A Cinderella of Europe: Understanding the political history of Belarus

Andrej Kotljarchuk,

Ph.D., Associate Professor,

School of Historical and Contemporary Studies, Södertörn University,

Sweden

Belarus remains one of the most little-known countries in Europe. There are several reasons for this. The primary one can be ascribed to the fact that in modern times Belarus did not exist as a political entity. During this time Belarus had no sovereignty, being initially a province of Poland-Lithuania and the Russian Empire. The cold war contributed to the disappearance of Belarus from the Western political and academic discourses. Few scientific books about Belarus were published in the West prior 1991.[i] Despite the membership of the Belarusian SSR in the UN, Belarus was absorbed by the Soviet Union. Unlike neighboring Latvia and Lithuania, Belarus was not independent during the interwar period and had no large diaspora in the West after 1945. Therefore, the Belarusians often considered by Europeans as ‘white Russians’, a people without a tradition of the statehood, native language, culture and political history. For the first time Belarus appeared on first pages of international media in August 2020. The rigged elections after the long-term authoritarian rule by President Lukashenka led to mass protests across the country for the right to vote at free and fair elections. However, the lack of knowledge and skills gaps within Western academic communities regarding Belarus are obvious.

The Belarusian national movement was one of the latest in Europe that emerged after the first Russian revolution. The first political party, the Socialist Party Hramada was founded in Minsk in 1905. The first Belarusian-language newspaper was established in Vilna (Vilnius) in 1906. The first history of Belarus, written by a Belarusian writer in Belarusian, was printed in 1910.[ii] The first network of Belarusian-language schools was created only in 1916 in the German occupational zone. The first grammar of modern Belarusian language was printed in 1918. [iii] The First All-Belarusian Congress, which held in Minsk in December 1917 and gathered 1872 delegates from different regions, which proclaimed an autonomy of Belarus within Russia. However, the Congress was violently dispersed by Bolshevik military. In February 1918, the members of the Executive Committee of the Congress returned to Minsk. Here, an independence of Belarus was proclaimed on March 25, 1918. Until the end of 1919, the government of Belarusian Democratic republic (the BNR) co-existed with an alternative Communist government of the Socialist Soviet Republic of Belorussia (the SSRB) formed in Smolensk. The SSRB later became part of the Lithuanian–Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. In the end of 1919 the BNR government had to move to Vilnius and later to Hrodna. The diplomatic struggle BNR for the international recognition was one of most successful stories of the BNR. For example, Finland followed the political developments in Belarus;[iv] something that is neglected in recent Nordic studies.

Figure 1: The enamel sign of diplomatic mission of the BNR. 1919. Wikipedia, public domain.

In 1918 on the behalf of the BNR Mitrofan Dounar-Zapolski, the professor in history, wrote a book entitled The basis of Belarusian state individuality, which was published in English, German and French languages. He pointed out that a Belarusian statehood has deep historical roots in the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Ruthenia and Samogitia (the GDL). Dounar-Zapolski noted that the official language of the GDL was old Belarusian, not Lithuanian. He stressed the role of this medieval state in the formation of Belarusian ethnos. Indeed, the former borders of the Grand Duchy with Poland and Russia almost coincide with the ethnic borders between Belarusians and Russians in the east, Belarusians and Poles in the west, and Belarusians and Ukrainians in the south.[v]

Figure 2: “Självstyre för Vitryssland” [ Self-government for Belarus] – an article published in Finnish press, Åland, 15.08.1917.

