Lessons to Learn from the Story of Rosa

Anna Rastas

On 8 June 1888, a Finnish newspaper, Wiipurin Uutiset, published an announcement about a girl of mixed African and European descent “who was born and baptised in Africa” and arrived in Finland with missionary K. A. Weikkolin and his family. The girl’s name was Rosa Clay (later Lemberg). As far as we know, she was born in 1875 in Omaruru in present-day Namibia. Based on what Rosa herself recited to Arvo Lindewal, who wrote Rosa’s first biography (Rosalia 1942), she was a child of a local woman, Feroza Sabina Hasara, and a Briton named Charles William Clay. She was still a small child when she was taken from her mother and, with her father’s permission, placed in a missionary school in Owambo run by the Finnish couple Karl and Ida Weikkolin. Later, they decided to bring Rosa to Finland. They promised her father that in Finland she would have the opportunity to continue her studies so that she could return to Africa as a missionary.

Rosa went to school in Finland and lived with the Weikkolin family, but she was expected to do housework and was forced to perform at church gatherings in various cities. She had to make money for the church by selling pictures of herself. In her memoirs, Rosa makes it clear that Ida Weikkolin was not as warm-hearted and altruistic a Christian benefactor as Ida presents herself in her own 1895 memoirs. For example, Rosa tells how Ida slapped her when she tried to refuse to sing songs for strangers in an African language that she did not even know. Rosa’s relationship with Karl Weikkolin seems to have been better.

Rosa received a good education in Finland. She became a teacher and worked in various schools, including in Tampere. Although her everyday life was shadowed by cruel racism, she also had many friends, and her talents as a singer and choir leader were praised in Finnish newspapers. In 1904, instead of returning to Owambo, which had been the original plan for her, Rosa, like many Finns in those days, moved to the United States. There, she married Finnish immigrant Lauri Lemberg and had two children. Rosa was active in Finnish immigrant communities, including as a choir leader and a Finnish-language teacher in summer schools for the children of Finnish immigrants. She never returned to Europe, nor to Africa. She died in 1959 at a Finnish rest home in Covington, Michigan.

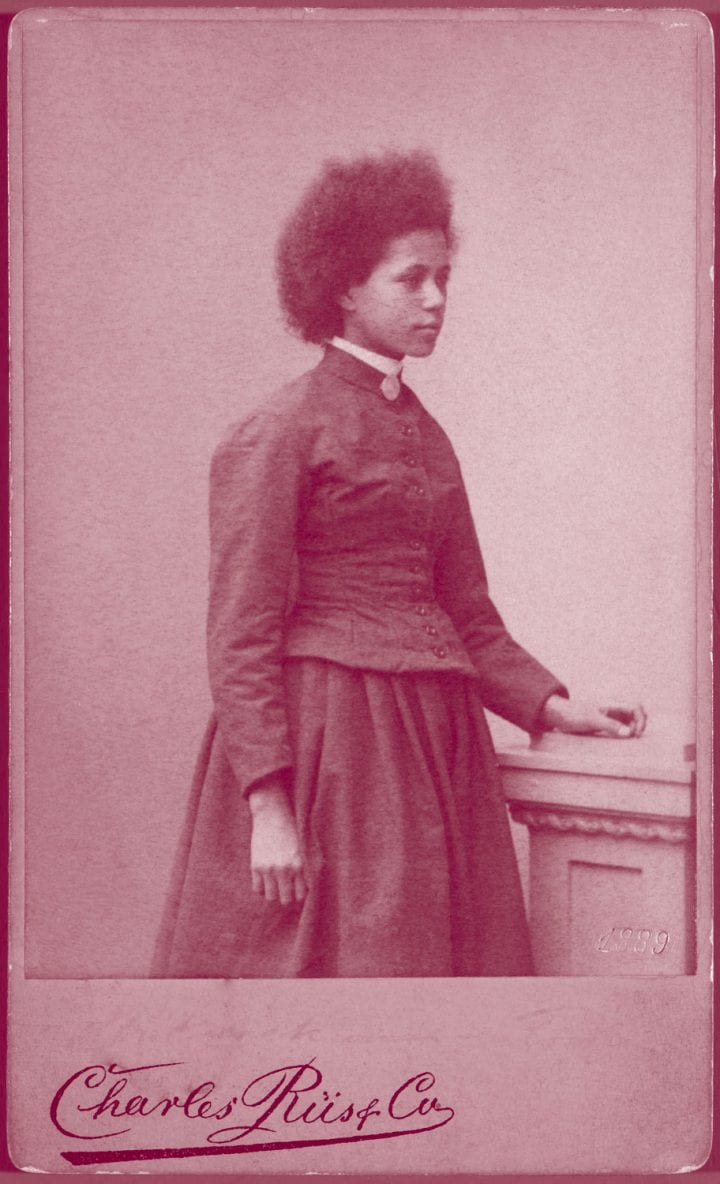

Rosa Clay was photographed by Charles Riis & Co. soon after arriving in Finland (1889). The Finnish Heritage Agency.

