aim was to collect oral folklore about poetry, songs and spiritual customs from eight Owambo polities: Oukwanyama, Ondonga, Uukwambi, Ongandjerna, Ombalantu, Uukwaluudhi, Uukolonkadhi and Eunda. This work later took form in Liljeblad’s ethnographic manuscript “Afrikan amboheimojen kansantietoutta” [Folklore of the Aawambo People of Africa]. His ethnographic work was motivated by the salvage paradigm. Liljeblad believed that Aawambo customs would disappear in a few years due to “Christianization” and the “European way of life”. He actively sought and purchased Aawambo objects in order to provide physical evidence of the dying customs that had been described in oral folklore. Most of the Aawambo were still non-Christian, but it seems that religious, social and economic change in Owambo made some Aawambo more ready to sell also objects invested with spiritual power. Liljeblad wrote in 1931 that he was now able to buy spiritual objects and rare “regalia” that were “previously thought to be almost impossible to get”.

Liljeblad in “the Africa room” in Ruskeala, Finland. The Karl Emil Liljeblad Collection, University of Oulu.

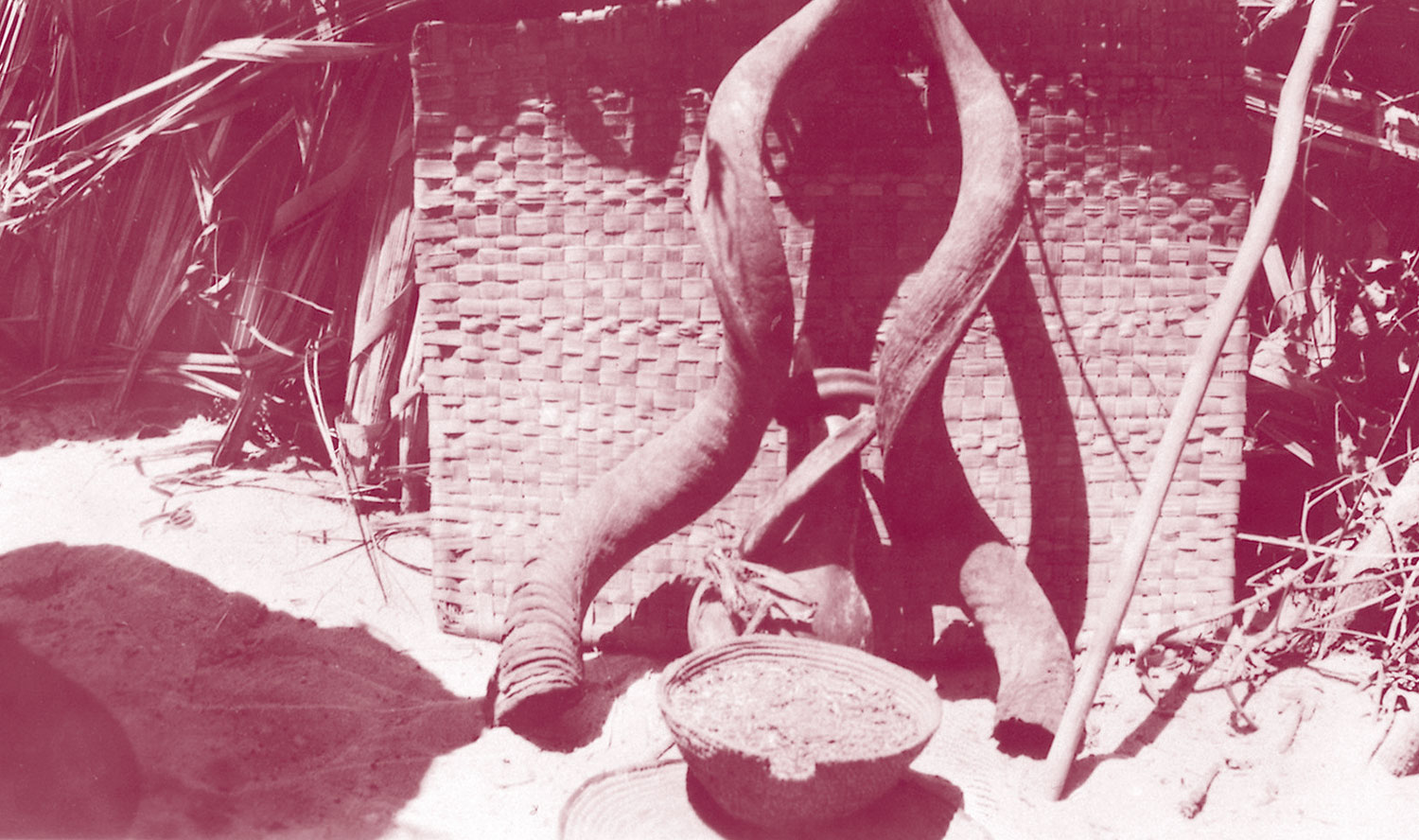

Liljeblad also used photography for recording Aawambo customs and objects. This photo depicts artefacts used at a girl’s initation ceremony, Ohango, in the early 1930s. The Karl Emil Liljeblad Collection, University of Oulu.

