The Finnish Mission’s Relationship to Anglicans and Roman Catholics in South West Africa, 1919–1937

Kati Kemppainen

Until World War I, the monopoly of the mission work in Namibia (then German South West Africa) was held by two Lutheran missions: The Rhenish Missionary Society and the Finnish Missionary Society. The German regime practised a very anti-Catholic mission policy. Thus, The Roman Catholic mission had very little room to operate in the region. The same applied to the Anglican Church: as long as the area was ruled by Germany, the Church of England could not launch its own mission activities there.

However, an increase in the number of Roman Catholic missionaries towards the end of the nineteenth century put pressure on the German regime to mitigate its anti-Catholic legislation. The change in the restrictive policy occurred after the Herero Uprising of 1904–1907, which caused tremendous societal change in the country in general. Until this event, Catholic missionaries had had to restrict their activities to areas inhabited by European migrants, mostly in Windhoek and Swakopmund. After 1907 they were allowed to establish mission stations among the native population, although still with some restrictions imposed by the German colonialists. The Roman Catholic missionaries were very interested in Owambo and Okavango, but the former region remained closed to them. The mission work carried out in Owambo was strongly guarded by German officers and also by the Finnish missionaries. In Okavango, the Roman Carholic mission gained a permanent foothold in the 1910s.

As a result of World War I, the mission situation changed dramatically. Germany lost it colonies and the mandate of South West Africa was given to South Africa by the League of Nations. An important change took place when the Church of England was allowed to start its own mission: the Damaraland Diocese was established, with its first bishop being Nelson Fogarty. The mission work was entrusted to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, which advocated the High Church form of Anglicanism.

The new South African regime ended the monopoly of the Lutheran mission in Owambo. Since the area was heavily populated, other denominations were also motivated to begin missionary work in this region. Moreover, there were locals who had converted to either Roman Catholicism or Anglicanism during their working periods in Hereroland. This was one more argument used to pressure the government to open Owambo to other denominations. In July 1924 the government announced a territorial tribal division: the Finnish Mission was to keep Ondonga, Anglicans were allowed to settle in Oukwanyama and Roman Catholics were granted Uukwambi and Ongandjera. In addition, the Finns were allowed to keep the mission stations and schools that they had already established on the other tribal areas. However, expansion was limited to Ondonga.

These developments shocked the Finns deeply, because only the previous year had they been assured that their monopoly would remain intact in Owambo. Both the individual missionaries and the leadership of the society considered this as an insult against their status, legacy and long working history in Owambo. They might be able to accept the arrival of other mission societies, but not the restrictions that were put on their work and plans. As a result, the attitudes of the Finns grew more anti-British and more pro-Germany. They felt they had been deceived by the colonial powers, as they practically saw Owambo as their own property.

The Finnish Missionary Society engaged in a variety of tactics to advocate their agenda. The crisis should be solved, in their opinion, in a way that benefitted them best. The missionaries, led by Reinhold Rautanen, tried to persuade the tribal kings not to allow anyone else to settle on their territory. This was not a very successful initiative. Consquently, they had to abide to the decree to reinforce their existing work among the tribes that were handed over to other missions.

The management of the Finnish Missionary Society also undertook a serious campaign to guarantee its status in Owambo. The indifferent attitudes and strategies used by Roman Catholic missionaries did not surprise the Finns, but the arrival of the Anglicans was far more hard for them to understand since they were also Protestants, and they had not anticipated that they would act this way. There was a so-called “missionary comity” established within the international Protestant missionary movement, which was supposed to prevent missionaries from entering areas that were already occupied by other Protestant missions.

Thus, the arrival of Anglicans infuriated the mission director of the Finnish Missionary Society, Rev. Matti Tarkkanen. He immediately contacted Bishop Fogarty, the head of the Anglican missionary society and the Archbishop of Cape Town. Since these contacts were unsuccessful, he turned to the National Lutheran Council of America, which was known to be strictly confessional. The secretary of the Council, Rev. John A. Morehead, was eager to defend the freedom of a Lutheran mission when it was endangered, and therefore informed the Lutheran world about the incident in Owambo.

