Stories from South West Africa for Young Finnish Readers

Raita Merivirta

In October 1929, the Finnish missionary magazine for children, Lasten lähetyslehti (published between 1900–1954), published an advert on its back cover that highlighted how the publication did not simply cover topics “from Lahti to Helsinki but from Owambo to China.” It was further explained that “Lasten lähetyslehti mediates information for Finnish children from faraway lands, primarily from Owambo and China.” As advertized, the magazine published stories and photographs from Finnish overseas missions. Owambo, as the region where the Finnish Missionary Society began its work, held a special place in the hearts of the magazine’s readers. The information mediated to Finnish children was produced by Finnish missionaries. The readers were offered reports and stories describing the environment, nature and animals of Owambo, as well as the people and their customs, habits and way of life. The reports also covered such topics as the churches and schools established in the area, as well as the experiences, successes and hardships encountered by the missionaries and their families in Owambo. In several issues there were also Q&A sections in which children could ask all sorts of questions, including the following selection: Do children in Owambo pick berries? Are there railways in Owambo? What crops are grown? Do African children play with dolls? What kind of social order does Owambo have? The questions were answered carefully and often illustrated with photographs or other pictures. The young Finnish readers were clearly very interested in knowing about everyday life in the south western corner of the African continent and the missionary magazine for children did its best to satisfy their curiosity. For youth, there was a separate magazine, Elämän Kevät (1907-1963). The Finnish Missionary Society also published fictional stories about life and adventures in South West Africa for young Finnish readers. Several youth novels, three of which are discussed herein, with Finnish missionaries as minor characters came out in the late 1950s and the 1960s. These works offered Christian alternatives to the more secular fiction of popular youth book series. The main publishing houses, such as WSOY and Otava, established separate departments for children’s and youth literature for the first time in the 1950s, and established book series for youth literature. WSOY’s Nuorten toivekirja series included both translated novels and Finnish originals and had a significant role in developing the model for youth literature in Finland. Adventure novels formed a sizeable part of the books published in the series aimed for both girls and boys. The youth novels that were brought out by the Finnish Missionary Society in the late 1950s and the 1960s were aimed at the same readership and perhaps therefore also included adventure stories.

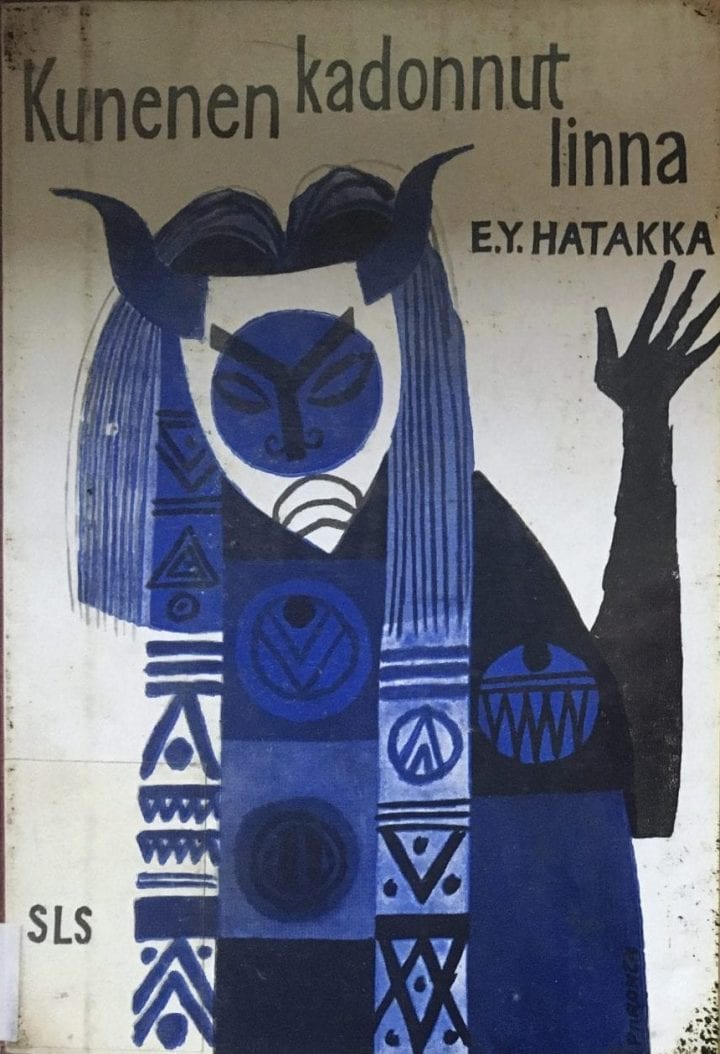

Pendapala proposes to Nahenda under the blooming acacia.