Almost everything we know about Rosa’s childhood in Africa and Finland is based on the first chapter of her memoir, Rosalia, which was published in 1942. It was published in Finnish in the United States and written by Rosa’s friend and fellow Finnish immigrant Arvo Lindewall. For various reasons, not everything in the book can be treated as historical fact. However, documents available in Finnish archives confirm many points.

Rosa´s story never drew much attention in Finland, although there were a few articles about her in newspapers and magazines in the 1950s and 1960s. Rosa arrived in the United States with a Finnish passport, but the Ellis Island archives hold an arrival document on which the word ‘Finnish’ was crossed out by immigration authorities and replaced with “African (Bl. [black])”. Still, as a person of mixed parentage in the Northern European immigrant community, her life was probably easier than many others of African descent. She was sometimes called “the only black Finn”, referring to her African roots, but also indicating her acceptance as a Finn in the Finnish immigrant communities. Because of racism in the United States, Rosa’s children decided to hide their African heritage.

Rosa’s life in the United States is better documented than her childhood because of her many activities in Finnish immigrant communities in multiple states. In 1993, the first U.S. study of her life was written by Eva Erikson, an emeritus professor of history who had been one of Rosa’s students in a Finnish-language summer school. Yet, Erickson’s study and Rosa’s story in general remained overlooked in Finland until 2010.

In the early 2000s, during my research projects on the history of Africans in Finland, I collaborated with a Finnish journalist, Leena Peltokangas, to find out more about Rosa’s life, both for my studies and for Peltokangas’ radio documentaries. In 2010, Peltokangas’ documentaries about Rosa and other early “Finns of African background” were broadcast by the Finnish Broadcasting Company. Rosa’s story was also told in 2010 in Mia Jonkka’s TV documentary Afro-Suomen historia (The History of Afro-Finns) and in an article based on Erickson’s book, in Finland’s largest newspaper Helsingin Sanomat. An English-language version of this article was published online. Thanks to all these journalistic documents many people in Finland got to know the story of the “the first Finnish African”, as Rosa is often called, although her status as being “the first one” cannot be confirmed as a historical fact.

Since 2010, Rosa’s name and story have been referred to in many of the social and cultural spaces that I enter during my research projects on the African diaspora in Finland. Her story seems to be particularly inspirational to artists and activists of African descent. The visual artist Sasha Huber has made a portrait of Rosa, whilst the dancer/choreographer Ima Iduozee named his performance celebrating Finland’s 100th year of independence after Rosa. She has also been mentioned in many of the interventions by activists against racism. In early 2019, I was approached by an anti-racism activist who wanted to talk about an initiative to name a street after Rosa. As far as I know, none of these artists or activists have roots in Namibia. Yet, they identify with Rosa’s story and see it as a part of their history in Finland, with ‘their’ meaning people of the African diaspora, whose lives are marked by colonial relations in a different manner than those of other Finns; people who see the world differently because of their position in racialized social relationships; and/or people whose Finnishness is questioned because of their background despite their contributions to Finnish society.

What has attracted my attention is that the artistic and activist projects related to Rosa do not necessarily seek to offer further information about Rosa’s life. Instead, for many people, Rosa – or the figure of Rosa – seems to be a token. The rapidly-growing group of Finns of African descent can finally show that “we also have a history here” and that this history means that the white majority must stop calling Finns of African descent and other racialized minorities “immigrants”. Rosa’s story is needed in order to identity and place the political struggles of many racialized minorities in Finland. She has been given a role as a pioneer: the first African who was granted Finnish citizenship (or, more accurately a citizen of the Grand Duchy of Finland), the first black teacher, the first black choir leader, etc. Even today, many artists and other professionals who belong to racialized minorities in Finland seek “other people like them” to create collectives in which they can share their experiences of othering, because, unlike in Rosa’s time, Finns today who have racialized minority backgrounds can join together and imagine their “future minority histories”. For these Finns, Rosa’s story as a person born in what is now Namibia is not as important as that she was an African and a Finn with African roots.

Nonetheless, the fact that she was brought to Finland from Owambo does matter. Her story reminds Finns of their colonial complicity, something about which people of the African diaspora, in particular, have tried to raise in discussion. Finns of an African background see things differently than Finns from a white-majority background, who grow up surrounded by the discourse of Finnish exceptionalism. In this case, this means the common idea that “Finns, who never had colonies, cannot be racists”. Closer, critical reading of texts, memoirs and other documents written by Finns during colonial times reveals that Finns, like other Europeans, had worldviews determined by colonial thinking and knowledge. Rosa’s herstory invites us to learn more about the histories of both Namibia and Finland and the mutual history of the two countries, although the events and relationships that connect the two mean different things for the peoples of each land. For example, reading the memoirs of Rosa and Ida simultaneously clarified for me the need for more critical reading about the encounters between Finnish missionaries and the people who lived in what is now Namibia. Even if these encounters were not as violent and harmful to these people as for those in many other African places, they were not based on equal rights. In addition, our knowledge of these encounters still shapes the way Finns see not only Africa and Africans but also themselves. We know little about how Namibians interpret these encounters.