Tarkkanen also contacted the International Missionary Council, whose chairman, John R. Mott, symphatized with the Finns. The Archbisop of Canterbury, Randall Davidson, was contacted via the Archbishop of Sweden, Nathan Söderblom, who was an influential ecumenian of the time. Understandably, the Archbishop of Canterbury was not keen to act, but showed only a polite and reserved attitude. The World Alliance in Finland was keen to help, but not even the skilled diplomacy of Rev. Aleksi Lehtonen had any positive results. The Anglican counterpart pleaded to the sovereignity of the Bishop of Damaraland over his diocese.

During his inspection tour of Owambo, Tarkkanen tried to influence Gysbert R. Hofmeyr, the administrator of South West Africa, but again without any results. The meeting between Bishop Fogarty and Tarkkanen was a total failure, and the crisis in Owambo culminated in a personal power struggle between those two individuals. Apparently, the arrival of Roman Catholics was not deemed to be as important as the arrival of Anglicans. The situation in Owambo was broadly reported in Finland by the major church magazine Kotimaa, as well as by mission magazines.

Finnish missionaries did not blindly obey the rule of tribal territorial divisions, even though they normally tended to emphasize their loyalty to the local colonial government. Tarkkanen encouraged his missionaries to intentionally overlook these restrictions. Thus, the situation in Owambo escalated, as all the parties were disssatisfied with the restrictions. Since the colonial government was also aware of the dire relationship between the missions, it was predictable that they would try to abolish territorial tribal divisions in 1926. The era of total missionary freedom now commenced, but not even this satisfied the Finns. Their desire to achieve the freedom to work did not, however, extend to other missions.

The immediate consequence of the freedom to work was positive for the Finns. They were allowed to continue using their existing resources, whilst other missions were unable to take advantage of these opportunities and to expand their work. What, however, was the long-term impact of missionary freedom? The situation in Owambo developed quite interestingly, since each mission had distinctive advantages. According to the Finns, the Roman Catholic mission possessed the best material resources and had sufficient levels of staffing and solid finances. In theory, the Anglican mission was supported by the government, but apparently this did not materialize in practise. The Finns had gained a solid foothold by the 1920s, helped by their knowledge of the local culture and language.

The other missions did not become a real threat to the work of the Finnish Missionary Society in Owambo. The Anglican mission only remained in Oukwanyama and was minor in scale. They developed a cordial relationship with the Lutheran Finns and were able to co-exist in the area. This was not the case with the Roman Catholic mission. They mostly concentrated their efforts among the Ombalantu and Uukwambi tribes, but were met with animosity. The Finns kept an eye on the Catholic mission and accused them of suspicious work strategies, such as having a below-standard level of baptisms and trying to entice new pupils with the prospect of receiving clothes and sugar. They were also accused of neglecting Christian education and being far too tolerant of supposedly pagan practises. Rumors also circulated about the doubtful morality of Roman Catholic missionaries and their liberal attitude towards alcohol. Actual personal contact between Roman Catholics and Finnish missionaries, however, was rare.

The Finnish missionaries were keen to find out news about their rivals, but they were also clearly influenced by speculation and rumors. When it served their own aspirations, the threat of other missions was often exaggerated. This occurred when there was a need for extra funding for some purpose. Tarkkanen had to remind the Finnish missionaries that competition alone could not justify the expansion of their work.

In 1929 the Finnish missionaries expanded their work into Kavango, where the Roman Catholic missionaries had already established their position. The Finnish missionary work was limited to the Kwangali tribe, whereas the Roman Catholics were influential in the eastern part of Kavango. Interestingly, the expansion of missionary work into Kavango was not unanimously approved of by all the Finns in Owambo. Opposition centered on the argument that they were now acting in the same way as rival Christian confessions had behaved in Owambo only a few years earlier: they were now the intruders. The most eager spokesmen for moving into Kavango were the missionaries Aatu Järvinen and Tarkkanen, who did not find the situation to be paradoxical at all. In the 1930s, the mission work in Kavango remained rather modest, which was not reported truthfully in mission magazines nor in annual reports.

