A Reflection: The Intersection of Trade Cloth and Indigenous Crafts Among the Vakavango

Maria A. N. Caley

Textiles can be intriguing and a medium to emphasize artisanal identity for fashion and textile designers. More importantly, textiles in Africa have a long history and cultural significance. Although some of the textiles found on the African continent originate from elsewhere, their adoption and existence are rooted in trade routes. The literature regarding trade cloth in Africa posits that manufacturers initially designed these textiles with their own aesthetics, which had nothing to do with the intended African market. The occurrence of trade cloths, now commonly referred to as African prints, represented a failed attempt to copy the traditional batik textiles of Indonesia. The printed copies of Indonesian batik textiles, produced by a Dutch manufacturer and rejected by Indonesians, found a new market in Africa. More textile manufacturers in Europe started to explore the new market in Africa by introducing more factory-printed textiles. This paper adopts and views the term trade cloth solely in terms of the purpose it served. These trade cloths were often transformed when accepted by indigenous groups in order to achieve a desired aesthetic or were renamed as a means of cementing the connection to the cloth. Ultimately, the trade cloths that were once foreign became embraced by Africans through a process of adoption and transformation.

Trade Cloth in Namibia

In the case of Namibia, unlike other parts of Africa, there is not a long history of the production of traditional textiles. Indeed, many of the textiles referred to as ‘traditional’ in Namibia only took root after being introduced by European traders. Ondhelela fabric, for example, was introduced to Aawambo by Portuguese traders from Angola, but has now formed a strong material culture identity in Namibia. This goes against the common assumption that ondhelela was introduced into Namibia by Finnish missionaries.

In Kavango, trade cloths underwent similar patterns of transformation as they were being introduced and adopted. Early trade activities by Vimbali black slave traders in Kavango, who came from the Province of Bie in South East Angola, brought cloth and European goods to trade among the Vakwangali, an ethnic group from Kavango. The trade cloths that were introduced among the Vakavango were embraced and given local names. Kavango trade cloths, for example, were known as lyosikwangali. These cloths were stripped in appearance and were similar to the ondhelela designs used by the Aawambo. Other local names for trade cloths included sikatu or sikato, which featured navy and white stripes and the maroon-coloured lyegeha that was unpatterned. Further research is needed vis-à-vis the meanings given to each type of cloth. In this short article, I will limit my analysis to the meaning behind the amakeya cloth.

Amakeya Cloth

European and African traders were the main agents for introducing trade cloth among ethnic Namibian groups, but they were not the sole agents. Missionaries also introduced fabrics that were used to sew Eurocentric clothing for children at the mission stations. The Catholic mission at Sambyu in Kavango presents a fascinating story of the amakeya cloth that was introduced among the Vasambyu community. The amakeya cloth had red, black and white zigzag patterns. The story of the amakeya cloth is widely spoken of among the Vakavango. However, efforts to trace the history of the introduction of this cloth have been insufficient and, what is more, the cloth no longer seems to be visible among the Vakavango.

As stated, amakeya cloth was introduced into the Sambyu community by the Sambyu Catholic Mission. M. Kaundu explains that amakeya cloth was brought in by Sister Ntine, a Catholic nun from Holland, who brought the cloth to Africa in order to be made into skirts for the girls attending the school at the Sambyu Mission. Various narratives tell of how this cloth came to bear the name amakeya, a foreign name. One particular story states that the name was taken from an Afrikaans poem by A. G. Visser, which featured a woman named Amakeia. This poem was well-known in Afrikaans literature. Amakeia is depicted as a heroic Xhosa woman who worked on a farm in South Africa during the colonial era. Amakeia fled to the mountains with a white baby when the farm was attacked during the Sixth Xhosa War of 1834–1836. The poem states that Amakeia and the baby were discovered at their hiding place by indigenous worriors portrayed as ‘spies’ and were both killed as she was not prepared to part with the baby. The relationship between Amakeia, the heroic Xhosa woman, and the cloth named amakeya of Vasambyu is baffling. Further research is need to ascertain why this name was chosen for this particular cloth.

It is intriguing how a cloth used in the Sambyu community came to possibly have an association with a Xhosa woman in a distant land. The relationship between the heroine Amakeia and the amakeya cloth seems to be a mystery, perhaps largely because of the way the cloth was presented to the Vasambyu community. Amakeya cloth seems to be the exception, when looking at the names given to trade cloths, in that it appears to have been named after a person. Other trade cloths were given names that either emphasized their aesthetic appeal or referenced a particular ethnicity, such as lyosikwangali in connection to the Vakwangali.

