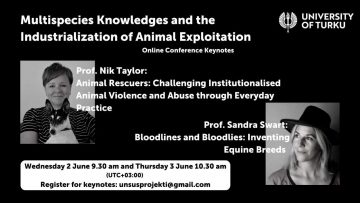

Multispecies Knowledges and the Industrialization of Animal Exploitation

The research project Culture of Unsustainability – Animal Industries and the Exploitation of Animals in Finland since the Late Nineteenth Century (UnSus) arranged an online conference on 2 and 3 June 2021.

The first keynote lecture was Professor Nik Taylor’s Animal Rescuers: Challenging Institutionalized Animal Violence and Abuse through Everyday Practice. Taylor is from University of Canterbury, New Zealand. Taylor asked whose side are we on when we do research. She spoke about vegan-feminist research paradigms. Research should take seriously the fact that the research should be done by, for, and with marginalized groups.

It is about taking in species as a marginalized group, and design research that is inclusive. We must avoid further silencing and invisibilising them. Non-human animals and marginalized groups are not voiceless; they are silenced. Current events, that impact both humans and other species, like the COVID-19 pandemic and the effects of climate change producing a rise in the numbers and severity of environmental disasters make it clear that there is an urgent need to challenge these narratives. One of these ways is to model alternative non-violent relationships across species. Multi-species relationships, particularly those between humans and those individuals who are normatively considered ‘food products’ have this promise.

Second keynote was Professor Sandra Swart’s lecture Bloodlines and Bloodlies: Inventing Equine Breeds. Swart is from Stellenbosch University, South Africa. In this time of global crisis, with a world on fire in many senses of the word, what can historians do in and about the Anthropocene? Swart asks. A key approach is that we should write “more than human history.”

Animal bodies are sites where human histories are contested and fancies and fantasies are enacted. Horse bodies changed and were changed by their move to Africa and the great equine experiment on the continent. The world of animal breeders has sustained, until late into the twentieth century, some of the most antiquated ideas like telegony where foals, calves, and puppies and human babies were considered forever stained by their mother’s original sin of carnal categorical crossing. A key point is that discourses of breeding were not hermetically sealed away from political discourses. Breeding debates, in both state and popular milieu, drew on ideas about race, class and gender.

In addition to keynotes, we had five panels with 17 papers. Many interesting papers delt with animal husbandry, meat propaganda, milk consumption, conceptions of broiler industry and perceptions of farmed fish. In fishery science and politics, the fish has been seen as nothing but raw material for societies, devoid of any ethical considerations. The public discussion of the ethical treatment of fish has grown on a global scale during the recent decades. Other discussions in the panels included how care and exploitation intertwine, and how gendered and sexualized issues are connected in animal keeping and breeding practices. Care has become a prominent theoretical framework for understanding human-animal relationships.

Animal agriculture with its history, technology, expansion and practices, is at the same time global and local. For example, modern slaughterhouses were built in France as early as the early 19th century, whereas the same technology came to Finland and South Africa only in the early 20th century. Although Finland was a latecomer in economic modernization, it eagerly participated in transnational networks of animal business and industries.

Food production with non-human animals leads to dire consequences regarding climate crisis, species extinction, and sentient beings’ exploitation. Yet non-human animals continue to be constructed as edible, killable and exploitable. For example, discourses on ethics and sustainability in the organic farming sector are still framed by carnistic norms and practices.

Overall, comparative research is needed, so that we do not explain changes by purely local factors and omit transnational and global processes. One key issue is still the concept of an animal in the first place: how we are speaking, researching, and taking into consideration that there are so many kinds of animals. Fish and insects are more challenging for humans to feel empathy for or to communicate with, and that is why even more – interdisciplinary – research is needed.