Step by Step, Brick by Brick: The First Decades of the Onandjokwe Hospital

Heini Hakosalo

This chapter discusses the Onandjokwe Hospital – its facilities, equipment, personnel, patients, diseases and treatment methods – during the first decades of its existence. The development of the hospital was influenced by a variety of different actors and by different and sometimes conflicting religious, humanitarian and political interests.

First of all, there would not have been a hospital without Aawambo people supplying the patients, staff and the supporting community. The king of Ondonga had donated the land on which the hospital would stand, and his successors offered patronage and protection. Second, the hospital was owned by the Finnish Missionary Society (FMS), which paid the salaries of the Finnish staff and contributed towards the building and running costs. Third, the Finnish missionaries posted in Owambo relied on the services of the hospital, and the missionaries’ meetings had a say in its affairs. The individual who left the deepest mark on the early history of the hospital was Dr. Selma Rainio (1873–1939), who founded the hospital in 1911 and ran it until 1932. She was succeeded first by Dr. Anni Melander, who worked at Onandjokwe from 1932 until 1938, and then by Dr. Aino Soini, the physician from 1938 to 1947. Fourth, the colonial powers also had a stake in the hospital. During the German period, prior to 1915, the hospital was minuscule and the German presence in the area relatively weak. The administration of South-West Africa (SWA), established as a South African mandate in 1920, had a firmer grip on the region and showed more interest in the Finnish medical mission. The administration subsidised the hospital on a more or less regular basis, and the Finns – somewhat grudgingly – delivered the statistics and reports it requested in return.

Facilities and Equipment

In 1904, when Rainio was still a medical student in Helsinki, she received a letter from Hilma Järvinen, a missionary posted in Ondonga. Järvinen expressed her joy over Rainio’s decision to work in Africa one day and added sanguinely: “If you come, Selma, then of course there will also be a hospital.” Järvinen was both right and wrong: there would indeed be a hospital, but it would be the result of a long and painstaking process rather than a foregone conclusion. Rainio arrived at the Oniipa Station in December 1908. She had a room at the station, but no facilities for medical work. Patients started coming as soon as she arrived. Their numbers were increased by a famine prevailing in Owambo that year. She saw them on the porch or in the yard, and a few huts were hastily erected for those too weak to return home.

Rainio devised a plan for a hospital. It comprised two buildings, one primarily intended as a dwelling for the Finnish staff and the other for the patients. The plan was mailed to the FMS Board for review in July 1909. Six months later, the Board agreed to finance one of the houses. The chosen site was a slightly elevated, treeless spot, 700–900 meters from the Oniipa Station. A missionary man was appointed to oversee the building work. This phase, too, took longer than expected. Rainio was able to move in January 1911, and the hospital was inaugurated in July 1911.

The inauguration of Onandjokwe Hospital on 9 July 1911. FMS Archive, Finnish National Achive.

