The Impact of Finnish Missionaries on Traditional Aawambo Dress

Loini Iizyenda

The change in dress brought by Finnish missionaries among the Aawambo people of Namibia is a crucial area that needs to be addressed when discussing Aawambo cultural identity. The beginning of Finnish missionary activities in Owambo from 1870 was one of the instrumental agents in the alteration of Aawambo traditional dress. The missionaries were from a different culture with their own distinctive dress code and values which defined them. Through contact with these missionaries, and partly with European traders, the cultural dress of the Aawambo changed not only in design but also in the materials used.

The pre-colonial costume of the Aawambo people was complex and fascinating, as it communicated information about a wearer’s life and social status. The basic costume of the Aawambo people originally consisted of a leather loincloth, girdle and ornaments made from objects, such as oyster shell, reeds, ivory buttons etc. The transition away from this traditional dress occurred as a direct result of the imposition of the missionaries’ values. This trend greatly affected the genuine representational meanings of the cultural identity and lifestyle of the clothing worn by the Aawambo people.

This chapter explores the costumes worn by the Aawambo people before missionary influence, with a focus on the basic dress for women. It will also examine the tactics and doctrine used by the missionaries to advocate for a change in the way the local people were attired.

The Traditional Attire of the Aawambo People in the Pre-Colonial Era

According to A. D. Symonds, the Aawambo are a group of Bantu people found in north-central Namibia. There are eight Bantu sub-ethnic groups and all were initially agriculturist. Their basic clothing and household utensils depended on what was available to them in their surroundings. According to V. Shigwedha, the “Aawambo were known to be highly artistic and skillful people’’. They were skilled in leather tanning, metalwork, pottery, basketry, beadwork and woodcarving. These crafts were used to produce their clothing and adornments.

The costumes worn by the Aawambo were complex as they reflected specific information related to clan, gender and age group, as well as social and marital status. A traditional costume consisted of cattle or goat hide and ornaments created by ironsmiths, incorporating ivory buttons, oyster shells and ostrich eggshell. Shilongo describes how “the initial clothes of the Aawambo, in particular the women”, were “basically pieces of tiny leather from cattle that was meant to cover and conceal genital parts”.

Clothing for women consisted of a leather apron called an eteta, which was tied to the body with a belt that was also made from cattle hide called ekwamo. H. Tonjes describes how the belt was wound around the hips several times to serve as a pocket. The length and manner in which the leather cloth was hung on the body was determined by the person’s age, as well as their marital and social status. Younger girls, for example, wore the shorter eteta, which only covered the frontal parts of the genitalia. The eteta was longer for married women and also covered the backside area.

Coiffures and beaded ornaments also played a significant role in communicating information about an individual among the Aawambo. Beads were not only worn for decoration, beauty and status, but also served a ritual purpose. L. T. Nampala and V. Shigwedha discuss how some beads were also believed to serve as protective talismans, while others were meant to attract fortune and luck. Thus, various types of beads were used in a woman’s attire, which demonstrated her development from girlhood to womanhood.

Nampala and Shigwedha define the beads as “locally produced or found such as nickel beads, iron beads, ostrich eggshell beads, ivory buttons, and seed or grass beads from local plants. Others were obtained through trading such as glass beads and oyster shell beads”. As mentioned earlier, hairstyles also complemented the costume in order to visually express the wearer’s status. According to Shigwedha, hairstyles also reflected the wearer’s sex, age and class.

Girls from the age of six began to plait their hair in preparation for puberty. As Nampala and Shigwedha show, the first hairstyle was called onyiki, which consisted of plaits decorated with seeds from the local plum tree. This onyiki hairstyle was later replaced by the oshilendathingo, whereby the hair was plaited with animal sinews that were twined to form several hornlike structures on the head. This hairstyle was for girls between 11 and 12 years of age.

Girls undergoing the puberty rite ceremony called efundula wore a new hairstyle. Coiffures for the efundula depended upon the sub-ethnic group one belonged to. The hairstyle changed once a woman had married in order to communicate her elevated status. The change of dress brought by foreign cultural interference caused cultural information and a dilution of skills. The traditional dress was a symbolic expression that encompassed one’s lifestyle, role, skills and beliefs. A woman had to be precise in the way she dressed and this was also dependent upon her stage of life and status.

Young Ovambo women in precolonial traditional clothing and hairstyle. National Archives of Namibia (undated).

