Bloom’s Taxonomy

Learning to learn and Bloom’s taxonomy

The following will explore in detail how Bloom’s taxonomy and ideas from research on self regulated learning, especially metacognition can help guide the creation of a rich environment for learners. Some of the core goals of education have traditionally been focused on acquiring, understanding and applying knowledge and skills. However the idea that one of the most pressing goals is actually to help learners develop their own self efficacy has become increasingly important.

Self-efficacy through Learning to learn

Self-efficacy is probably best explained using the concept of “learning to learn” defined by the European Union (2006):

“Learning to Learn is the ability to pursue and persist in learning, to organize one’s own learning, including through effective management of time and information, both individually and in groups. This competence includes awareness of one’s learning process and needs, identifying available opportunities, and the ability to overcome obstacles in order to learn successfully.”

These characteristics depend not just on knowledge, skills and attitudes but also self-knowledge and social capabilities. These combine to give the learner power over how to regulate their own learning.

Bloom’s taxonomy as a means to organize learning

The second revision of the taxonomy uses these action verbs:

Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyse, Evaluate and Create

These verbs are intended to describe the key cognitive processes across ages and subjects. This is seen as a helpful way for educators to plan and assess educational objectives. The taxonomy then provides a clear language for educators and learners to communicate these goals and make judgements about where and how they had success or need to improve their learning.

Metacognition as self-awareness of learning processes and needs

Metacognition involves learners developing knowledge of the strategies they use and how they apply these in their learning tasks. Also self-knowledge of how appropriately and successfully they apply these strategies. This is where explicit naming and teaching of strategies and classroom discussion of when and how to apply them will help make these processes become “visible” to the learners.

References

Learn To Learn, URL http://www.learntolearn.eu/ (accessed 8.2.20).

Learning to learn assessment [WWW Document], 2018. . University of Helsinki. URL https://www.helsinki.fi/en/networks/centre-for-educational-assessment/learning-to-learn-assessment (accessed 8.2.20).

Council, E., 2006. Recommendation of the European Parliament and the Council of 18 December 2006 on key competencies for lifelong learning. Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union 30, 2006.

ACTS / Alex Black – Bloom

Bloom's taxonomy in ACTS

Introduction

The following two articles will explore in detail how Bloom’s taxonomy and ideas from research on self regulated learning, especially metacognition can help guide the creation of a rich environment for learners. Some of the core goals of education have traditionally been focussed on acquiring, understanding and applying knowledge and skills. However the idea that one of the most pressing goals is actually to help learners develop their own self efficacy has become increasingly important.

Self efficacy through Learning to Learn

Self efficacy is probably best explained using the concept of “learning to learn” defined by the European Union (2006)

“Learning to Learn is the ability to pursue and persist in learning, to organize one’s own learning, including through effective management of time and information, both individually and in groups. This competence includes awareness of one’s learning process and needs, identifying available opportunities, and the ability to overcome obstacles in order to learn successfully.”

These characteristics depend not just on knowledge, skills and attitudes but also self knowledge and social capabilities. These combine to give the learner power over how to regulate their own learning.

Bloom’s taxonomy as a means to organize learning

The second revision of the taxonomy uses these action verbs:

Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyse, Evaluate and Create

These verbs are intended to describe the key cognitive processes across ages and subjects. This is seen as a helpful way for educators to plan and assess educational objectives. The taxonomy then provides a clear language for educators and learners to communicate these goals and make judgements about where and how they had success or need to improve their learning.

Metacognition as self awareness of learning processes and needs

Metacognition involves learners developing knowledge of the strategies they use and how they apply these in their learning tasks. Also self knowledge of how appropriately and successfully they apply these strategies. This is where explicit naming and teaching of strategies and classroom discussion of when and how to apply them will help make these processes become “visible” to the learners.

References

Learn To Learn, URL http://www.learntolearn.eu/ (accessed 8.2.20).