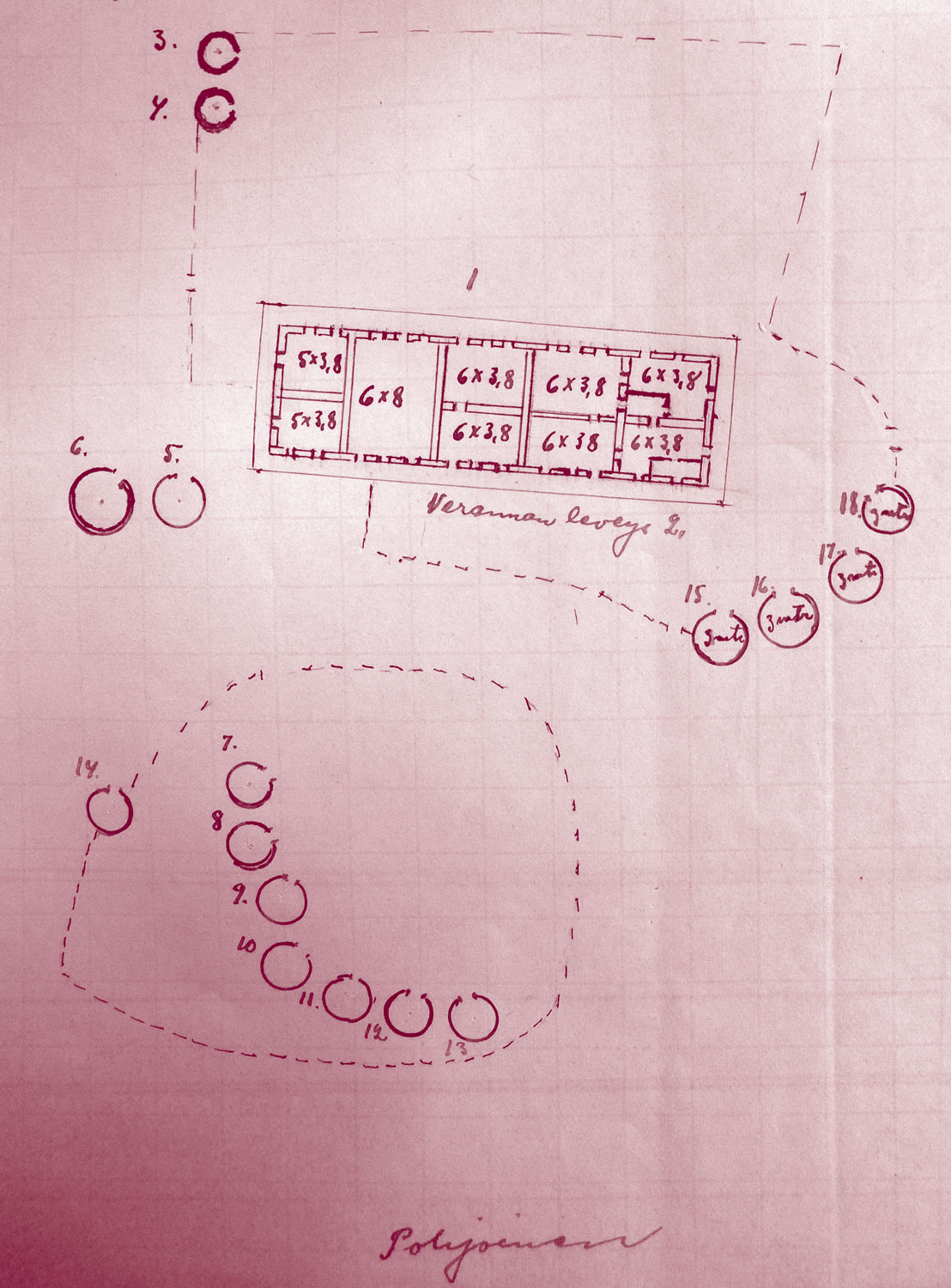

A drawing of the hospital in 1911. The drawing was made by Rainio and was included in the 1911 inspection report (FMS Archive, Finnish National Archive). The carriage shed lies outside the picture, and the round huts are – according to the ledger – somewhat misplaced with regard to the house.

The building was constructed of adobe brick and had an overhanging, tin-plated roof, supported by tree trunks. Its nine rooms included a kitchen and a dining room, the living quarters of the doctor and the nurses and a guest room. An examination and operating room were situated at one end of the house. Rainio was delighted to finally be under her own roof and was initially well pleased with the site: “Our house lies on an open ‘hill’ with a wide view to all directions. A cool breeze can be felt even at noon, with no trees or bushes to block it.” The downsides became apparent with time. Most importantly, it would prove difficult to find enough food and water for the cattle of two major mission stations so close to each other.

The next major undertaking was the construction of an outpatient clinic in 1912. Rainio, having learned her lesson, neither sought formal approval from the board in advance, nor asked a male missionary to lead the construction work. Rainio and her housekeeper, Selma Santalahti, oversaw the process themselves and also took part in the hands-on construction work. Rainio complemented Santalahti’s workmanship and referred to the building, with some pride, as “the clinic built by women”. The clinic had four rooms: an examination room, a pharmacy, an operating room and a maintainance room.