Seeing how important the figure of Rosa has become for so many Finns of African descent inspired Peltokangas and myself to return to her story again, this time, to ask what we could learn from it. Our analyses, published in Finnish in 2018, studied both power relationships and the various aspects of Rosa’s personal herstory, including age, gender, race, nationality and class, all of which mattered. Her memoir as an immigrant in Finland and the United States also encouraged us to compare her experiences to those of migrants today.

Race mattered in various ways, and being an African of mixed Afro-European parentage had multiple meanings in Rosa’s life. She was not the only child at the missionary station in which she grew up, yet the Weikkolins chose her as the child who should get an education abroad. Her father’s background as a white European was probably at least partially responsible for this. As a child who was born into particular circumstances, Rosa had very little, if any, power over adults.

In Finland, few people were able to encounter Rosa as a person, instead of a representative of a different race. But, as a young woman there, Rosa was an educated person whose class position was better than, for example, that of my own great grandmothers of the same time, who never had the opportunity to go to school. After moving to the United States, Rosa, like many migrants today, had to settle for lower-paid jobs available to immigrants. Nevertheless, her education and previous class position became useful social capital among the less-educated Finnish immigrants, which – in addition to the fact that in the United States, Finns were considered ‘less white’ than some other European immigrants – probably made it easier for her to integrate into a form of migrant Finnishness.

For me, Rosa’s story has not ended. She keeps whispering new questions in my ear. As an adoptive mother of two (now grown-up) children born in Ethiopia, I can hear her asking “Why is no one interested in what my childhood in Africa was really like? Or how my mother felt when I was taken from her? Or how I felt when I had to leave my birth country and continue my life with a new family in a strange world among people whose language I couldn’t even understand?” I also think about her as a teacher, a peer, who reminds me of the Eurocentric epistemology underlying academic knowledge: “How is your worldview, and the knowledge on which your studies and teaching are based, determined by the colonial relationships that defined my life as well as the relationships between Finns and the people in my birth country?” I feel strongly that the next exploration of Rosa’s story should be done together with, or, by researchers in her birth country. I feel that we owe that to the child who was taken from her mother long ago.

Bibliography

Erickson, E., The Rosa Lemberg Story. Superior Wisconsin: The Työmies Society, 1993.

Jonkka, M., Afro-Suomen historia. TV documentary, part 1. YLE Teema, January 2010.

Jonkka, M., Rosa, Finland’s first black citizen. Helsingin Sanomat 24.1.2010.

Lindewall, A., Rosalia. New York: Kansallinen kustannuskomitea, 1942.

Peltokangas, L., Rosa Suomesta – ensimmäisiä afrikkalaisia etsimässä. Radio documentary. Yle Radio 1, 14.1.2010.

Peltokangas, L., Afrikka Suomessa: Rosa Clayn tarina. Radio documentary. Yle Radio Suomi, Tampereen radio, 31.1.2010.

Rastas, A., and L. Peltokangas, Rosan jäljillä kolmella mantereella. Tulkintoja ylirajaisuudesta ja muuttuvasta suomalaisuudesta. Satunnaisesti Suomessa. Toim. Marko Lamberg et al. Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 97. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2018, 86–103.

Rastas, A., The emergence of race as a social category in Northern Europe. Relating Worlds of Racism: dehumanisation, belonging and the normativity of European Whiteness. Eds. Philomena Essed et al. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Rastas, A., Talking Back: Voices from the African diaspora in Finland. Afro-Nordic Landscapes: Equality and Race in Northern Europe. Ed. Michael McEachrane. New York: Routledge, 2014, 187–207.

Rastas, A., Reading history through Finnish exceptionalism. ‘Whiteness’ and Postcolonialism in the Nordic Region. Eds. Kristin Loftsdottir & Lars Jensen. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2012, 89–103.

Weikkolin, I., Lähetyssaarnaaja Weikkolin’in viimeinen matka Afrikkaan vuonna 1890–1891. Helsinki, 1895.

About the Author

Dr. Anna Rastas is Docent of Social Anthropology at Tampere University and Docent of European Ethnology at The University of Helsinki. She works as an Academy of Finland Research Fellow at Tampere University. Her fields of expertize include ethnic relations, research on racism and anti-racism, transnationalism and African diaspora studies, critical heritage studies and childhood and youth studies.