Learning to learn assessment [WWW Document], 2018. . University of Helsinki. URL https://www.helsinki.fi/en/networks/centre-for-educational-assessment/learning-to-learn-assessment (accessed 8.2.20).

Council, E., 2006. Recommendation of the European Parliament and the Council of 18 December 2006 on key competencies for lifelong learning. Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union 30, 2006.

Article 1

Bloom’s Taxonomy and the Goals of Assessment Companion for Thinking Skills (ACTS) in Rauma

The Teacher training School in Rauma had set itself 3 key goals in their ACTS project.

- How to develop Student and Teacher self efficacy

- How to make thinking visible

- How to use Bloom’s Taxonomy as a visual and language tool to assess and help develop thinking

This article will explore some of the limitations of the original Bloom’s Taxonomy (Bloom, et al 1956) already long discussed by Bloom and his associates (Furst, 1981), (Anderson, 1999) and (Krathwohl, 2002) and how their revision led to the creation of a fruitful framework for the ambitious goals Rauma had set themselves.

The reasoning behind the revised taxonomy and how this has provided the

“common language about learning goals to facilitate communication across persons, subject matter, and grade levels;” (Krathwohl, 2002 p. 212) will be explored.

Examples will be given as to how the arguments against the hierarchical nature of the taxonomy are helpful in planning learning episodes. These will allow for analytical, creative and evaluative activities and discussions. These activities can be embedded in classroom learning from the outset. The design of these episodes will be shown to help make student thinking visible, both to the teacher and students themselves. These passages of learning will be evaluated in terms of how useful they are in the assessment of thinking so that it can help students become aware of their own thinking progress.

Finally, the increase of the dimensions of the revised taxonomy to include the metacognitive

knowledge dimension is welcomed as a clear path to making thinking visible and helping the growth of student self efficacy. (Krathwohl, 2002 p. 213) gives an excellent introduction to the importance of metacognitive knowledge.

“One of the most important aspects of teaching for metacognitive knowledge is the explicit labeling of it for students. For example, during a lesson, the teacher can note occasions when metacognitive knowledge comes up, such as in a reading group discussion of the different strategies students use to read a section of a story. This explicit labeling and discussion helps students connect the strategies (and their names/labels) to other knowledge they may already have about strategies and reading.”

The second article in this series will explore the practical ways metacognition can be furthered in learning episodes for thinking.

The Original Taxonomy

Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Bloom, et al 1956) was a huge endeavour to make a descriptive, comprehensive and neutral framework to plan and assess educational programmes. It was intended to be non prescriptive as to pedagogy and other educational values. (Krathwohl, 2002 p. 212) maps out the comprehensive and descriptive nature of the taxonomy.

“The original Taxonomy provided carefully developed definitions for each of the six major categories in the cognitive domain. The categories were Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation. With the exception of Application, each of these was broken into subcategories.”

Discussions of limitations

The knowledge dimension

The original partition of knowledge into factual, conceptual and procedural was intended to gain clarity about the very nature of knowledge and behaviours that can be used to assess if knowledge has been acquired. However these raised fundamental issues that have not been fully resolved to this day. How do we know someone has learnt or knows something? What inferences can we make when they behave in response to a question or stimulus? When a student answers in a certain way what does this mean?

These knowledge issues have been constant themes in the ACTS project and underpin the idea of finding ways Teachers can make something as abstract as thinking become more visible and available to assessment.

(Furst, 1981) discusses the philosophical issues and their implications of the knowledge issue and highlights how Bloom and his co-workers were aware of these issues from the outset.

“First, knowledge could involve the ability to recall specifics and universals,

methods and procedures, or patterns and structures “(Bloom et al., 1956, p. 201).

