Relief and Salvation: The Famine Relief Activities of Finnish Missionaries in the Ondonga Region, 1908–1909

Essi Huuhka

When the first Finnish missionaries arrived in the Ondonga kingdom in 1870, their goal was to spread the Christian message and to create local parishes. Their work took many forms during the subsequent years. Popular imagery used to portray missionaries preaching to local people under the canopy of trees, but in reality the missionaries also had to take care of their households, socialize with the local people and the local king, provide medical aid, trade, learn the local language and then translate religious texts, and write dozens of letters to Europe – among other things. The Finnish missionaries also distributed relief, which peaked in the years of famine in 1908 and 1909 that occurred when the crops failed.

In this text, I concentrate on the famine in Ondonga at this time as an example of relief carried out by Finnish missionaries. At the beginning of the twentieth century, poor relief was a continuous part of the work performed by the Finnish missionaries in German South West Africa. Poor relief included distributing famine food, objects and other goods, such as pearls, tobacco or clothes, for the needy local people. At that time, German South West Africa had just endured the Herero and Nama genocides and the German interest in Owambo was increasing. In May 1908, the military officer Victor Franke visited Ondonga and the Finnish missionary Martti Rautanen worked as his interpreter and guide during this visit. Some months later a serious famine hit the region.

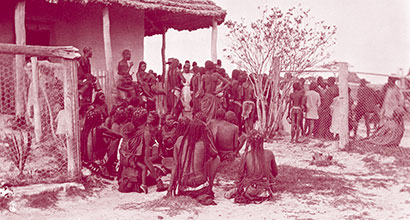

The Finnish missionaries first came into contact with the Aawambo in the 1870s. The mission stations became places visited by the local population for a variety of reasons. They were places for socializing, getting medical aid (especially after the first medical doctor, Selma Rainio, who was later known as Kuku, arrived in 1908), learning to read and write, learning about Christianity, becoming acquainted with western lifestyles and also to trade with the missionaries. In this regard, unsurprisingly, many local people who suffered hunger when the crops failed, also looked for support at mission stations. This happened in 1908 and 1909.

Local people gathered at the mission station in 1911. The Finnish Heritage Agency. Photograph: Hannu Haahti.

The food that was distributed was usually millet plant (omahangu). The Finnish missionaries used to buy food from nearby regions where food was less scarce, but in 1908–1909 they also received supplies from the German administration. This was linked to Franke’s visit to Ondonga some months earlier. Rautanen wrote to Franke and asked if it was possible to receive some famine food in the north of the region. This was the first time German famine food was sent. They mainly sent flour, rice and preserved vegetables, but the local people and the missionaries criticized the quality of the food. The missionaries wrote in their letters that many Aawambo would have rather eaten omahangus than rice. Another practical problem was that the missionaries had to transport the food from Outjo to Owambo, meaning a long journey with the missionaries’ ox wagons.

The missionaries described their concrete actions in the letters they sent to Finland to be published in the missionary society’s periodical, entitled Suomen Lähetyssanomia. In their letters, the missionaries described their organized efforts to distribute relief. The missionary Anna Glad, for example, wrote about how she wrote down the names of the receivers. She probably abandoned this practice later as she noticed it was impractical. Another way to distribute food in an orderly manner was to organize the people in lines and to call them one by one. In their letters, missionaries also wrote that the portions were quite small, but they were convinced that it was better than nothing. These letters need to be read in context: they were meant to be read by so-called “missionary friends”, meaning those Finns who were interested in the missionary work and who were potential donors. Consequently, the missionaries needed to create an image that underlined the reasonable character of their efforts.

In order to make ends meet and also to prove to the donors and the board of directors of the Finnish Missionary Society that their actions were rational, the missionaries wrote about how they categorized the Aawambo according to need. This was necessary in order to convince the readers and supporters that aid was only distributed to those who really were poor and were suffering from a scarcity of food. Thus, the missionaries distinguished between the deserving and those in less urgent need of food. In general, the question of being able to accurately identify a real need for sustenance had been at the center of discussions relating to poor relief for centuries, and the same discussion is relevant in the twenty-first century. For example, Martin Luther wrote about deserving and less deserving poor and the principles of poor relief in the sixteenth century, and it was still a relevant question at the beginning of the twentieth century. However, in the case of the famine relief in Ondonga, it is interesting to note that the categorization was not connected to the recipients’ religious convictions. This meant that food relief was given to local Christians as well as non-Christians. This is noteworthy because usually a distinction according to the religious belief was the most relevant factor for the missionaries.