Finnish Missionaries and their Influence on the Traditional Attire of the Aawambo

Finnish missionaries were agents who imposed European dress styles on the Aawambo people through their mission work. As stated by Shigwedha, “the role of different missionary denominations in Owamboland since 1870, is crucial in understanding the circumstances that implemented the dramatic transformation of traditional fashion since the turn of the twentieth century.” The change in attire was initially instigated by the missionaries, who regarded the traditional leather dress of the Aawambo to be an expression of paganism. The missionaries felt the need to expose the local people to “appropriate clothing”.

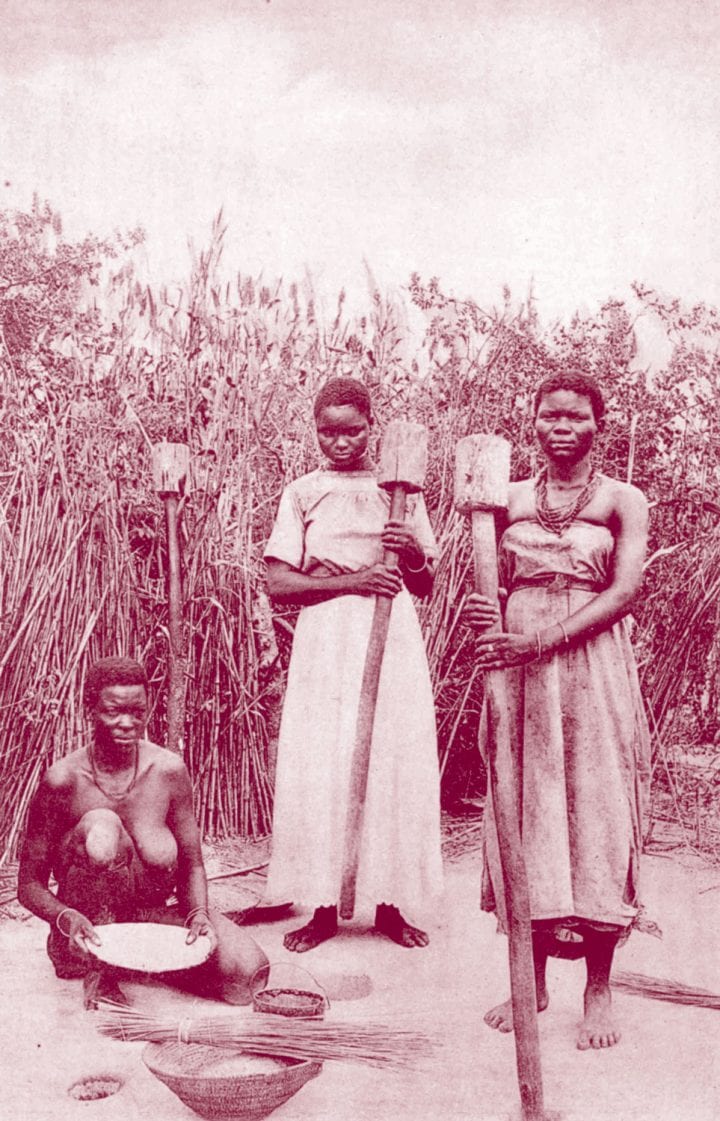

Young Ovambo women pounding mahangu, wearing early missionary style clothing. National Archives of Namibia (undated).

The strategies used by the missionaries to ensure that the Aawambo wore “appropriate clothing” concentrated on clothing donations, cotton projects and sewing classes. According to Sabina David “ the first converts who also played a major role in influencing other people in the community to abandon traditional costumes were not allowed to smear their bodies with the red ochre [Olukula] and were advised not to dress in traditional outfits when attending church services, instead they had to wear cotton clothes.” Changing the traditional dress of the Aawambo also entailed altering the material and skills used in the creation of this new dress code.

The limited access to materials in the region may have led the missionaries to establish their own cotton plantation. According to Nampala and Shigwedha, the Finns discovered that “cotton could be grown in Ovamboland if watered during the dry season. Cotton tools, spinning-wheels and hand looms were sent to Owamboland from Finland”. Hence, a cotton project was implemented with the objective of training the Aawambo people to make their own fabrics for clothes. According to Tonjes, the project proved futile due to the costs involved, as well as the local weather conditions.

Despite the failure of the cotton project, missionaries continued to emphasize the need for locals to change their attire by offering tailoring classes. The idea was that by teaching sewing skills to the locals, using donated cloth, locals would be able to imitate the missionaries’ idea of decent clothing. As Namapala and Shigwehda note, “Tailoring training did not stop as missionaries continued to receive cotton materials form Finland”. The acceptance of the dress code imposed by the missionaries acted as a proof of the commitment of the Aawambo to the Christian faith. Consequently, locals gradually abandoned their traditional dress, which relied on the local environment and traditional skills.