Sävy Vilkuna’s youth novel, Kun akaasia kukkii (When the Acacia Blooms), which was published in 1959, is a novel written for girls and is set in Owambo. Between 1962 and 1965, Vilkuna also edited the renamed and refashioned children’s missionary magazine first called Tuike: Lasten lähetyslehti (1955–1962) and then Totto: Tyttöjen ja poikien lähetyslehti (1963–1975). Kun akaasia kukkii is a fifty-page youth novella that focuses on a young Owambo woman named Niipindi. The blurb on the back of the novel states that the life of the young Owambo girl is depicted in a genuine and natural manner in the novella and that the difficulties the young girl experiences between the views of her home and tribe on the one hand, and the Christian way of thinking on the other, brings the whole young Owambo nation close to Finnish readers. As with the children’s missionary magazine, the purpose of the novella is educational: to mediate information for young Finnish readers about both the life of the Aawambo people and the work the Finnish missionaries were undertaking in the region. What, then, is the mediated story told by Vilkuna?

Kun akaasia kukkii begins by depicting the everyday life of Niipindi in a family that consists of her father, her mother, her father’s two other wives and her brothers and sisters. When the parents leave home for a shop that is a half-day’s journey away, Niipindi is left in charge of some of her siblings. Vilkuna writes of the practical arrangements made for the trip: the chores the children were asked to perform, the weather, the coming rains and other details. The two main plot strands – Niipindi’s upcoming arranged marriage and her resistance to it, and Niipindi’s secret interest in Christianity – are intertwined. Niipindi’s uncle Efraim has converted to Christianity and has told the family about his faith and the Christian God, much to the annoyance of the children’s father. This has raised the interest of Niipindi and her sisters, but their father has forbidden them to visit a church as he fears the wrath of the spirits. But what really makes Niipindi worried is her father’s plan to marry her off to Asheeke, a rich, older man to whom she would be a fourth wife. Niipindi is afraid that she would be bullied by the other wives. She thinks longingly about a young man, Angula, who left her village over a year previously in order to receive an education and to earn money. She imagines him returning home one day when the acacia is in bloom. She hatches a plan and escapes to her uncle’s house, where Efraim helps her and escorts her to a mission where she is safe. Over time, Niipindi converts to Christianity and learns to read and write. When her father and Asheeke arrive at the mission with a group of young warriors to catch Niipindi and take her back home, the Finnish missionary intervenes and leads a discussion with the parties involved. Niipindi, who chooses to stay at the mission, is disowned by her father. A couple of years later, Niipindi is still at the mission when a group of young men, Angula among them, return from the south. He is ill, but Niipindi nurses him back to health. It turns out that Angula began to learn about Christianity whilst he was away. Both Niipindi and Angula are baptized in the mission and take the names Nahenda and Pendapala respectively. They make plans to marry and to study and to become a nurse and a teacher and to do God’s work together. The novel ends with the onset of a new spring; a time when the acacias are in bloom.

Vilkuna’s novel has a very conventional plot and is in many ways a typical missionary story. However, what is significant is that the story focuses on a young, independent Owambo woman. Though she is young and under tremendous pressure, she takes matters into her own hands and takes charge of her own destiny. She chooses her own faith, occupation and husband, even when this means going against her family and traditions. As this is a missionary novel, Niipindi is helped by her Christian uncle as well as white Finnish missionaries and it is frequently explained to her that the Christian God guides those who seek him. Yet, she is also strong-willed and makes her own decisions. Furthermore, the novel not only introduces a young heroine from South West Africa to its young readers, but also describes the region’s daily life to them, thus truly bringing, as the blurb advertizes, “the young Owambo nation close” to Finnish readers.