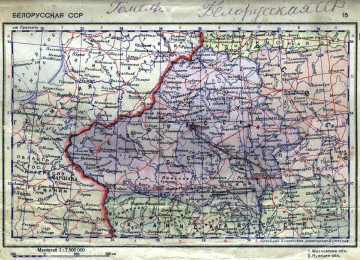

In 1921, the young Belarusian republic ceased to exist due to the capture of the whole Belarusian territory by Polish and Bolshevik forces. According to the 1921 Treaty of Riga, Belarus was divided between Soviet Russia and Poland. The Belarusian autonomy was developed on Soviet side with a capital in Minsk. In 1922 the Belarusian SSR become one of the founders of the Soviet Union. On the Polish side the Belarusians deprived the autonomy and minority rights. Under the Soviet rule Belarus enlarged its territory in 1924, 1926 and especially in 1939 after the Reunification of Western Belarus – an official term in Belarus of what happened with Eastern Poland after the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. The pact had the catastrophic consequences for the lands in the Baltic Sea region and led to massive deportations of the population of Western Belarus. However, the territory of Belarus (like in case of Ukraine and Lithuania) increased considerably, from 126,000 to 223,000 square kilometres.

Figure 3: Map of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1940 after the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. Wikipedia, public domain.

After World War II Belarus lost its two regions (Bialystok and Podlasie), which were ceased back to Poland. In post-war Soviet Union, Belarus considered, together with Estonia, to be one of the most developed republics. Moreover, unlike Estonia, Belarus had an image of the pro-Communist republic. The recent studies questioned this image and have shown the existence of strong dissident movement in Soviet Belarus.[vi] The first anti-Soviet rally in Belarus was held in 1988 in Minsk, at Kurapaty – the formerly secret extermination site established by the NKVD. On 27 July 1990, Belarus declared its national sovereignty, a key step toward independence from the Soviet Union. Around that time, Professor Stanislau Shushkevich became the chairman of the Supreme Soviet, the top leadership position in the country. On 8 December 1991, Shushkevich met with Boris Yeltsin of Russia and Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine in Belavezhskaya Forest in Western Belarus, to formally declare the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In 1991 the parliament declared that a correct name of the country in English and other European languages is Belarus (not Byelorussia or White Russia), the name, which is not related historically to Russia, but to Rus – a medieval state with its centre in Kyiv.[vii]

In 1994, the first democratic elections were held, and Alexander Lukashenka was elected president of Belarus. A year after taking office, Lukashenka won a controversial referendum that gave him the power to dissolve the parliament. In 1996, he won another referendum that dramatically increased his authoritarian power and allowed him to rule the country in authoritarian way for next decade. Therefore, one of the main aims of recent protest is to return the democratic constitution of 1994 and the national white-red-white flag, which was prohibited by Lukashenka in 1996.

[i] See: Vakar, Nicholas, Belorussia: the making of a nation: a case study, Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1956; Lubachko, Ivan S., Belorussia under Soviet rule 1917-1957, Univ. Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 1972.

[ii] Ластоўскі, Вацлаў, Кароткая гісторыя Беларусі, Вільня, 1910.

[iii] Michaluk, Dorota & Rudling, Per. A., “From the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to the Belarusian Democratic Republic: The Idea of Belarusian Statehood during the German Occupation of Belarusian Lands, 1915-1919”, The Journal of Belarusian Studies, 2014:7, 3–36.

[iv] See: ”Minsk skall bli huvudstad”, Syd Österbotten, 8.05, 1917; ”Självstyre för Vitryssland”, Åland, 15.08.1917;”Vitryska representantmötet förklaras upplöst”, Wasa-Posten, 03.01.1918;”Vitryska radan åter i Minsk”, Hufvudstadsbladet, 24.12.1919.

[v] Kotljarchuk, Andrej, “The tradition of Belarusian Statehood: a war for the past”, Contemporary Change in Belarus. Baltic and Eastern European Studies. Vol. 2. Södertörn University. 2004, 41–72.

[vi] Astrouskaya, Tatsiana, Cultural Dissent in Soviet Belarus (1968–1988). Intelligentsia, Samizdat and Nonconformist Discourses. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag 2019.

[vii] Закон Республікі Беларусь ”Аб назве рэспублікі Беларусь”: 19.09.1991 г. No. 1085-XII.

Email: andrej.kotljarchuk@sh.se

Expert article 2773