The relief by the Finnish missionaries can be understood as a necessity, as they had to get along with the local people. In this regard, they also undertook general trade with the indigenous population. Thus, providing food exchanges and also distributing emergency aid during the food crises was a natural form of their everyday work. However, their relief work also had a religious background. It was based on the teachings of the Bible and old philanthropic traditions. In Europe, Christian philanthropy has long roots and Christian charity was also a common phenomenon in Finland. The Grand Duchy of Finland was a rural land in the late nineteenth century. During the severe famine of 1866–1868 around eight per cent of the population died of hunger in Finland. Eastern and northern parts of Finland were still relatively poor at the beginning of the twentieth century. Thus, the missionaries had personal experience of poverty and food shortages even before they arrived at their mission station in southern Africa.

The religious background and strong Christian faith of the Finnish missionaries could be a reason why they decided to help both local Christians and non-Christians. The idea of brotherly love and the stories and teachings of Jesus in the New Testament underline the model that no distinctions should be made between worthy recipients. Furthermore, the missionaries viewed the famine as an act of God. The Finnish missionaries understood the biological and geographical reasons behind the famines, but ultimately they believed that it was God’s will. Famine and relief depressed many missionaries and many wrote in their letters about how exhausted they were, but they trusted that God had a reason for his actions. Leaning on God and their faith gave the missionaries strength and a motive to push forward.

Christian values guided the practical and religious work by the missionaries at every level. Preaching in general was an important part of the daily missionary work. Religion was also present in the situations in which food was given to the poor. It can be argued that the Finnish missionaries fed both the bodies and souls of the receivers, because the distributed food was combined with the religious message of Salvation. After the missionary hospital was built in the early 1910s, evangelists also worked there. Thus, evangelism was also part of the famine relief. In their letters the missionaries described how they delivered speeches, sang hymns and organized full religious services when people gathered at the missionary station. The missionaries could also speak to the needy on an individual basis. Only after this religious prelude was the food distributed. Even though the recipients of relief were effectively compelled to listen, the missionaries understood this as a functional method and they thought that it could eventually lead to conversions.

To conclude, the Finnish missionaries had many differing motives for undertaking their famine relief. The most significant factor was probably their Christian faith and religious worldview. Poor relief traditions and local circumstances also created the preconditions in which the missionaries worked. Even though the Finnish missionaries offered help, their actions and food stocks were limited. Nevertheless, given relief played an important and vital role, especially for those Aawambo who had no other source of nutrition at the height of the famine. The Finnish missionaries offered both secular relief and religious salvation. It remains unknown how many Aawambo were converted as a direct result of receiving food relief during the famine. Nonetheless, crises like the famine of 1908–1909 created situations that made the Finns and Aawambo come together.

Bibliography

Brewis, G., ‘Fill Full the Mouth of Famine’: Voluntary Action in Famine Relief in India 1896–1901. Modern Asia Studies 44:4, 2010, 887–918.

Eirola, M., The Ovambogefahr. The Ovamboland Reservation in the Making. Political. Responses of the Kingdom of Ondonga to the German Colonial Power 1884–1910. Rovaniemi: Pohjois-Suomen historiallinen yhdistys, 1992.

Huuhka, E., Feeding body and soul: Finnish missionaries and famine relief in German South West Africa at the beginning of the 20th century. Nordic Journal of African Studies 27:1, 2018.

Häkkinen, A. & H. Forsberg, Finland’s famine years of the 1860s: A nineteenth-century perspective. Famines in European Economic History: The Last Great European Famines Reconsidered. Eds. Declan Curran, Lubomyr Luciuk & Andrew G. Newby. London: Routledge, 2015, 99–123.

Jalagin S., I. M. Okkenhaug & M. Småberg, Introduction. Nordic missions, gender and humanitarian practices: from evangelizing to development. Scandinavian Journal of History 40:3, 2015, 285–297.

McKittrick, M., To Dwell Secure. Generation, Christianity, and Colonialism in Ovamboland. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2002.

Ó Gráda, C., Famine: A Short History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Oermann, N. O., Mission, Church and State Relations in South West Africa under German Rule (1884–1915). Stuttgart: Steiner, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1999.

Peltola, M., Martti Rautanen. Mies ja kaksi isänmaata. Helsinki: Suomen Lähetysseura, Kirjapaja, 1994.

About the Author

Essi Huuhka is a doctoral student at the Department of European and World History, the University of Turku. In her doctoral thesis, she studies the Finnish mission in South West Africa at the beginning of the twentieth century. She focuses on the humanitarian thought and actions of the Finnish missionaries.