Using this definition, knowledge is the ability to recall. A second definition of knowledge appears in an analogy made by the authors of the original Handbook. “If one thinks of the mind as a file, the problem in a knowledge test situation is that of finding in the problem or task the appropriate signals, cues, and clues which will most effectively bring out whatever knowledge is filed or stored’ (Bloom et al., 1956)

Krathwohl (2002 p.213)

The revised taxonomy took these criticisms into account and tried to resolve the conflict by expressing the knowledge definitions in terms of nouns and the cognitive processes in terms of verbs, “This anomaly was eliminated in the revised Taxonomy by allowing these two aspects, the noun and verb, to form separate dimensions, the noun providing the basis for the Knowledge dimension and the verb forming the basis for the Cognitive Process dimension.”

The hierarchy of cognitive processes

(Furst, 1981) examined the concept of the taxonomy being a linear hierarchy of increasingly complex cognitive behaviours and rejects this on philosophical and educational grounds

“The notion of a cumulative hierarchy, ordered on a single dimension of simple-to-

complex behavior has provoked strong philosophical criticism of the taxonomy. But

no matter what the hierarchical scheme, the linear assumption is suspect on general

philosophical grounds.” (Furst, 1981 p. 446). However as educators we must recognise that some cognitive processes are more demanding than others and we often want to help students proceed through more and more challenging objectives as they mature during their schooling.

“Not all who opt for a classification insist on one organized as a hierarchy; but for some, the notion of hierarchy has much appeal. And rightly so, for hierarchy is fundamental in the make-up of skills, abilities, and conceptual organizations of subject matter. ….. Hierarchical schemes may consist of categories of mental operations but ultimately the referents of these must center on cognitive tasks and the products there from.”

(Furst, 1981 p. 450)

So to avoid the problems related with the linear interpretation of the taxonomy but still structure a guided and challenging curriculum we need a new interpretation. This could be a plan to choose classroom learning activities that are aligned with our educational objectives of making thinking more visible. These will also allow access for students of different prior knowledge, experience and readiness to contribute to their own learning as they increase their awareness of this. The language and framework of Bloom et al is a powerfully useful guide in providing a means of making learners increase their efficacy in controlling their own experiences.

The revised taxonomy summarised

- The knowledge dimensions expanded

Factual Knowledge – Conceptual Knowledge – Procedural Knowledge – Metacognitive Knowledge

- The nouns changed to verbs and the order changed

Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation.

Became

Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyse, Evaluate and Create

Opportunities and strategies to make thinking visible

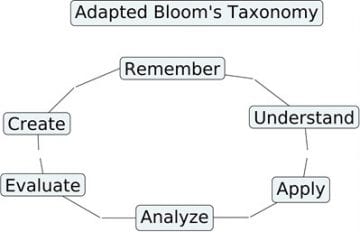

Let us look at a simple mathematical example using an interpretation of a non linear Bloom’s taxonomy shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

In a lesson with second year primary students they are shown a number grid as shown below in Table 1

Table 1

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

The teacher introduces the idea of analysing these numbers. Analysing literally is the verb to break down or split something into parts. This analysis can be made very concretely visible by sorting, shading etc. After some discussion many students can spilt these numbers into the class of odd and even numbers. Several different types of analysis can be done with a variety of cognitive demands and complexity.

Then students are challenged in creating some rules that they notice about odd and even numbers. In this example students can often create such formulations :

If you add two odds you always get an even.

If you add two evens you always get an even .

If you add an even and an odd you always get an odd.

Students may have created these rules by remembering and formulating their recall, or they may have used some simple intuition based on randomly adding and generalising from the results. Create was placed at the summit of many representations of the revised taxonomy, but these examples show that creation has a range of complexities from some form of modified recall, a simple intuition and up to a new generalised insight.

Evaluating these rules can also be made at a very simple level of just using a small number of confirming examples. We as teachers can scaffold the evaluation and associated metacognition with scaffolding questions. For example, are there any more examples? What happens with numbers above 50, 100? Does the rule still hold true? Are there rules about subtraction and multiplication?

A more advanced level of evaluation with older students would be to use algebraic forms to prove these rules. e.g The general odd number is 2n+1 and the general even is 2n. Use these to evaluate the rules. Generalising this to all of the rules you can make.