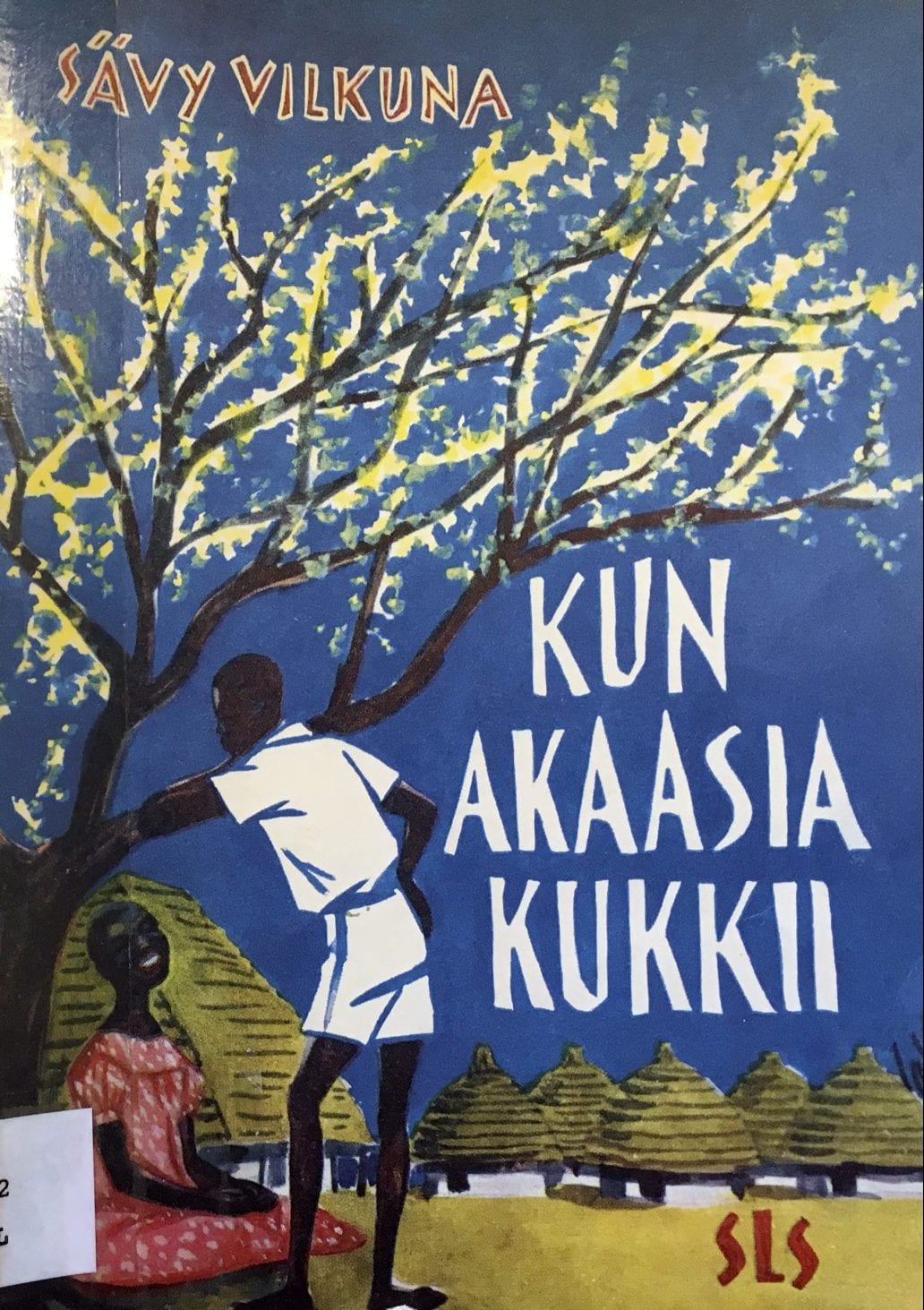

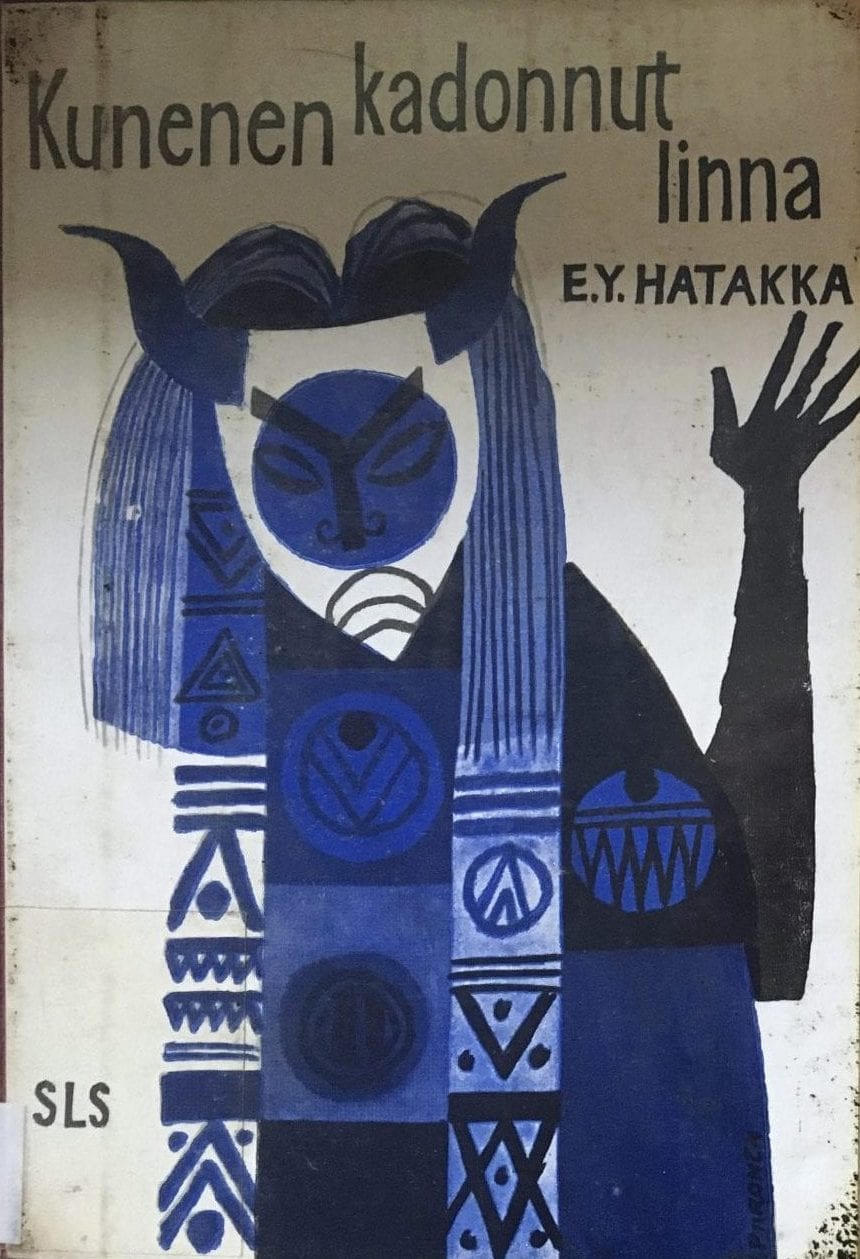

While Vilkuna’s novel focuses on the life of a young woman, Eero Hatakka and Pauli Laukkanen, who both worked for years as missionaries in South West Africa, wrote about – and for – somewhat younger boys. Hatakka’s Kunenen kadonnut linna (The Lost Castle of Kunene, 1958) is a straightforward adventure story set mostly in southern Angola, with Owambo as the starting point. The adventurers are a young Owambo servant boy named Kapija and a young Finnish boy Pekka, who both accompany a Finnish doctor, Eki Saunio, across the border to Angola in his search for a lost castle near the river Kunene. The boys’ job is to act as interpreters: Kapija speaks a little of the local language across the border, whereas Pekka speaks Kapija’s native language and can interpret for Eki. After several days spent looking for the castle, the party finds first a slab of rock with carvings and a map that leads them to their objective, which turns out to be a huge ring of stones. While Kapija returns home on foot a day earlier in order to take his family’s ox back home, Pekka and Eki stay behind to examine the castle. However, they are captured by a sorcerer and his men for entering sacred ground. They find a way to escape but are captured again. They are saved from being buried alive by Kilpola (Pekka’s father), Kapija and a German professor, who come to the rescue in a small plane.

In Kunenen kadonnut linna, the adventurers Eki, Pekka and Kapija search for a lost castle near the river Kunene, where they encounter a scary sorcerer.

