Nord Stream 2: Delayed but unstoppable

Katja Yafimava,

Dr., Senior Research Fellow,

Natural Gas Research Programme, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies,

The United Kingdom

Introduction

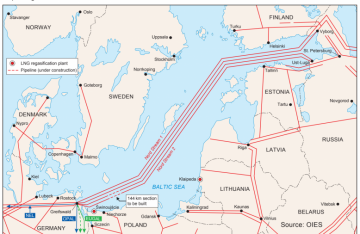

Nord Stream 2 (NS2) – an offshore gas pipeline system, consisting of two parallel pipelines connecting Russia and Germany and running (largely) in parallel to Nord Stream (NS) built in 2012 – is the final element of Russia’s transit diversification strategy, aimed at increased ability to export gas to Europe without excessive reliance on transit countries (Figure 1). Russia’s existing pipeline export capacity towards Europe (including Turkey) is estimated at ~230 bcma, thus being only marginally above the level of Russian gas exports to Europe in 2019, and of which only around one third does not involve transit. Once built, NS2 will increase this capacity by 55 bcma thus ensuring significant export flexibility. Although NS2 was scheduled to start flowing the gas at the end of 2019, multiple obstacles led to a delay. At the time of writing in September 2020, ~140 km of pipelines (108 km in the Danish exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and 32 km in the German EEZ), or ~6% of total combined length, remain to be built. This article overviews some of these obstacles and explains how they can be overcome.

Figure 1. NS and NS2 pipelines

Source: OIES

Danish permit

One of the most serious challenges to NS2 came from Denmark, which severely delayed its construction permit. It was only granted on 30 October 2019, two and a half years after the first application was made. In total, NS2 AG (a company established to build and operate NS2) made three applications to the Danish Energy Agency (DEA) in respect of three different routes:

- the original southern route (passing south of the Danish island of Bornholm in the Danish territorial sea, April 2017),

- the northern route (passing north of Bornholm in the Danish EEZ, August 2018),

- the amended southern route (passing south of Bornholm in the Danish EEZ, spring 2019).

In November 2017, the first application already being under consideration for six months, Denmark passed a law allowing for permits in respect of pipelines running through the Danish territorial sea to be rejected not only on environmental (as previously) but also on foreign/security policy grounds. This law appears to have been designed to allow Denmark more time to decide on the permit while waiting for a common EU position on NS2. (In October 2017 the European Commission initiated the process of amending the Gas Directive, as a result of which the German section of NS2 became subject to its provisions, when the amended Directive entered into force in May 2019.) In August 2018, witnessing no progress on its first application, NS2 AG applied for a permit in respect of the northern route (in respect of which a rejection could only be made on environmental grounds as it was not passing through Danish territorial sea). In spring 2019, having made no decision on either application, DEA asked NS2 AG to submit a third application, this time for an amended southern route, which would avoid passing through the Danish territorial sea. It was in respect of this route that the permit was granted in October 2019.

By the time the Danish permit was granted, construction of the Finnish, Swedish, Russian and (most of) German sections had been finalized. Construction of the Danish section (two lines of 147 km each) began on 4 December 2019 and was due to be completed by mid-January 2020. However, construction was halted on 21 December 2019 as Allseas (a Swiss company, providing pipelaying vessels and services for NS2 construction) suspended operations under threat of US sanctions (see next section). By this time, only around 108 km of pipelines remained to be laid in the Danish EEZ.

Allseas works suspension meant that other companies and vessels, not deterred by the threat of sanctions, would have to be found to finalize construction. It is understood that the two Russian vessels – Akademik Cherskiy and Fortuna – are technically capable of building the remaining section, albeit at a lower speed (~0.34-1 km/day) than Allseas vessels (~3 km/day). Akademik Cherskiy is equipped with dynamic positioning system (as Allseas vessels are) whereas Fortuna is an anchored-based vessel; in July 2020 DEA has amended its construction permit to confirm the usage of both types of vessels. At the time of writing, they were at the German ports of Mukran and Rostock respectively, within a day sailing to the NS2 construction site.

US sanctions threat

Although the US have been hostile towards NS2 from its inception, it initially refrained from taking any action against it. However, as the project progressed, on 2 August 2017 the US adopted the Countering American Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), which enabled the US President ‘in coordination with allies’ to impose sanctions on a person which knowingly, on or after 2 August 2017, ‘makes an investment […] or sells, leases, or provides’ to Russia ‘goods, services, technology, information, or support’ (of defined value) ‘for the construction of Russian energy export pipelines’. The US State Department guidance, issued on 31 October 2017, specified that investments and loan agreements made prior to 2 August 2017 would not be subject to sanctions. Notably, NS2 pipelaying vessels have been leased, pipes ordered, and financing agreed (and partly executed) prior to that date.

