Turkkilainen Turkulainen: Linguistic observations of a teacher of Turkish and learner of Finnish

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founding figure of the Turkish Republic, ordered the inclusion of the book “Finlandiya: Beyaz Zambaklar Ülkesinde” “Suomi: Valkoisten Liljojen Maassa” in the Turkish military school curricula during the late 1920s. He was inspired by the success story of the foundation of Finland and found parallels with the establishment of the Turkish Republic. Recognizing Atatürk as a hero and understanding the importance of his reading recommendations, I read this book as a child. That’s how I first learnt about Finland.

That child grew up, and she embarked on her doctoral journey in the country of white lilies. She immersed herself not only in learning Finnish but also teaching Turkish to Finns. Residing in Turku and being Turkish, she is both turkkilainen and Turkulainen. In fact, the connection between Turku and Turkish extends beyond a pun in some languages: In Latvian, “Turku” translates to “Turkish”.

This blog is about my linguistic observations as a teacher of Turkish and a learner of Finnish.

The sounds that we shall not fear

When confronted with words like Lentokonesuihkuturbiinimoottoriapumekaanikkoaliupseerioppilas in Finnish, I remain calm, because for a Turkish native speaker, pronouncing Finnish does not pose a big challenge. Finnish, like Turkish, exhibits a one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds. In my experience of teaching Turkish to Finns, I have observed that the pronunciation of Turkish proves to be similar for Finnish speakers. The phonetic disparities between the two languages are minimal, with, for instance, the /c/ sound in Turkish being pronounced as /dʒ/. I have heard /Selsen/, /Selken/ and /Selchen/ versions of my name from Finnish speakers, each of which I embrace, appreciating the linguistic diversity at play. This linguistic interplay extends to me as well: I find Finnish /ä/ and /r/ a bit challenging. For example, my pronunciation of “Turku” might occasionally be a plain /T-u-r-k-u/ instead of /T-u-rr-k-u/. However, these occasional exceptions in Turkish and Finnish do not change the fundamental phonetic nature of both languages; rather, they contribute to the intrinsic beauty of each.

That word is actually a sentence

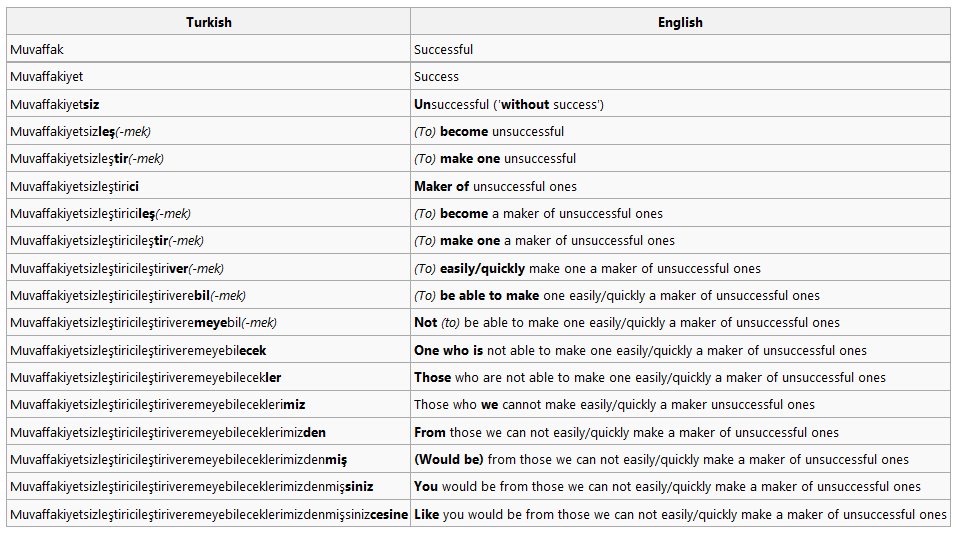

Turkish employs a wide range of suffixes to convey various linguistic elements such as tense, mood, aspect, negation, person, so on and so forth. An extreme illustration of agglutination in Turkish is the sentence muvaffakiyetsizleştiricileştiriveremeyebileceklerimizdenmişsinizcesine, which serves as a notable example of how agglutination functions in the language.

I have not yet presented this example to my Finnish students, not out of concern that it might intimidate them. Finnish speakers have a remarkably open-minded approach and a keen understanding of the agglutination phenomenon, as it aligns with the cognitive patterns ingrained in their native language.

Cases: In that case, there are 14

Both Turkish and Finnish incorporate case systems, but when it comes to cases, I venture to assert that Finns learning Turkish may find themselves somewhat more fortunate than Turks learning Finnish. While Turkish features a more streamlined set of six cases – nominative, accusative, dative, locative, ablative and genitive – Finnish, having 14 cases, poses a greater challenge due to its extensive list including inessive, elative, illative, adessive, allative, essive, translative, abessive and comitative. But despite the complexity, I personally embrace the Finnish cases, seeing them as valuable mental exercises rather than obstacles.

Order flexible word

Turkish and Finnish do not have the same word order. Turkish follows a subject-object-verb order while Finnish employs subject-verb-object structure. Despite this difference, both languages allow for flexible word orders due to the presence of cases. Take the sentence “Atatürk Fin tarihini incelemiştir” “Atatürk opiskeli Suomen historiaa”, consisting of a subject, object and verb – this can be expressed in six versions although each would have nuanced meanings.

In Turkish, verbs bear the weight of the entire sentence. In a canonical, word-ordered sentence, comprehension often hinges on reaching the verb at the very end of the sentence. Planning in Turkish involves deciding the whole content of the sentence early on, as the verb, positioned at the end, appoints the lexical and grammatical rules to the sentence elements. Finnish places the verb earlier in the sentence, providing more time to plan the remaining components. This aspect of Finnish may prove advantageous for learners of the language, offering an opportunity to strategize case usage and consider factors like k-p-t involvement.

So, which is preferrable: Turkish or Finnish? Personally, I find both languages to be exceptional. I love learning Finnish and teaching Turkish. If you haven’t explored them yet, I encourage you to do so.

You can also have a look at my other blog posts published on blog Student Life at the University of Turku:

- Λanguages with a Дifferent AlΦabet * – It’s not all Greek to me anymore.

- Mama mia, sono in Italia! My EC2U adventur-a at the University of Pavia!

- Learning Finnish as a foreign language – Can it be easier than you think?

The author, Selcen Erten, is a doctoral researcher in Digital Linguistics.