The arrival of other missions had clearly motivated the Finns. Now they had to pay more attention to the content and quality of their own work. The geographical expansion of their work and their focus on the teaching of Lutheran doctine was a direct outcome of the arrival of the Roman Catholic mission. The Finns thought that their Christian mission would be a failure if they were to lose their position in Owambo to the Roman Catholics. The confessional competition culminated in the middle of the 1930s, when a controversy over school sites broke out and even the government had to interfere. Consequently, cooperation between the Lutheran and Roman Catholic missions broke down completely due to insurmountable doctrinal differences.

The role of local people remained minor in this confessional competition: the Finns were not very interested in the reactions of local tribal kings. This attitude shifted greatly as they seemed to favor the party that would provide them with most economic and political benefits. The local authorities also seemed to favor the Finnish mission. The same tendency can be found in the upper level of government, even though these links had to remain indirect. The Finns were extremely sensitive to the attitudes and reactions of local officials. Despite being critical, the Finns were favored by the local population in most cases at the expense of other missionaries. At this time, the general attitude of the Finnish missionaries was quite suspicious towards local officials. The missionary Valde Kivinen was able to confide in Charles Hahn, the local officer in charge. Kivinen knew the best methods of practising diplomacy with him. He managed to maintain the confidence of the authorities towards the Finns. He did this by emphasizing the importance of acting in strict accordance with the regulations. He avoided acting as arbitrarily as the Roman Catholic missionaries. He did his best to minimize the work opportunities of confessional rivals among the western tribes.

The relationship between the Lutheran and Roman Catholic missions remained very tense during these years, while the mutual understanding between the Finnish and the Anglican missions increased in the 1930s. Intercommunion between the Church of England and the Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Church was established in 1934. This had a surprising consequence on mission work in the region. When the new mission director, Uno Paunu, undertook his inspection tour to Owambo in 1937, he met the Anglican Bishop C. C. Watts. Bishop Watts expressed his willingness to withdraw the Anglican mission from Owambo and to leave the whole area to the Finnish mission. The positive progress of the Finnish-Anglican relationship did not occur because of a new doctrinal convergence between the churches. Instead it had much more to do with how the respective leaders of the two confessions interacted with each other and made decisions. Director Paunu and Bishop Watts had an opportunity to forge a mutual understanding, because their relationship was devoid of personal tension. This had not been the case with Tarkkanen and Fogarty. Similarly, Paunu and Watts were able to act in a considerably more diplomatic way than their predecessors.

