The business opportunity of reducing emissions in shipping

Magnus Gustafsson,

PhD, Research Leader,

Åbo Akademi Laboratory of Industrial Management,

Finland

Partner,

PBI Research Institute,

Finland

Henry Schwartz,

Doctoral Student,

Åbo Akademi Laboratory of Industrial Management,

Finland

Shipping is a key industry in international trade and emits one billion tons carbon dioxide per year – two percent of global emissions. For the shipping industry reducing its emissions and doing its fair share in helping to avoid global warming constitutes a significant challenge. Ships have long lifespans, often over 30 years and some analyses show that for the shipping industry to achieve net zero by 2050 all newbuilt ships would have to be zero-emission starting today – no small feat.

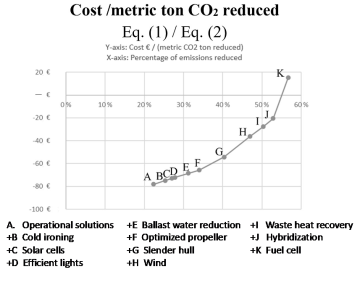

However, the picture is not completely dark. Analyses show there are numerous technologies that could help reduce emissions from operational measures optimizing the utilization of existing capacity, new technologies that reduce energy consumption and renewable fuels (figure 1). In fact, analyses show many of these could provide quite profitable investments. Optimizing logistic flows and especially cargo flows would not only reduce the fuel consumption per ton of cargo but also increase the utilization rate of ships while energy-saving technologies not only reduce emissions but also reduce costs by reducing fuel consumption.

Figure 1. Cost of reducing emissions €/metric ton CO2 reduced. Adapted from Schwartz, Gustafsson & Spohr (2020)

Why is it then that the needed investments into reducing emissions are proceeding much too slowly? Take the example of ships rushing to wait at the anchorage point in front of the port leading – in some cases tens of ships waiting for weeks. In a time when any normal person can check their smartphone and inform their friends, they will be five minutes late and ask them to order in their place, ships still steam full ahead to get a place in the queue to the port. Analyses show eliminating this rush-to-wait would reduce global ship fuel consumption by 10% thereby reducing both fuel costs and emissions. On a global scale the ICT investment needed would amount to perhaps 100 million USD – a paltry sum in an industry that spends around 90 billion USD on fuel annually.

Rush to wait has been debated for a long time in the shipping industry. Many software companies have also proposed brilliant technologies with which the problem could be solved. New contract models have also been developed since it turned out that one key reason for ships rushing to wait was that contract models were still from the time when you would scan the horizon through binoculars to spot ships approaching ports. Yet still the problem remains and the reason for the persistence is to be found in the last point – old-fashioned business models.

The shipping industry is an old industry with well-established routines and traditions. Some of these are codified into regulations and standard while others are part of the established way of working and culture. These routines, regulations, standards, and traditions reduce uncertainty and provide stability in a challenging business. However, over time they can become outdated and hinder the introduction of new technologies that could improve the performance and sustainability of the industry – leading to the persistence of phenomena like rush-to-wait, which can only be described as lose-lose. Rush-to-wait is far from the only lock-in plaguing the shipping industry.

Lock-ins like rush to wait are wicked problems. They are embedded throughout the value chains. They emerge and are validated every time a freight contract, an investment or similar decision is made the traditional way and are perpetuated by the silofication and fragmentation that characterizes the shipping industry and its stakeholders. This means investments often have difficulty achieving profitability because they are constrained by the established business models of other stakeholders in the value chain.

However, therein also lies the business opportunity. By identifying the lock-ins and incumbent business models constraining the investment solutions can be devised that enable profitability and scalability. The next step is to outline how the technology could change the roles of different stakeholders, the division of roles and responsibilities and information flows and based on that identify how they should be engaged in the new value-creation process. This can include new value propositions, partners, risk-sharing mechanisms and incentives.

The shipping industry is a value-creating ecosystem that provides valuable services to society. It is an old industry that has gone through many changes and metamorphoses. There is still a lot of room for improvement and there are many companies bringing promising technologies to the market that can increase the sustainability of the industry. By developing and changing the business models of the industry, technology can be introduced that not only reduces emissions and increases sustainability but does so profitably. After all, for something to be sustainable it is not enough that it is environmentally and socially sustainable, it needs to be economically sustainable too.

Expert article 3118

> Back to Baltic Rim Economies 5/2021

To receive the Baltic Rim Economies review free of charge, you may register to the mailing list.

The review is published 4-6 times a year.