What is important about the use of these three Bloom verbs is that they allow a scaffolding structure to show students how to express and formulate their thoughts about the task and also to talk about their own thoughts. This is a very important step in making thinking visible and leads to increased self efficacy.

Conclusion

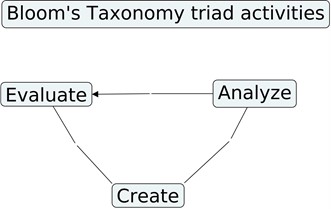

Figure 2

This article actually argues that cognitive processes such as analysing, creating and evaluating should be explored in learning that demands the use of all three of them. The order and complexity that they are used should fit the needs and stage that the children are at.

There are many examples of this analysis, create rule(s) and then evaluate the rule(s).

An example from geography list some at Country/County/province Capitals and information about their size. What rules /patterns can be seen? How good are these patterns or rules?

Similar work can be done in analysing literature texts/diagrams/charts/pieces of art etc. and noticing patterns and creating rules.

Again it must be stressed that all of these activities allow for a variety of ways of making thinking visible with a few well understood cognitive verbs that have wide applicability.

The usefulness of Bloom’s taxonomy is extensively discussed by (Furst 1981 p 450) and he comes to a positive but balanced conclusion similar to ours.

“ Even two of the severest critics, Hirst and Ormell, were complimentary of the taxonomy for opening the issue of classification, bringing out the great diversity of objectives, and helping educators avoid concentrating on the usual limited range…. The enormous influence

exercised by their imperfect tool proves that it answered a deep and urgently felt

need”

This article argues that such tools that furnish a commonly shared language of thinking is a great social mediator in the sense Vygotsky suggested about human learning and development.

“human learning presupposes a specific social nature as a process by which children grow into the intellectual life of those around them” (Vygotsky, 1978, p.88)

This is why we should use the framework to identify thinking, use it to give feedback to students, teach them how to use the framework to assess their own thinking and share their development publicly.

References

Anderson, L.W. (1999). Rethinking Bloom’s taxonomy: Implications for testing and assessment. (ERIC Document Reproduction Ser-vice No. ED435630).

Bloom, B.S. (Ed.), Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., & Krathwohl, D.R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay.

Furst, E.J., (1981). Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives for the Cognitive Domain: Philosophical and Educational Issues. Review of Educational Research 51, 441–453. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543051004441

Krathwohl, D.R., (2002). A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview. Theory Into Practice 41, 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Article 2

Metacognition as a key element of the Assessment Companion for Thinking Skills (ACTS) project in Rauma

This article will try to clarify

- What research has said about the efficacy and conceptualisation of metacognition.

- What are the key knowledge and process dimensions of metacognition.

- What processes learners need to employ and how these can be taught.

Why metacognition is very important

Muijs and Bokhove (2020 p. 4), who contributed to a very influential Educational Endowment Fund (EEF) report, discuss the literature evaluating the evidence of the impact of metacognition and self regulated learning.

“Metacognition and self-regulated learning (SRL) have been advocated by many, and have significant support being seen as a potentially effective and low cost way of impacting learning. Fundamentally, the underlying supposition is that metacognition and SRL are important to learning, and thus raise attainment, and various studies have established that SRL, and in particular metacognition, has a significant impact on students’ academic performance, on top of ability or prior achievement”

A very interesting study that challenges a long held assumption that metacognition was not really effective for the early cognitive development of children. This was clearly challenged by Muijs and Bokhove (2020 p. 4)

“Studies suggest that early forms of metacognition are predictive of later attainment, one study of Finnish children, for example, finding that metacognition at age 3 was directly predictive of mathematics performance at age 6, and indirectly predictive of rate of growth maths performance between ages 3 and 6 (largely through its effect on counting ability) quoting (Aunola et al, 2004).”

This article will assume the argument that we should try to develop metacognition as an important aspect of self regulated learning wherever possible across age and subject areas.