The novel emphasizes the difference between the locals of Owambo and southern Angola, as well as between Christian and non-Christian areas and people in a stereotypical and prejudiced way. This is presumably done to foreground the positive effect of missionary work in the area, and puts white Finnish explorers/scientists/missionaries and their loyal native friend and helper at the center of this very typically colonial-style and in many ways problematic adventure novel. The (South West) Africa of Hatakka’s novel is an imaginary space, despite the authentic place names and descriptions of the local environment. The particular setting is used more as a means to entertain and tell a story about adventurous Finns overseas and their efforts to modernize the region than to convey information about everyday life in Owambo and southern Angola.

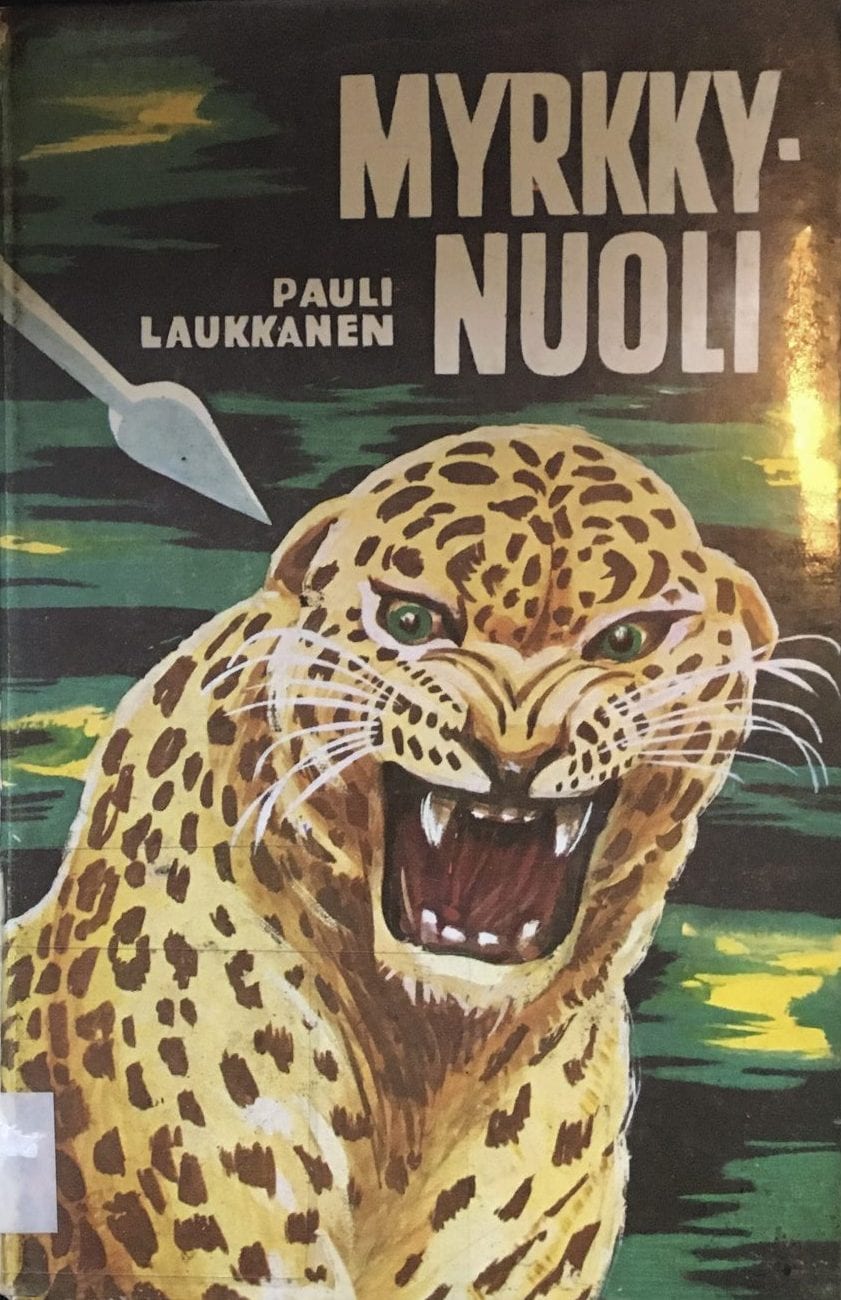

In contrast to Kunenen kadonnut linna, Pauli Laukkanen’s first youth novel, Myrkkynuoli (Poison Arrow), which was published in 1962, focuses on South West African characters rather than Finns. Laukkanen worked for several years as a missionary in South West Africa and authored two novels for youths that were set in the areas he knew well. On its back cover, Myrkkynuoli is advertized as an authentic account of contemporary Africa and as “an excellent guide to the mysterious world of the Bushmen” (the San people), the authenticity of the tale being guaranteed by his spending years among the locals. Myrkkynuoli’s main characters are an adolescent Bushman/San boy Kafita and his adult friend Kondo. The latter is a skilful hunter who gets into trouble with Shimbungu, a powerful sorcerer. In the beginning of the novel, the head of Kafita’s tribe, the Old Wise Man, orders all the men to gather around his fire and states that someone had neglected to produce the holy smoke of peace on their ancestors’ burial ground during the third full moon. Therefore, one of the neglected ancestors of this man had become angered and had begun wandering around in the guise of the leopard Long Whiskers. Since the tribe no longer had a sorcerer, they had to rely on the neighboring tribe’s sorcerer to find out who was the guilty party. The neighbors, who are referred to as being long-legged, are the Aawambo. Their sorcerer, Shimbungu, is the most famous and feared man in the vicinity, as he is able to communicate with spirits. The spirits of ancestors order him to dispense justice and it is to him that the Kafita tribe now turns. The spirits tell Shimbungu that Kafita’s friend, Konda, whom the sorcerer already dislikes due to a previous misunderstanding about a hunt, is guilty. The only way for Konda to save his life now is if Long Whiskers dies before the next full moon. Konda himself does not fully believe in the sorcerer and his powers, for he has been told about the Christian God, and has even shared his knowledge with Kafita, who has also become curious.

The leopard Long Whiskers is killed by the young Kafita, who thus proves his skills as a hunter and is given a poison arrow as reward.

