From one neighbourhood to another – Implementing a citizen survey in the Urban Biodiversity Parks -project

Ulrika Stevens, Department of Geography and Geology, University of Turku

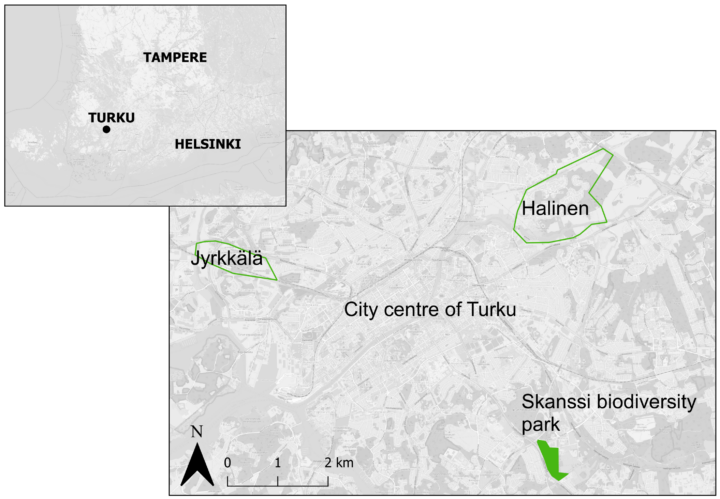

The Skanssi biodiversity park in Turku is being developed into a pilot site for promoting urban biodiversity. The concept of a biodiversity park is to actively enhance biodiversity and provide a recreational area to urban residents. The residents have the possibility to learn about biodiversity and join in nature management activities. In addition to the establishment of the Skanssi park, two pilot areas have been selected for partial replication of the concept through biodiversity enhancing measures. In the autumn of 2024, our team conducted a map-based citizen survey among the neighbourhood residents to gain insights of their usage of green spaces and preferences for biodiversity enhancing measures.

Figure 1. Locations of Jyrkkälä, Halinen and Skanssi biodiversity park in Turku, Finland. Source: OpenStreetMap.

Both neighborhoods are culturally diverse, with inhabitants from multilingual backgrounds. Halinen has 3500 inhabitants living in mixed housing areas, and Jyrkkälä 1300 inhabitants living in 17 apartment buildings owned by the same rental housing company. The neighborhoods share similar socio-economic characteristics including large number of families with children, a high share of low-income earners and unemployed residents. To learn more about the natural and built environment of the neighbourhoods, see here the storymaps created of Halinen and Jyrkkälä.

Figure 2. A) Halinen, Turku © Selina Raunio and B) Jyrkkälä, Turku © Vera Laaksonen.

Participatory mapping is a widely used method to collect place-based knowledge from citizens. Our survey included the following themes: use of local green and outdoor spaces, values attached to nature, preferred measures to enhance urban biodiversity, and perceptions of communality.

To increase accessibility, the survey was available in 8 different languages (Finnish, Swedish, English, Russian, Arabic, Ukrainian, Sorani and Somali). Students of social work from the Applied University of Turku assisted in the process as part of their course work by contacting and helping residents to fill out the survey. It was also possible to access and answer the online survey independently through a QR-code, which we circulated in the neighbourhoods through flyers, posters, and social media.

In total, 152 people responded to the survey (Halinen, 94 people; Jyrkkälä, 58 people). As is evident with our survey, a common challenge of participatory mapping surveys is that participants drop out towards the end without finishing it or specifically quit the survey while answering map-based questions. This task can be perceived as challenging to undertake.

Through spending time in the neighbourhoods and participating in local activities, we aimed to create a sense of trust with residents and collect face-to-face survey answers. This process was different in both neighbourhoods, as the communal activities that take place there differ.

We were warmly welcomed to collect our survey data at the weekly sauna-and-coffee gathering of men who live alone and were served home-made cinnamon buns during the weekly elderly meeting. Often at these gatherings, we would meet many of the same people. It became evident that it is more difficult to reach those that do not participate in these social gatherings, such as families. Especially gatherings where most people speak Finnish and come from a traditionally Finnish background were prominent, while gatherings of other residents were more difficult for us to find. However, this was not the case for the youth centre, where many of the young people are second-generation immigrants. Most of the responses gained in Jyrkkälä were through these encounters with residents, with a few locals answering independently online. While most respondents speak Finnish as their mother tongue, some respondents mentioned for example Estonian, Albanian or Turkish as their mother tongue, while also speaking Finnish.

Figure 3. A) Participatory mapping session in Jyrkkälä, B) co-creating a temporary environmental art at the nature party in Halinen, C) studying soil organisms at the nature party in Halinen. © Ulrika Stevens.

In Halinen, as the area is larger in size, more emphasis was given to walking around the neighbourhood and handing out flyers with the QR code. Unlike in Jyrkkälä, most responses gained in Halinen were through independent responding online, while we had a low reach of residents via physical presence in the neighbourhood. This outcome was expected because there are less communal spaces and activities in Halinen. Housing for higher education students and doctoral researchers, among them also internationals, is located in the neighbourhood, which enabled us to gain insights into the perceptions of residents from multicultural backgrounds, with respondents marking the following languages as their mother tongue for example: Farsi, German or Urdu.

Additionally, we hosted a nature party in Halinen, where people could come to learn about the project and participate in the survey. To create more connection to the neighbourhood, the event was hosted at the local elementary school, with catering provided by a local cultural and environmental association. In the gloomy autumn weather, the event attracted children, their families, and elderly people from various backgrounds. From studying soil organisms with microscopes to planting your own herbs, there was something for people of different ages at the nature party.

The results of the survey will next be analysed and then presented in face-to-face workshops with residents. In the workshops, we will also test additional digital participatory technologies for residents to share their perspectives for green planning. The implementation of the jointly planned solutions will take place in 2025 and 2026 and are meant to live on past the duration of the project through active residents.

Figure 4. Ulrika Stevens and Nora Fagerholm presenting the Urban Biodiversity Parks -project at the Finnish Geography Days 2024 in Turku, Finland.

The Urban Biodiversity Parks -project in a nutshell

As the first urban biodiversity park in Europe, the biodiversity park of Skanssi will be a pilot and flagship area for combating biodiversity loss and increasing urban biodiversity in Finland. Lean more about the project here. The project has received funding from the European Union’s European Urban Initiative – Innovative Actions (EUI-IA) funding programme. The project will run from 2024 to 2027.