Many of the trade cloths disappeared from the market over the course of time, but a lot of them have recently been reintroduced by local Chinese textile trades. However, amakeya cloth has not been successfully revived by these new cloth traders. Kaundu explains that an attempt to revive amakeya cloth was made, but it had not taken root as the new design was not true to the original that had zigzag patterns that ran horizontally in red, black and white. The copy only features red and white stripes and the zigzag pattern runs vertically.

Indigenous Aesthetics and Trade Cloth

Cloth in Africa, including Namibia, has played a significant role in cultural practices and culture formation. Jennings states that cloth in African cultures was often used as currency, gifts, dowries, as well as symbols of power, artisanal identity, method of communication and spiritual protection. The trade cloths may have been foreign to the people, but they were embraced and even named with vernacular names to create a connection to the textiles. Shigwedha argues that not all trade cloth were adopted. Traditional values dominated the design and color choices of the Aawambo community and therefore only the cloths they preferred were adopted. Furthermore, trade cloth among the Aawambo and Vakwangali communities were boiled and smeared in olukala or rukura, an ointment made of crushed wood pulp of usivi (Ptercarpus Angolensis) in order to achieve the desired quality and appearance. Shigwedha also argues that not all trade cloths were accepted by Namibian communities. In short, indigenous people were still influenced by indigenous aesthetics when selecting textiles from traders. The same can be argued about amakeya cloth, because the Vasambyu community preferred this particular cloth as it resonated with their indigenous aesthetics. The zigzag patterns of amakeya are similar to the patterns on indigenous crafts, such as baskets, woodwork and pottery.