Kafita has previously pondered what will be necessary in order for him to be allowed to use poison arrows like the grown-up men of his tribe. He concludes that he will need to do something valiant and thinks that hunting down Long Whiskers might be just the thing. He secretly helps to free Konda, who is being imprisoned in the sorcerer’s abode, and together they go after the leopard. They spend some time with missionaries, one of whom urges Konda to remember that Long Whiskers is just an unusually clever beast, not an ancestral spirit. Eventually, and somewhat unexpectedly, they run into Long Whiskers. They wait for the right moment, then Konda shoots several arrows at the leopard, which consequently attacks. The big cat mauls Konda and he is only saved by Kafita, who shoots an arrow and hits the leopard in the head. The missionaries help to heal Konda. Thus, he escapes the punishment ordered by the sorcerer, which enrages Shimbungu. Kafita is given a poison arrow as a reward by the Wise Old Man and is thus accepted among the hunters of the tribe.

Myrkkynuoli, Kafita’s coming-of-age tale, is an adventure story, like Kunenen kadonnut linna, which pits heroes against a powerful sorcerer. However, Laukkanen’s novel is much more attentive to local customs, way of life (including food, cooking methods, hunting, beliefs), environment and animals. As suggested in the blurb, it aims to introduce the world of the Bushmen/San to young Finnish readers, while also endeavoring to tell an engrossing adventure story that is able to capture the interest of the youthful readers.

Published by the Finnish Missionary Society, all of these youth novels advocate missionary work as a progressive and civilizing force in the area and are often patronizing towards South West Africans. However, all these novels also have very relatable and likeable young South West African protagonists with whom the reader is able to sympathize and who act as guides in a region foreign to the readers. Thus, while the novels may have emphasized and also helped to consolidate some differences at the time of their publication, they also levelled others between South West African and Finnish youths, crossing cultural boundaries and bringing Owambo and its people closer to young Finnish readers on an emotional level.

Bibliography

Hatakka, E., Kunenen kadonnut linna. Helsinki: Suomen lähetysseura, 1958.

Lasten lähetyslehti. 1929.

Laukkanen, P., Myrkkynuoli. Helsinki: Suomen lähetysseura, 1962.

Vilkuna, S., Kun akaasia kukkii. Helsinki: Suomen lähetysseura, 1959.

About the Author

Raita Merivirta is an Academy of Finland Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of European and World History, the University of Turku. She holds the title of Docent in English Philology, especially postcolonial literary and cultural studies, and has published on Indian-English literature, India on film, as well as Irish and Northern Irish cinema and history. Her current research project deals with colonialist discourse in Finnish children’s literature.