Research nightmares? Two key lessons from my first PhD fieldwork in Malawi

Frank B. Chimaimba, Department of Geography and Geology, University of Turku

Introduction

I’m not sure if this is common, but I’ve always had a quiet fear of research fieldwork. Sometimes, just thinking about it was enough to steal my sleep and peace of mind — like a nightmare. Perhaps the fear comes from lack of preparation, limited resources, or inexperience — that feeling of stepping into the unknown. But in my case, none of these reasons applied.

At the start of 2025, I was in Turku, Finland, preparing for my first PhD data collection fieldwork in Malawi. My plan was to conduct a survey, physically meeting residents of Lilongwe from both planned and unplanned areas, to understand how they value urban nature — whether positively or negatively — through their daily activities. On paper, everything was in place, and I had done all the necessary preparations. Yet I was still afraid— and I kept asking myself: “What exactly am I afraid of?”

Reflecting back, I realize much of that fear stemmed from the uncertain nature of fieldwork, something rarely discussed, because it feels different for everyone. You can plan endlessly, but the field always has its own rhythm, full of surprises and challenges you cannot anticipate.

In this blog, I reflect on that uncertainty through my own experience. I share two key lessons that helped me navigate challenges and turn my “nightmares” into meaningful learning. If you’re planning your first data collection fieldwork, especially in a distant or unfamiliar setting, this post is for you.

Before Fieldwork: Lesson 1 – Start the Ethics Process Early – It shapes your research thinking

I share this lesson first because it turned out to be one of the most important—and unexpectedly time-consuming—part of my fieldwork preparation. The key question every researcher should ask early on is: “Does my research require ethical clearance?”

The answer, almost always, is “yes”, especially for research like mine that involves people. Ethical approval is not only a formal requirement at universities but also something journal editors look for when you want to publish your findings. What I didn’t realize at first, however, was just how much this process would shape my research thinking- forcing me to reflect on my participants, my methods, and my responsibilities as a researcher before even entering the field.

Early in my PhD, my supervisors told me to apply for university research ethics clearance. I had no idea what that involved. Thankfully, their guidance, the university intranet, and a mandatory university course on research ethics helped me navigate the process.

Even with that support, I soon discovered that my case was a bit more complex. Since my research was based in Malawi, I also needed ethical clearance from the Malawi National Commission for Science and Technology. Suddenly, I had two separate ethical processes to navigate—one in Finland and another in Malawi. It felt overwhelming. Only then could I truly relate to the stories I had heard from other PhD students, who described the process as stressful and slow — almost like a nightmare.

The challenge wasn’t only the paperwork but also the patience required for the back-and-forth communication. In my case, it took me about three weeks just to prepare all the required documents—around eleven in total—each demanding careful thought and precision. I had to draft consent forms, recruitment letters, data protection statements, and descriptions of potential risks and benefits.

It was intense. I remember reviewing my documents late at night, double-checking every paragraph to ensure clarity and compliance. It felt tedious, even stressful, but starting early saved me from last-minute panic.

Looking back, I realized that the ethics process was more than an administrative hurdle; it was a mirror for my research design. It forced me to think deeply about the people I would engage with, how to protect their privacy, and what it truly means to conduct responsible research. In a way, the process helped me visualize my entire fieldwork journey before I even set foot in Malawi.

So, my key takeaway is simple: start early. Ethical review is not just a step to tick off—it’s the foundation that prepares you mentally, practically, and ethically for the field ahead.

During Fieldwork: Lesson 2 – Flexibility and perseverance are your strongest skills

No matter how carefully you plan, the field has its own surprises. Meetings get cancelled, transport fails, or participants aren’t available. Early on, these felt like crises — but they became lessons in adaptability.

One day during my fieldwork, my team and I arrived in Area 12, one of Lilongwe’s most affluent neighborhoods, with tall fences and guarded gates. After several days working in informal settlements, this new area felt intimidating and unfamiliar. I remember standing at the first gate, feeling a wave of anxiety — “what if no one agrees to talk to us?”

Knocking on multiple gates yielded the same result: silence or polite refusals. By noon, I had not spoken to a single respondent. My team reported the same struggle. It was discouraging — my fieldwork nightmare was unfolding in real time. Frustration set in, but I reminded myself: this is what fieldwork is really like — messy, and unpredictable.

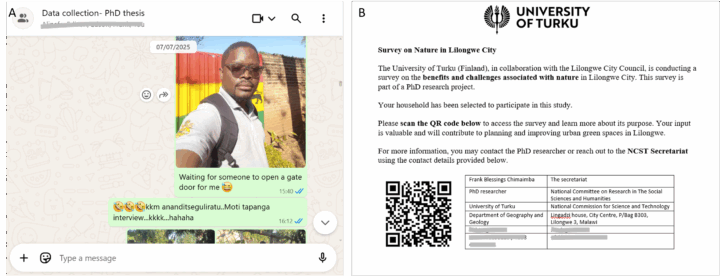

Sitting under a tree in the neighborhood to reflect: “What can we do differently?”. We realized we needed a new approach. We quickly designed a small information flier with a short introduction to the study, my contact details, and a QR code linking to the survey. The idea was to hand these fliers to the guards, who could pass them on to their employers.

Later that afternoon, we started using the flier, and the approach worked perfectly. Once receiving the fliers, the household owners would call us in to chat with them. Participation increased dramatically. What began as one of the toughest mornings of fieldwork became one of the most productive days.

This experience taught me that flexibility isn’t a backup plan — it’s essential. Being adaptable doesn’t mean losing focus; it means working with the field. Plans are only maps; the real journey begins when you step off the path.

In Finland, there’s a word that perfectly captures the mindset this situation required: “Sisu”. It describes the determination to keep going, to persevere through obstacles, and not give up even when success seems uncertain. Embracing sisu allowed me to stay calm, improvise, and turn a “nightmare” into an opportunity for learning and growth.

So, my key takeaway here is: Flexibility and perseverance are essential in adapting, staying calm, and turning setbacks into opportunities.

Figure 1A: A WhatsApp discussion during the data collection as I was waiting for someone to open a gate after knocking in area 12. Figure 1B: A flier developed during data collection as a response to refusals.

Conclusion: Turning Research Nightmares into Lessons

When I look back at my first PhD fieldwork in Malawi, I realize that what felt like “nightmares” at the time, the uncertainty, unexpected obstacles, and moments of self-doubt, were actually opportunities in disguise. Fieldwork is rarely smooth. It tests patience, creativity, and humility. But it is in navigating these challenges that we grow, not just as researchers, but as people. Success isn’t measured only by the data we collect, but by the lessons we learn and how we transform through the process.

In the end, the “nightmares” of fieldwork are not something to fear, rather they are the very experiences that make research meaningful, shaping how we see the world, understand others, and learn about ourselves.