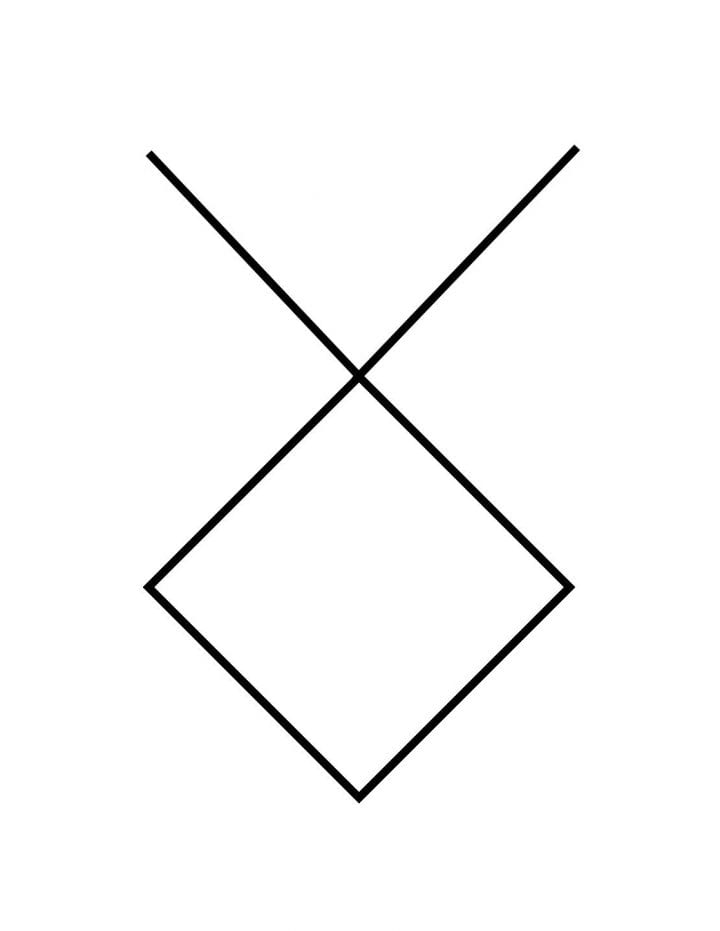

Kavango basket-weaving motif

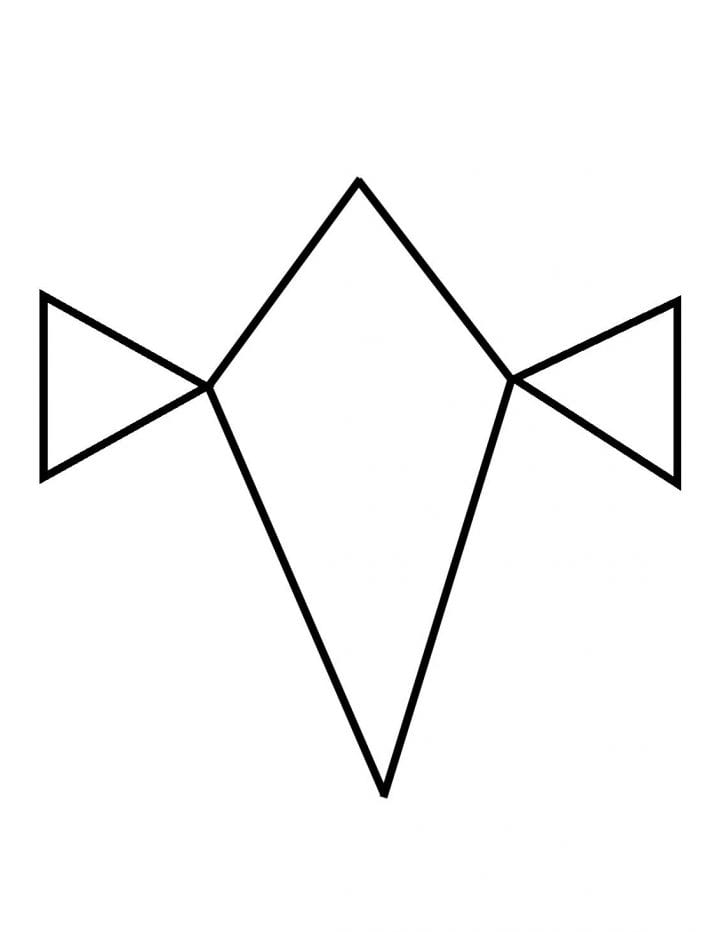

Holy Spirit motif

In the past, African crafts were perceived to be naïve and without much sound design aesthetic. The transformation of trade cloth among the Aawambo and Kavango communities undermines such a perception which reveals purposefulness and functionality. Moreover, indigenous craft making in Kavango demonstrates an aesthetic of clean lines and geometric shapes, which can be universal. The composition of decorations on indigenous crafts are well placed and are often applied for emphasis. In her research regarding handmade products in Namibia, Pokela illustrates how basketry artisans often chose imagery of leaves, trees, stars and flowers when decorating their baskets. It can be argued that even in indigenous craftmaking, decorations are designed and planned in advance. Kaundu, who is also a craftswoman, explains that motifs often used in basketmaking have meaning.

She explains that the motif shown in the first figure (Kavango basket-weaving motif) represents the relationship of women in a polygamous marriage: sometimes they get along and sometimes they do not. The women are represented as getting along cordially where the lines meet. In contrast, they are depicted as being antagonistic where the lines drift apart. Kaundu furthermore explains that the motifs on the basket are generally called mapi. However, the weaver may choose to compose her own motifs in order to express something personal. The other figure shows another motif, designed by Kaundu, which represents the Holy Spirit.

Although indigenous craftmaking in Namibia is rooted in traditional methods of production, the postcolonial craftsmen and craftswomen have succumbed to the demands of tourists to depict ‘exotic and romantic’ ideas about the region. The ‘exotic and romantic’ ideas of tourists are often associated with naivety and not necessarily an indigenous style.

Bibliography

Akinwumi, T. M., The “African Print” Hoax: Machine Produced Textiles Jeopardize African Print Authenticity. Journal of Pan African Studies 2:5, 2008, 179–192.

Hemmings, J., Hybrid Sources: Depictions of Garments in Post-colonial Textile Art. The spaces between textiles_art_design_fashion 2, 2004, 1–6.

Jantunen, T., Ose Vakavango Kukara kwetu. Unpublished manuscript 1963.

Jennings, H., New African Fashion. New York: Prestel Publishing, 2011.

McRoberts, A. C., Odelela: From Trade Cloth to Symbol of Contemporary Cultural Identity. Paper presented at the arts and indigenous knowledge systems in a modernising Africa. Pretoria, South Africa, 2013.

Labuschagne, H., How do we choose our heroes. (n. d.), https://www.labuschagne.info/amakeia.htm.

Likuwa, K. M., Voices from the Kavango: A Study of the Contract Labour System in Namibia 1925–1972. Doctoral thesis, University of Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa, 2012.

Pokela, L., Handmade in Namibia Design Collaborations in Artisan Communities. MA thesis, University of Art and Design, Helsinki, Finland, 2008.

Sarantou, M., Namibian Narratives: Postcolonial Identities in Craft and Design. Doctoral thesis, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, 2014.

Shigwedha, V., Pre-Colonial Costumes of the Aawambo, significant Changes under Colonialism and Construction of Post-Colonial Identity. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia (2004).

About the Author

Maria A. N. Caley is an Assistant Lecturer (MA student) at the University of Namibia. She is a specialist in fashion and textile design. Her work explores traditional Namibian clothing and transformations into fashion and contemporary textiles.