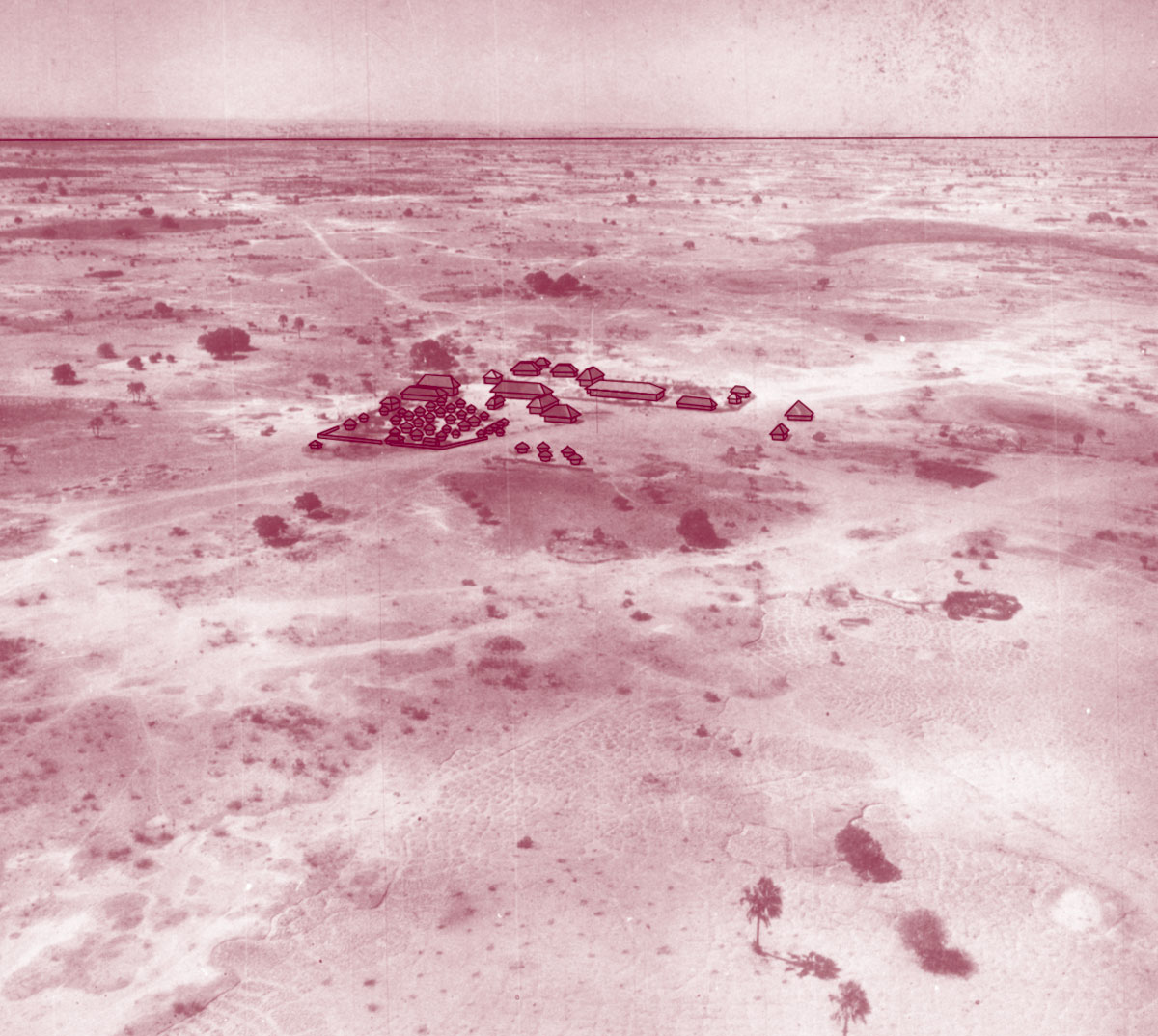

Rainio had placed her first native inpatients in small round huts because nothing else was available. The “hut system”, initially intended as a temporary solution, became a long-standing one. The small, round huts had a thatched roof and a door but no windows or furniture. The hospital provided the patient with a palm leaf mat or two, a blanket and some firewood. Patients cooked their own meals, either bringing the food with them or getting it from the hospital. In 1911, there were seven inpatient huts. In 1925, the number of huts was 23, including two huts for lepers at some distance from the others. Their number further increased in the 1930s. Onandjokwe inpatients were housed in huts until 1958, when a fire destroyed much of the hospital and led to its modernization.

The hut system had both economic, hygienic and social advantages. Huts could be built quickly and cheaply from local materials. The roof was easy to renew, and the interior walls could be repainted with clay when dirty. A badly deteriorated or defiled hut could be taken apart and replaced with a new one. In the aftermath of the devastating 1915–1916 famine, all the patient huts were taken down at once and gradually replaced with new ones. A further advantage was that a hut could accommodate the family member(s) who often accompanied a patient to the hospital. Their presence added to patient sociability and wellbeing, and significantly reduced the workload of the salaried staff. In fact, it is doubtful that the small and overburdened Finnish nursing staff would have been able to cope without the contribution of the patients’ family members.

Onandjokwe inpatient huts just before a storm. FMS Archive, Finnish National Archive.

An aerial photograph of Onandjokwe Hospital in 1940, with the outlines of the major buildings accentuated. FMS Archive, Finnish National Archive. Image enhancement: Ella Kantola.

A long-waited new operation room was finished in 1939. The old one had been inadequate for some time. It was small, dark and difficult to keep clean. The roof was made out of lath and sealed with clay, and a sheet had to be hung between the roof and the operating table to prevent debris from floating from the roof to the operating area. As the main source of light was a large, east-facing window, operations had to take place during the morning hours. During night-time emergency operations, a person was needed