Tonjes clarifies this occurrence by stating that “many female societies [in Finland] have taken on part of this responsibility upon themselves by sending simple cotton cloth. It was also cheaper to import clothes than to produce them locally. The Christianized locals in Namibia became dependent on the imported clothes and cloth from Finland, which were distributed among the people. Sabina David informs us that “people eventually did away with traditional clothes and burned them. By doing so, they were persuaded to believe that they were abandoning paganism and evil objects for the righteousness of God the savior.”

The Modernized Traditional Dress of the Aawambo

The contemporary dress style of the Aawambo is identifiable by the striped cloth called Ondhelela, which is primarily a trade cloth used to make a gathered skirt or dress called Ohema dhontulo. The Ondhelela cloth has a background color of white, with either red, green, blue or black lines. Apart from the striped Ondhelela, locals could select from a wide variation of cloths. The cloths have been well received as they are able to absorb the traditional dye, which was formerly used on the leather. The practicality of the cloth led to its popularity. Compared to the preparation of the pre-colonial costume, which required the leather to be tanned or to undertake intensive beadwork, the use of imported materials from Europe was more time and cost efficient.

The Ondhelela or Ohema dhontulo is presently worn by every woman, irrespective of age or status at every traditional ceremony (weddings, puberty rites etc.). The dress is further accessorized with ornaments, such as beaded neckpieces, waistbands, girdles and bracelets. The absence of differentiation in the Ondhelela skirt or dress weakens the symbolic connotations that were once associated with each component of the traditional attire.

J. B. Okapilike and K. L. Nwadialor argue that the missionaries had a negative influence on local people and their cultural dress because “most European missionaries were unable to emancipate themselves from the cultural, emotional and social frame in which they were used to live and express; they tended to identify Christianity with European civilization.” In agreement with the above statement, I argue that it was unethical and demoralizing for the pioneering missionaries to teach the locals that their “traditional costumes and ornaments” were heathen objects.

The locals were dressed according to what was available to them in their native environment, and according to the skills that they had developed based on traditional practises. These skills and ornaments were important, as they defined who the people were, as well as their roles in their specific ethnic societies. Missionaries should not have emphasized the need to change the locals’ cultural attire in order to represent their conversion to Christianity. They should have rather focused on simply delivering the Christian message to the people.

Currently, more effort is needed to maintain Aawambo identity due to the imposition of an imported dress code. The imported European dress code and material serves a different function and skill, which has no similarity or relevance to Aawambo cultural beliefs or lifestyle. Other outcomes related to the introduction of imported Eurocentric material and clothing includes the loss of the indigenous knowledge that was expressed in the original dress. Traditional craft skills also remain underdeveloped due to them being substituted by acquired skills from Europe.

Bibliography

Nampala, L. T. & Shigwedha, V., Aawambo Kingdoms, History and Cultural Change: Perspective from Northern Namibia. Basel: P. Shlettwein Publishing, 2006.

Miettinen, K., On way to Whiteness – Christianization, conflict and change in colonial Ovamboland, 1910–1965. Helsinki, Finland: Bibliotheca Historica, 2005.

Okapilike C. J. B & K. L Nwadialor, The missionary twist in the development of the IGBO identity: the dialectics of change and continuity, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka. 2015. https:// www.researchgate.net/publications/276270485

Tonjes, H., Ovamboland Country: People Mission with particular reference to the largest tribe, the Kwanayama. Namibia Scientific Society, 1996.

Symonds, A. D., A journey through Uukwaaluudhi history. Namibia Community Based Tourism Assistance trust, 2009.

Shigwedha, V., Pre-colonial costumes of the Aawambo; Significant Changes under Colonialism and Construction of Post-Colonial Identity. Windhoek, Namibia: University of Namibia, 2004.

Interviews

Shilongo Andreas Uukule, interviewed by Vilho Shigwedha, 11 October 2002 Uukwanambwa, Ondonga.

Sabina David, interviewed by Vilho Shigwedha, 25 February 2002, UNAM Boardroom, Northern Campus.

About the Author

Loini Iizyenda is a fashion and textile lecturer at the University of Namibia, with an MA in Sustainability in Fashion. Her research area focuses on the precolonial and postcolonial traditional costumes of the Aawambo people. She is also studying product development explorations with sustainable design strategies.