It is important to notice that Liljeblad did not collect ethnographic material alone. In the quotation above, “his eagles” refer to the Aawambo teachers, who collected mainly oral folklore, but also ethnographic objects for Liljeblad in 1930–1932. Liljeblad send each of his 25 assistants to different Aawambo communities to write down Aawambo customs. He paid both his assistants and informants, which likely encouraged them to participate in the research. He also gave his assistants a motivational speech, where he explained – at least to some extent – why folklore was collected. Liljeblad wrote that many of the assistants were enthusiastic about gathering ethnographic material. Since they were Christians working closely with the Finnish Owambo mission, it is possible that they shared a similar motivation for collecting with Liljeblad: preserving Aawambo heritage for future generations before it died out due to changes in religious beliefs.

It is evident that without the Aawambo assistants, Liljeblad would not have been able to gather such a vast corpus of Aawambo folklore. Due to scant historical evidence, however, it is more difficult to say for certain, what the assistants’ precise role regarding the acquisition of objects. As a former missionary, Liljeblad knew the language and customs. He had his own established ties with Aawambo communities. Therefore, he could gain access to objects that were not available for travelers just passing through. Still, Liljeblad was, for example, able to purchase an onkiinda (a healer’s basket with equipment) from a diviner woman only because one of his informants, Jairus Uugwanga, introduced him to the diviner. It is plausible to assume that the Aawambo assistants worked in this way as cultural brokers, who, while gathering oral folklore, had a formative role in connecting Liljeblad to suitable leads on objects. They might have even enabled Liljeblad to purchase the artefacts that were previously excluded from exchanges between missionaries and Aawambo.

Conclusion

The Karl Emil Liljeblad Collection embodies cross-cultural interaction and negotiated exchange between the missionary collector Liljeblad and members of the Aawambo community. It was formed as a joint effort. Although Liljeblad had ideas about what a collection should contain, this could not be realized without the Aawambos’ active participation. They designed and manufactured the objects and decided what to exchange with Liljeblad and what to withdraw from transaction. Both elite and non-elite Aawambos were eager to trade and exchange gifts with Liljeblad, and the collection contains a high number of common household items, weapons and jewelry as a proof of bartering and cementing friendly relationships. The Aawambo also had a crucial role to play as producers of ethnographic knowledge during Liljeblad’s ethnographic research between 1930–1932. They worked as informants, collectors and mediators, and participated directly in gathering oral folklore, and also traced objects for Liljeblad. Without their contribution, Liljeblad would not have been able to gather such a broad collection.

Bibliography

Cannizzo, J., Gathering souls and objects: Missionary collections. Colonialism and the Object. Empire, Material Culture and the Museum. Eds. Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn. London: Routledge, 1998, 153–166.

Gardner, H., Gathering for God: George Brown and the Christian Economy in the Collection of Artefacts. Hunting the Gatherers. Ethnographic Collectors, Agents and Agency in Melanesia, 1870s–1930s. Eds. Michael O’Hanlon and Robert L. Welsch. New York: Berghahn Books, 2000, 35–54.

Heintze, B., Hidden Transfers: Luso-Africans as European Explorers’ Experts in 19th Century West Central Africa. The Power of Doubt: Essays in Honor of David Henige. Ed. Paul Landau. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2011, 19–40.

Koivunen, L., Terweisiä Kiinasta ja Afrikasta. Suomen Lähetysseuran näyttely-toiminta 1870–1930-luvuilla. Helsinki: Suomen Lähetysseura, 2011.

McKittrick, M. Capricious Tyrants and Persecuted Subjects: Reading between the Lines of Missionary Records in Precolonial Northern Namibia. Sources and Methods in African History: Spoken, Written, Unearthed. Eds. Toyin Falola and Christian Jennings. New York: University of Rochester press, 2003, 219–236.

Miettinen, K., On the Way to Whiteness. Christianization, Conflict and Change in Colonial Owambo, 1910–1965. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2005.

Shigwedha, V., The Pre-Colonial Costumes of the Aawambo. Significant Changes under Colonialism and the Construction of Post-Colonial Identity. Aawambo Kingdoms, History and Cultural Change. Perspectives from Northern Namibia. Basel Namibia Studies Series 8/9. P. Sclettwein Publishing, 2006, 111–274.

Siiskonen, H., Trade and Socioeconomic Change in Owambo, 1850–1906. Helsinki: Suomen Historiallinen Seura, 1990.

Skyttä, J., Sadan vuoden tie. Emil Liljebladin Ambomaa-kokoelma lähetystyön ja etnografian reiteillä. Kaikille kansoille. Lähetystyö kulttuurien vuoro-puheluna. Toim. Seija Jalagin, Olli Löytty & Markku Salakka. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2010, 305–330.

Torrence, R. & A. Clarke, Excavating ethnographic collections: negotiations and cross-cultural exchange in Papua New Guinea. World Archaeology 48:2, 2016, 181–195.

About the Author

Kaisa Harju is a doctoral student in the History of Sciences and Ideas at the University of Oulu. She has studied the development of Finnish healthcare cooperation in Somalia and ethnographic missionary collecting in northern Namibia.