to hold an electric torch. The need for a new operation room became more pressing when Melander replaced Rainio and surgical activities increased. FMS refused to pay for the building, but the SWA administration came to the rescue: Mrs. Hahn, the wife of the Native Commissioner, gave birth to their firstborn at Onandjokwe and the grateful father donated building materials for a new operating room.

The hospital was equipped in much the same way it as was constructed, that is, slowly and gradually. Rainio arrived in late 1908 with a set of medical instruments and a microscope. Mission supporters sent linen and bandages. When Rainio was returning to Africa after her first furlough (1919–1922), she managed to persuade the FMS Board to pay for six hospital beds (excluding mattresses). That she considered this a major achievement is an indication of the scale of FMS investment at the time. In 1932, the hospital equipment included a centrifuge, two scales and a steam sterilizer. By her second furlough (1933–1936), Rainio was already a minor celebrity in Finland and received many donations, including medical instruments, an X-ray machine and a generator. Various labor-saving devices also found their way into the hospital in the course of the 1920s and 1930s: they included a typewriter, a sewing machine, a telephone, a wringer and, last but not least, a mechanical mill for grinding grain.

Human Resources

The physician was the self-evident centre of the hospital. The Onandjokwe physician was also a station manager, a personal physician to all Finnish missionaries and their families, and the head of the Finnish medical mission, which comprised not only the Onandjokwe hospital but also several dispensaries at various mission stations and a small hospital at Engela Station. When Melander arrived in Onandjokwe in 1932, she found a hospital that was in many ways different from the ones in which she had worked in Finland. However, it is clear that Onandjokwe was no longer a makeshift arrangement, but an institution with its own institutional culture and well-established practices. Melander thus wrote to a friend: “She [Rainio] has accomplished quite a feat here, having brought these buildings into existence and having organized the work. It’s like a machine that runs by itself, I just step in and take Kuku’s place. Of course there are things I would like to change, but these changes, too, need to be considered very carefully.”