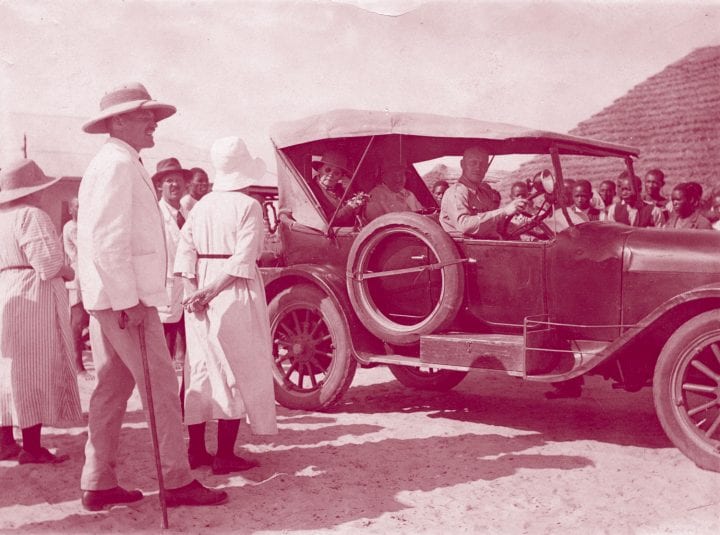

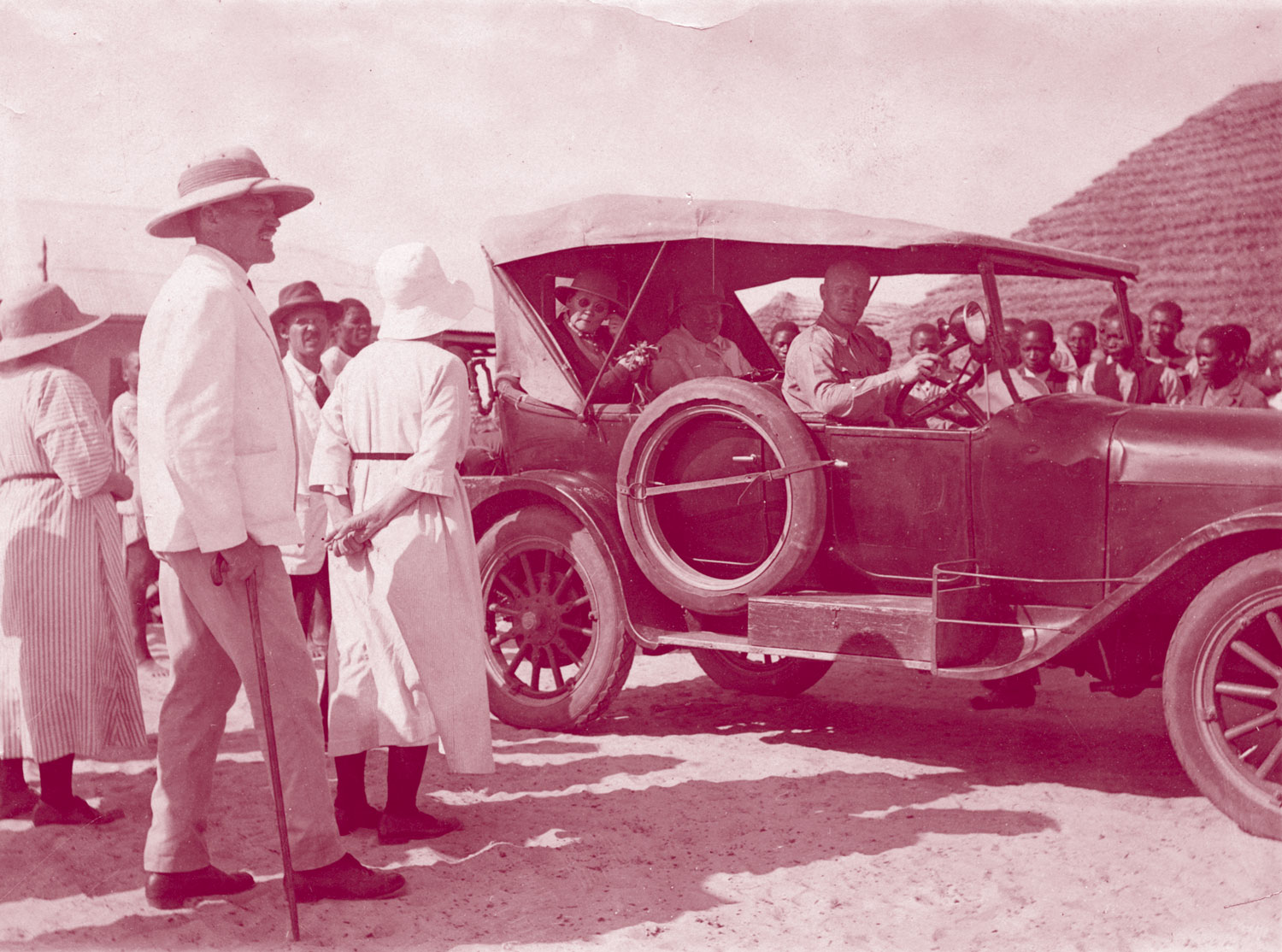

Finnish mission workers received a Hupmobile car in 1925. Matti Tarkkanen sitting in the back seat. The Finnish Heritage Agency.

About the Author

Kati Kemppainen, PhD (Theology) is a senior theological advisor at Felm. She is a specialist on mission history, and currently also works in the fields of missiology, ecumenism and contextual theologies.