On 15 July 2020 the US State Department amended the guidance, by expanding the focus of implementation of CAATSA to include NS2 and deleting the sections saying that investments and loan agreements made prior to 2 August 2017 would not be subject to sanctions. Although the amended guidance confirmed that sanctions will not be imposed in respect of investment and other activities made prior to 15 July 2020, it also stated that ‘contracts and other agreements signed prior to 15 July 2020’ are not grandfathered. The fact of amending the guidance strongly suggests that the imposition of sanctions under CAATSA cannot be ruled out, at least as far as investments and agreements made after 15 July 2020 are concerned. On the same date as the guidance was amended, the US Secretary of State, Pompeo, stated that this was ‘a clear warning’ to companies involved in NS2 to ‘get out nor, or risk the consequences’.[i]

The US has also adopted the Protecting European Energy Security Act (PEESA) as part of its annual National Defence Authorisation Act (NDAA), which became law on 20 December 2019. PEESA stipulates sanctions on persons which have knowingly ‘sold, leased, or provided’ vessels that are ‘engaged in pipe-laying at depths of 100 feet or more below sea level’ for the construction of NS2 pipelines, or ‘facilitated deceptive or structured transactions to provide’ such vessels. On 18 December 2019, two days before NDAA was signed into law, two US senators – Cruz and Johnson – sent a letter to Allseas, stating that PEESA was passed ‘specifically to immediately halt’ Allseas work on NS2 and warning that its continuation would ‘expose’ Allseas to ‘potentially crushing and fatal legal and economic sanctions’.[ii] On 21 December, Allseas suspended its pipelaying activities, thus jeopardising the NS2 expected completion date (see previous section).

At the time of writing, the US is considering adoption of the Protecting European Energy Security Clarification Act (PEESCA). It builds on PEESA and also envisages sanctions for the provision of ‘underwriting services or insurance or reinsurance’ and ‘services or facilities for technology upgrades or installation of welding equipment for, or retrofitting or tethering’ of the vessels; and – as per the Senate, but not the Congress, draft – ‘services for the testing, inspection, or certification necessary for, or associated with the operation’ of NS2. PEESCA’s all-encompassing nature suggests it aims at making completion of NS2 as difficult and delayed as possible, potentially sanctioning any (European or non-European) company involved. PEESCA could be adopted in late 2020 as part of annual NDAA.

On their part, Germany and the EU have been growing increasingly uneasy about US sanctions initiatives. On 2 July 2020, the German chancellor, Merkel, stated that the extraterritorial sanctions are ‘not in line with our understanding of the law’.[iii] On 17 July 2020, the EU High Representative for foreign policy, Borrell, echoed the same sentiment saying that the EU ‘considers the extraterritorial applications of sanctions to be contrary to international law’ and ‘opposes the use of sanctions by third countries on European companies carrying out legitimate business’.[iv] Nonetheless, on 5 August 2020, three US senators – Cruz, Johnson and Cotton – sent a letter to Faehrhafen Sassnitz, an operator of the German port of Mukran (the NS2’s main logistical hub), warning it about ‘crushing legal and economic sanctions’ should it ‘continue providing goods, services, and support’ for NS2 and stating that its ‘provisioning of the Fortuna or Akademik Cherskiy will certainly have become sanctionable the instant that either vessel dips a pipe into the water’.[v] The letter cites both existing (CAATSA and PEESA) and potential (PEESCA) legislation as the basis for imposing sanctions.

However, an overwhelming majority of EU member states oppose extraterritorial sanctions on NS2, as demonstrated by the fact that on 12 August, one week after the senators’ letter was sent, the EU delegation in the US organised a call with the US State Department, during which 24 EU member states have expressed their opposition to sanctions.[vi] It is possible that should the US decide to impose sanctions in respect of NS2 either under existing or new legislation, the EU might add such legislation to the Blocking Statute Regulation,[vii] which prohibits the EU companies to comply with extraterritorial sanctions and stipulates a compensation mechanism in respect of the damages caused by non-compliance.

Conclusions

Although NS2 has faced serious headwinds and has been delayed beyond its original schedule – by both the late grant of the Danish permit and the adoption of the US sanctions legislation – it is likely that both of its lines will be built and become operational in the early 2020s. German government support for the project was conditional on the conclusion of post 2019 Russia-Ukraine transit agreement, which guaranteed a continued transit revenue for Ukraine at least until the end of 2024, even though some gas flows were to be redirected towards NS2 and away from Ukraine. Although a number of issues, not related to the project itself, have threatened to undermine the German government support for NS2 – most recently the poisoning of Navalny (the most high-profile Russian opposition figure) in August 2020 – this author expects the project to be completed. While there are uncertainties about exactly when NS2 will become operational, conclusion of post 2019 Russia-Ukraine transit agreement has made it less urgent for Gazprom to have access to its capacity. Once completed, NS2 could face regulatory obstacles posed by the amended Gas Directive, but these are unlikely to result in significant caps on Gazprom’s ability to utilise its capacity. NS2 will provide Russia with a significant surplus of pipeline export capacity towards Europe and hence flexibility ensuring that Gazprom’s exports to Europe will not be artificially constrained in the 2020s and beyond.

[i] Secretary Michael R. Pompeo at a press availability, 15 July 2020.

[ii] Cruz and Johnson letter to Allseas CEO, 18 December 2019.

[iii] ‘Germany’s Merkel says ‘right’ to complete Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline’, Platts, 2 July 2020.

[iv] Statement by the HR/VP Josep Borrell on US sanctions, 17 July 2020.

[v] Cruz, Cotton and Johnson letter to Faehrhafen Sassnitz, 5 August 2020.

[vi] Poland and Estonia have since stated they did not join this initiative, Politico, 13 August 2002.

[vii] Regulation 2271/96, 22 November 1996; Regulation 2018/1100, 6 June 2018.

Email: Katja.Yafimava@oxfordenergy.org

Expert article 2780