A sole doctor can do little without nurses and other helpers. Rainio learned this the hard way during her first six months at Oniipa, when much of her time went into tasks that required no medical expertise whatsoever. The arrival of Selma Santalahti, a capable woman with some nursing training, in June 1909, was highly welcome but not sufficient to solve the workpower issue. The first trained nurses, Karin Hirn and Ida Ålander, came from Finland in July 1911. Shortage of trained nurses was a recurrent concern in Rainio’s correspondence. The number of Finnish nurses working at the hospital between 1909 and 1947 varied between two and four. Many of the nurses soon “wore out”, that is, they lost their physical stamina because of malaria or other diseases and overexertion.

The lack of trained nursing staff was, to an extent, compensated by Aawambo people being trained on the job. Rainio’s very first assistant was a young man called Silvanus, who worked at the hospital from 1909 until 1911, when he left to work in the mines. He was followed by many other male and some female auxiliary nurses and orderlies. The evangelist was a local man, as were the driver, the foreman and the cattle herders. The numerous “station children” also helped around the house and the hospital.

Regular training of native nurses started relatively late. Rainio was initially not keen on the idea, as she had come to believe that there were features in the local culture and society that made professional nursing and Aawambo people, and especially Aawambo women, a poor match. Rainio’s extreme workload probably played a role too; she was not eager to take on new tasks. But neither did she object when Karin Hirn launched the first nurses’ training course in 1930 and regular three-year courses in 1934. Rainio contributed to them by giving lessons on anatomy and physiology, and the health education handbook she had written in the Oshindonga language was used as a textbook. Towards the end of her life, Rainio gave credence to native nurses and regretted that she had not delegated them more responsibility earlier.

Patients and Treatment

When the nucleus of the hospital first came into being, Owambo was a population-rich area with practically no biomedical health care provision, but patients had no trouble finding the hospital. The number of patients varied considerably from year to year, but the general trend was upwards. In 1910, for instance, there were 4609 outpatient visits and 148 inpatient stays. In 1936, the hospital treated 5186 outpatients and 746 inpatients. The number of “beds” in the inpatient huts varied between 40 and 60 in the 1930s and 1940s.

The nucleus of the hospital staff: Selma Rainio standing and Selma Santalahti sitting. FMS Archive, National Archive.

Malaria was ubiquitous. Rainio was criticized in private for assuming that everyone suffered from malaria and that every disease was complicated by it. In 1911, the largest single disease category in the hospital records were various forms of severe anaemia, usually caused by intestinal parasites. Venereal diseases, tuberculosis, influenza, leprosy, tuberculosis, anthrax and plague also received a lot of attention in reports and correspondence. Drought and crop failure were accompanied by hunger-related conditions. These were particularly common in 1915–1916 and in 1930–1931.

Rainio mainly relied on medication to treat patients. She ordered drugs from Germany and Capetown, and asked and often received free samples from pharmaceutical companies. The SWA administration supplied quinine and Salvarsan, both of which were used in great quantities. The 1930s saw the introduction of insulin, still expensive and rare, and sulfa drugs, the first efficient broad-spectrum antibacterial family of drugs. Onandjokwe also played a role in implementing preventive measures. The staff vaccinated against smallpox and influenza, isolated lepers and TB patients and were affected by administration-imposed quarantines and disinfection campaigns.

Some diseases were more obviously political than others. During the interwar period, there was an evident correlation between the increase of labor migration on the one hand and an upsurge in VD and TB cases on the other hand. This explains why the administration willingly subsidised the treatment of these diseases at Onandjokwe. Leprosy also became a political issue, as the administration forbade the Finns to treat lepers coming from the Angolan side of the border. Rainio found this restriction hard to live with, for both humanitarian and public health reasons.

