Ancient DNA sheds light on medieval language exchange in the Volga-Oka river region (9.1.2023)

There are more than a hundred ethnic minorities living on the territory of present-day Russia, speaking at least a hundred minority languages in total. The largest minority language groups in the Volga and Ural Mountains are the Uralic languages. The Uralic languages are believed to have been much more widespread in the late Iron Age than they are today. Local ancestry and historical sources have made it possible to reconstruct the historical speech areas of these languages and to draw conclusions about extinct language forms.

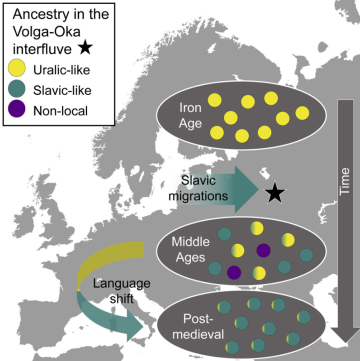

Slavic language and culture arrived in the Volga region in the second half of the first millennium. During this period, Slavic tribes spread from their original habitats (probably in the southern Baltic or eastern Europe) to all parts of the world, bringing with them their Slavic language and a varying amount of heritage. In the east and north, the Slavs contributed to the formation of the Rus Principality of Kiev from the late 800s onwards. According to historical sources, especially in the north-eastern parts of Kievan Rus, bilingual communities were formed at that time, speaking both Slavic and Uralic languages. Towards the Middle Ages, however, the Slavic languages gained importance with the advent of Christianisation and the Cyrillic alphabet. As a result of this development, the local Uralic language forms took a back seat and eventually disappeared altogether.

A person’s DNA cannot tell you what language they spoke in their lifetime or what ethnic group they belonged to. However, changes in the gene pool of a population can tell us about population movements and encounters between different groups of people, and together with historical and linguistic data, ancient DNA can shed light on the timing of events, for example. In a study published in Current Biology, we investigated how the historically known language shift from Uralic to Slavic languages is reflected in the genome of ancient people in the Volga-Oka River region. Of particular interest were the predecessors of the Slavs, who we assume spoke one of the extinct Uralic languages. What were they like genetically? And how much gene flow was involved in the language change?

In this study, we analysed genome-wide DNA data from 31 individuals from the Suzdal region of central Russia. The oldest specimens in the study come from a cemetery in Bolshoye Davydovskoye dating to the Roman Iron Age (ca. 300-400 AD). This cemetery, which represents the Iron Age culture of the Volga region, mainly buried women and children. Early Slavic settlement was represented by the Shekshovo cemetery and a slightly more eastern burial from Gorokhovets (c. 800-1200 AD). The late medieval and historic period was represented by Kibol, Krasnoe, Kideksha and Gorokhovets Sretensky (1400-1800 AD).

Compared to the modern Eurasian population, the Iron Age inhabitants of Bolshoye Davidovskoye were the most genetically similar to modern Russians from the Arkhangelsk region. The Russians of this region, as well as almost all Uralic speakers, have a lot of so-called Siberian heritage, which is absent in most other Europeans. Although only Russian is spoken in Arkhangelsk today, it is likely that Uralic languages were also spoken there in the past, and that the population has undergone language changes and genetic mixing with Slavicisation in the same way as in the Volga region. On the other hand, the genomes of the inhabitants of Bolshoy Davidovskoy showed a stronger link with the ancient hunter-gatherers of the region than the northern Russians or the present-day Uralic speakers of the Volga region, which is an indication of the distinctiveness of this Iron Age population.

The genomes of the younger individuals in the study reflect the known linguistic history of the area: early medieval burials contained individuals genetically similar to both modern East Slavs and Uralic speakers, but only limited mixing of the two groups. This supports the historical interpretation of the bilingual communities of the Kievan Rus. Interestingly, there is no difference in burial practices or grave goods between the two genetic groups, which may indicate that the community was culturally united. Individuals from the late medieval and historic periods could be modelled as a mixture of the two earlier genetic groups – with about 70% of the genome of the historic period population coming from the ‘Slavic’ part of the population and the rest from the ‘Uralic’ group.

Figure: A visual summary of the results of the study.

Peltola et al., “Genetic admixture and language shift in the medieval Volga-Oka interfluve” Current biology (2023)

It is important to remember that genes do not tell us anything about the language a person speaks or their ethnic identity. We can only make indirect inferences about the languages that may have been spoken in ancient communities based on genetic data and compare genetic findings with linguistic and historical data.

We also found individuals in our data set whose genomes suggest an origin outside of Northeastern Europe. Two young men from Shekshovo, dating from the 1200s, are genetically close to Central Asian pastoral people speaking Turkic languages, such as Kazakhs, Karakalpak and Siberian Tatars. Many of these peoples served as border guards in Kiev Rus in the 13th century. In addition, an individual found in Kideksha, dating from the 15th century, probably carried a small proportion of Middle Eastern or Caucasian ancestry. The genomes of these individuals provide concrete evidence of the mobility of ancient individuals and of the long-range contacts of the Kievan Rus.

Literature:

Peltola S, Majander K, Makarov N., Dobrovolskaya M., Nordqvist K, Salmela E. & Onkamo P. Genetic admixture and language shift in the medieval Volga-Oka interfluve. Current Biology 33(1), 174-182.e10, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.11.036, 2023.