We will try to get clarity about the knowledge, processes and the different aspects of metacognition. This will allow us to inform our ways of teaching, scaffolding and assessing the growth of our learners.

Dimensions of metacognitive knowledge

The addition of the category of metacognitive knowledge into the revised Bloom’s taxonomy is discussed at length by Krathwohl (2002) and Pintrich (2002). This addition was also guided by the sub dimension described by Flavell (1979 p.219), namely

“Metacognitive knowledge includes knowledge of general strategies that might be used for different tasks, knowledge of the conditions under which these strategies might be used, knowledge of the extent to which the strategies are effective, and knowledge of self.”

Knowledge of Strategies, Task and Self

Taking these as key components in guiding the development of self efficacy this article argues that these sub dimensions will allow clear guidance for whole class, small group and individual feedback and discussion. The specific focus on how a learner approaches and succeeds on educational tasks. These will allow for many opportunities for self reflection using these 3 specific categories to spotlight in their thinking.

Questions that teachers can use and then encourage learners to internalise could be scaffolded at different levels within Bloom’s taxonomy.

How would we describe the task? Can we recall similar tasks and strategies we have learnt or used in the past? What did I find easy/difficult? What did I find this task difficult? If I had used a different strategy would that have helped?

These dimensions, and their ability to generate questions, will also be very useful to teachers, students and curriculum designers who want to formatively assess and help develop these aspects of metacognitive knowledge.

Cognitive processes as features of metacognition

The revision of Bloom’s taxonomy made a clear distinction between

“the noun and verb, to form separate dimensions, the noun providing the basis for the Knowl-

edge dimension and the verb forming the basis for the Cognitive Process dimension.”

Krathwohl (2002 p.213).

This is taken as a fruitful distinction to frame how teaching environments can increase the use of verbs, actions and discourse to help the development of rich metacognitive environments.

Muijs and Bokhove (2020) discuss the literature evaluating the evidence of the impact of metacognition and self regulated learning. They then conclude from the work of Schraw, Crippen, and Hartley (2006), the role of metacognition is the most important,

“because it enables individuals to monitor their current knowledge and skills levels, plan and allocate limited learning resources with optimal efficiency, and evaluate their current learning state” (p. 116). Muijs and Bokhove (2020 p.6) that the key processes in metacognition are:

“Regulation of cognition includes at least three main components: planning, monitoring and

evaluation:

(1) Planning relates to goal setting, activating relevant prior knowledge, selecting appropriate

strategies, and the allocation of resources.

(2) Monitoring includes the self-testing activities that are necessary to control learning.

(3) Evaluation refers to appraising the outcomes and the (regulatory) processes of one’s

learning.

Teaching metacognition

Muijs and Bokhove (2020 p.27) in considering what the evidence has to say about how best to teach metacognition suggest two main approaches:

“The evidence suggests that effective teaching of SRL and metacognition has two main elements:

The direct approach, through explicit instruction and implicit modelling by the teacher

The indirect approach, through creating a conducive learning environment, with guided

practise, including dialogue and (scaffolded) inquiry.”

They also argue that although metacognition is rated as cheap as an educational intervention it needs to be supported by ongoing Teacher Professional development to ensure the modelling, language and fruitful environment for metacognition are maintained.

References

Aunola, K., Leskinen, E., Lerkkanen, M.k.& Nurmi, J.E. (2004). Developmental dynamics of math performance from preschool to grade 2. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(4), 699-713.

Flavell, J. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34, 906-911.

Krathwohl, D.R., (2002). A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview. Theory Into Practice 41, 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

Muijs, D. and Bokhove, C. (2020). Metacognition and Self Regulation: Evidence Review. London: Education Endowment Foundation.

Pintrich, P (2002) The Role of Metacognitive Knowledge in Learning, Teaching, and Assessing, Theory Into Practice, Volume 41, Number 4, 219-225, https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_3