Melander’s arrival in 1932 heightened the relative importance of surgery at Onandjokwe. Rainio, who had no specialist surgical training, was reluctant to undertake major operations. This was a constant source of anxiety for her, and she started stressing early on that her successor must have a thorough education in surgery. Melander and Soini indeed took pains to acquire surgical skills before coming to Owambo. In the late 1930s and the 1940s, surgical activities were further boosted by the new operation room, as well as by the fact that some of the new nurses had experience of working in an operation room, and by an obliging district surgeon who could be consulted and asked to partake operations.

Making a Difference

In a 2014 article, Catharina Nord compared the outlook of Onandjokwe Hospital and Oshakati State Hospital (1966). The latter came into being within a short period of time as the result of a strategic and political decision. It was constructed from pre-fabricated elements imported from South Africa, and made no concessions to local customs or architectural traditions. Onandjokwe, on the other hand, was constructed mainly of local materials, and was a hybrid building that mixed features from Europe and Ondonga. My review of the early history of Onandjokwe fully supports Nord’s view of the hybrid character of the hospital complex. Without the luxury of steady, plentiful resources, the hospital evolved gradually, and, as it were, organically. Chronic scarcity allowed for little top-down long-term planning and required a readiness to adapt to local circumstances.

The significance of the Finnish medical mission in general and the Onandjokwe hospital in particular is highlighted by the scarcity of healthcare provision in Owambo at the time. None of the other European doctors occasionally working in the region – the district surgeon, a doctor employed by the diamond company, an Anglican missionary doctor – had a hospital at their disposal. The closest hospitals were in Windhoek and Swakopmund, hundreds of kilometers away, and they excluded black patients. Onandjokwe was no doubt a pioneering venture. Whether it had an impact on the overall health of the population is more difficult to ascertain, given the complex nature of such questions and lack of reliable population statistics from the period. However, as Notkola and Siiskonen (2000) point out, it seems highly likely that the preventive measures carried out by the Finnish medical mission did contribute to the clear drop in mortality that became evident in the 1950s.

Bibliography

The Archive of the Finnish Missionary Society. The Finnish National Archive, Helsinki.

Digby, A., Diversity and Division in Medicine: Health Care in South African from the 1800s. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2006.

Hakosalo, H., Modest witness to modernization: Finland meets Ovamboland in mission doctor Selma Rainio’s family letters, 1921–32. Scandinavian Journal of History 40:3, 2015, 298–331.

Heikkilä, E. & M. Nurmi, Minä voin mennä! Ambomaan ensimmäinen lääkäri Selma Rainio 1873–1939. Helsinki: Suomen Lähestyseura, 2000.

McKittrick, M., To Dwell Secure: Generation, Christianity and Colonialism in Ovamboland. Oxford: James Currey, 2002.

Melander, A., Terveisiä Ambomaalta. Helsinki: WSOY, 1942.

Miettinen, K., On the Way to Whiteness: Christianization, Conflict and Change in Colonial Ovamboland, 1910–1965. Helsinki: SKS, 2005.

Nord, C., Healthcare and Warfare. Medical Space, Mission and Apartheid in Twentieth-Century Northern Namibia. Medical History 58:3, 2014, 422–46.

Notkola, V. & H. Siiskonen, Fertility, Mortality and Migration in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Ovamboland in North Namibia, 1925–90. Houndmills: Macmillan Press, 2000.

Rainio, S. et al., Suuren parantajan palveluksessa. Kuvauksia lääkärilähetystyöstä. Helsinki: Suomen Lähetysseura, 1922.

Rainio, S. et al., Etelän ristin alla. Kuvauksia lääkärilähetystyöstä Ambomaalla. Helsinki: Suomen Lähetysseura, 1923.

Soini, A., Lääkärinä hiekan ja palmujen maassa. Porvoo & Helsinki: Werner Söderström, 1953.

Vaughan, M., Curing their Ills: Colonial Power and African Illness. Standford University Press, 1991.

About the Author

Heini Hakosalo is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Oulu (Finland) and Adjunct Professor at the University of Turku (Finland). She specializes in the history of modern medicine and health and has undertaken historical research on brain sciences, medical education and tuberculosis control and care. Her present research project deals with the history of birth cohort studies.